Monkey Punch (1937-2019)

April 17, 2019 · 0 comments

Kazuhiko Kato, who died on 11th April, always had the air about him of a man who had won the lottery. Born in Hokkaido in 1937, his knack for cartooning soon caused him to drop out of electrical engineering college and move to Tokyo, where he moonlighted as an artist, at first in the below-the-line world of manga for rental lending libraries. Artistically inspired by the baroque, bawdy style of MAD magazine, he found early work in crime capers and detective stories, including Gun Hustler, The Murderer List, and The Man Without a Shadow. In 1966, a grumpy editor insisted that he take a pseudonym that made him sound more exotically foreign, and Kato reluctantly accepted. He recounted the story in an interview in Dallas in 2003, noting: “The editor said to me – ‘It’s hard to tell whether your art was done by a Japanese or a foreigner, so let’s create a pen-name that is indistinguishable by nationality.’ And after a lot of discussion in the editor’s room, they came up with MONKEY PUNCH.” Which was nicely inconspicuous. It was only a three-month job, and he figured he could drop the name right afterwards.

Kazuhiko Kato, who died on 11th April, always had the air about him of a man who had won the lottery. Born in Hokkaido in 1937, his knack for cartooning soon caused him to drop out of electrical engineering college and move to Tokyo, where he moonlighted as an artist, at first in the below-the-line world of manga for rental lending libraries. Artistically inspired by the baroque, bawdy style of MAD magazine, he found early work in crime capers and detective stories, including Gun Hustler, The Murderer List, and The Man Without a Shadow. In 1966, a grumpy editor insisted that he take a pseudonym that made him sound more exotically foreign, and Kato reluctantly accepted. He recounted the story in an interview in Dallas in 2003, noting: “The editor said to me – ‘It’s hard to tell whether your art was done by a Japanese or a foreigner, so let’s create a pen-name that is indistinguishable by nationality.’ And after a lot of discussion in the editor’s room, they came up with MONKEY PUNCH.” Which was nicely inconspicuous. It was only a three-month job, and he figured he could drop the name right afterwards.

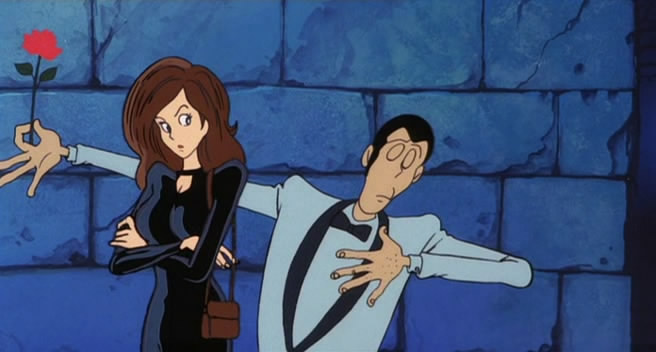

He was, consequently, eternally sorry-not-sorry that his next job would achieve a success so meteoric that he was stuck with the name for the rest of his working life. Lupin III would run in Manga Action magazine for two years, but managed to strike such a powerful note with 1960s readers that it never quite went away. Kato would return to it periodically throughout his career, while animated spin-offs imparted a long, long tail to the franchise that still endures today. Its star was the titular Lupin, supposedly the grandson of the French master-thief created by Maurice Leblanc in 1905, a self-styled Citizen of the World, leader of a rambunctious coterie of criminals: Goemon Ishikawa, namesake of a famous samurai, and Daisuke Jigen, a sharpshooter modelled on Western hero Lee Marvin. They were pursued by the hapless Inspector Zenigata, himself the descendant of a samurai-era folk hero, and alternately helped, hindered or distracted by Fujiko Mine, a buxom burglar conceived originally as little more than set decoration in the style of a Bond girl, but swiftly developed into an independent, sassy accomplice and sometime rival in Lupin’s schemes – manga’s own Emma Peel. “Everybody has an Achilles heel,” commented Jigen in one episode. “Lupin’s just happens to be in his pants.”

It was not always a clean getaway. Copyright law dictated that the Lupin character belonged to the Leblanc estate until 1991, and then after reforms in European law, 2011. Representatives of Leblanc’s heirs complained about the unlicensed use of the character, while lawyers for Kato and his publisher countered that Lupin III was not the original Lupin, by definition. An uneasy stand-off left the name regarded as fair use in Japan but still questionably in copyright elsewhere, causing Lupin to be known as “Rupan” or “Wolf” in some early overseas anime dubs. It is likely that the stink caused by such arguments put paid to a planned French co-production in 1982, the sci-fi spin-off Lupin VIII.

It was not always a clean getaway. Copyright law dictated that the Lupin character belonged to the Leblanc estate until 1991, and then after reforms in European law, 2011. Representatives of Leblanc’s heirs complained about the unlicensed use of the character, while lawyers for Kato and his publisher countered that Lupin III was not the original Lupin, by definition. An uneasy stand-off left the name regarded as fair use in Japan but still questionably in copyright elsewhere, causing Lupin to be known as “Rupan” or “Wolf” in some early overseas anime dubs. It is likely that the stink caused by such arguments put paid to a planned French co-production in 1982, the sci-fi spin-off Lupin VIII.

Regardless, Lupin III enjoyed great success on television and in cinemas in the 1970s, most notably in 1979 with The Castle of Cagliostro, a crime caper helmed by first-time anime feature director Hayao Miyazaki. The character would continue to crop up in movies and TV specials thereafter, imparting a long, long tail to the job that Kato had previously expected to be over by spring 1968. Fifty years on, having largely retired from manga creation, Kato found himself directing “Is Lupin Still Burning”, an anniversary special, while Lupin III continued in his own magazine with sequels by other hands, including Aya Okada’s Inspector Zenigata, a manga series that ran for much of the noughties. Fujiko Mine herself got her own anime series, The Woman Called Fujiko Mine, and the Lupin TV series continued from strength to strength.

It might be said that Lupin’s greatest heist was Kazuhiko Kato’s career, which was largely taken out of his hands in the 1960s and never quite restored to him. Kato made several attempts to write other stories, but none achieved quite the success of Lupin III, which deftly and unsurpassably married Kato’s interests in espionage, crime, and slipstream sf. His other works are hence liable to be ever considered as also-rans. Cinderella Boy, for example, was set in a near-future outlaw metropolis, married the Lupin-Fujiko archetypes at a molecular level, featuring a down-at-heel detective who is forced to share the body of a society femme-fatale. Like a sci-fi detective version of Your Name, they switch each night, each attempting to solve the mystery in their own way – the story was first published in 1980 and turned into an anime in 2003, but few have heard of it. Neither have many of his fans had much of an encounter with the likes of Western Samurai (1968), I am Casanova (1974), or Robot Baseball Team Galacters (1986). Kato, however, never seemed to mind.

“These days the old comics are all released in compilations,” he commented once to Go Nagai. “I stumble across old ones I’ve forgotten and think: ‘Wow, I drew this!?’ I think my art was more alive back then. Fresher, or something.”

Leave a Reply