Music: The AIUEO Song

May 6, 2021 · 1 comment

By Jonathan Clements.

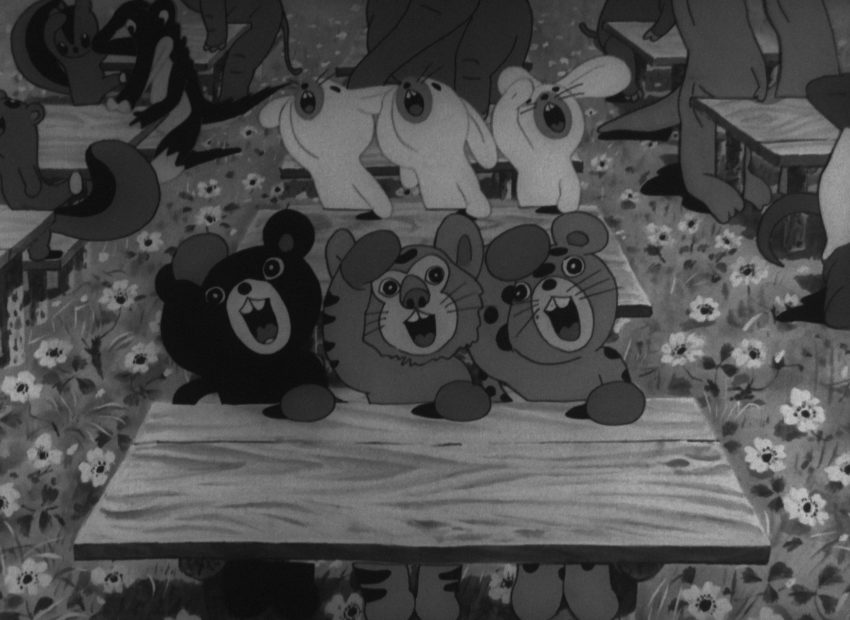

In one of the most widely discussed scenes in Mitsuyo Seo’s 1945 animated feature Momotaro, Sacred Sailors, the frenzied activity of building a South-Sea military base grinds to a halt for the animal soldiers to teach Japanese to the natives. An unruly outdoor classroom of apes, tigers and even a somewhat out-of-place kangaroo, assembles when Wankichi the military dog blows his whistle and begins to teach them the Japanese katakana syllabary with its opening symbol.

A. A, in Japanese, is for atama (head). A is for ashi (foot). A is for asahi (rising sun).

The animals, however, are rowdy and unresponsive, until a bear arrives with a harmonica, allowing Harukichi the monkey to lead them all in a song that derives its lyrics and refrain from the recitation of the Japanese alphabet. The story behind that song, however, is only now coming to light, thanks in part to a recent book chapter by Takashi Kayama from Senshu University in Tokyo.

“The AIUEO Song” is one of the most remembered parts of Sacred Sailors, not the least for Japanese audiences, since they “already know” the lyrics, making it easier to commit to memory. It is an oddly charming moment in the middle of the film, and made enough of an impression on the young Osamu Tezuka that he would tip his hat to it twenty years later with the animals of the jungle in Kimba the White Lion exhorted to learn the “AIUEO Mambo.” But the catchy tune was not written specifically for Sacred Sailors. It was discovered by Seo while watching a newsreel about outreach projects in the Japanese empire. “Apparently the song was sung in a pacification film shown [in China and the South Seas] and became popular,” he said. “It was only for pacification purposes, so had never been screened in Japan, and nobody had seen it here.”

“Pacification” units were embedded throughout the Japanese empire, and were tasked with maintaining order through education: “stabilising the minds” of new subjects, purging anti-Japanese thought, cultural reconstruction and governmental collaboration. The Office of Pacification was intended as the permanent and enduring occupation force, persisting long after the troops had moved on, continuing the conquest of new territories in a subtler and more invasive way, until the territories in question regarded themselves part of one unified Co-Prosperity Sphere. As with the activities shown in the classroom scene in Sacred Sailors, the Office of Pacification was deeply invested in winning the hearts and minds of subject peoples, even to the extent of teaching them Japanese, all the better to encourage its use as a Pan-Asian common language.

But Seo mis-spoke when he said that nobody in Japan knew of the song. Plenty of people had heard it, in much the same way as he had, since footage of it was screened in Japanese cinemas as part of Nihon News, reporting on the adoption of a Japanese curriculum in the newly conquered Singapore.

This tallies with the progress of the Japanese occupation of Singapore, which advanced from the defeat of the British defenders in February 1942, a massacre of thousands of local Chinese that extended into March, and the announcement in April that Japanese would become the medium of education in local schools. By June, Singaporean children were reportedly being made to sing the Japanese classic “Sakura”, but also something referred to as “the AIUEO Song, composed by the Japanese Navy band.” For readers back in Japan curious about the song, the Yomiuri Shinbun even printed the sheet music in the newspaper edition published on 19th August. The use of the song was reported on the Japanese radio, and by the autumn of that year, efforts were made to record it properly, using a children’s choir in September 1942 at Tamagawa Academy in Machida, west Tokyo.

It’s this version of the song, with Tamagawa schoolchildren singing along with their teacher at the piano, that was turned into a one-reel short film, screened in around the Japanese empire with singalong subtitles and a sophisticated bouncing-ball effect. Such graphic overlays were usually the responsibility of animators, although it is not clear which company performed that task here. It can’t have been Seo himself, or he would have surely mentioned it. According to surviving cinema records, the full song, with its sing-along subtitles was, at the very least, screened in cinemas between 1943 and 1945 in Bandung, Surabaya, Jakarta, Yogyakarta, Semarang and Surakarta – all in what is now Indonesia, as well as in Manila and Davao in the Philippines. Looking at the dates, only two of which match, it seems that there may have only been one, or at most two prints of the film, transported from town to town as part of a rotating cinema repertoire.

“The AIUEO Song” was one of several films screened in the Japanese empire to teach the Japanese writing system to schoolchildren, released close behind the tunes “Flower of Patriotism” and “Our Unity” – there are accounts of all three being screened repeatedly. Digging around in the archives, Takashi Kayama has uncovered another version of the song, released on vinyl by Nippon Columbia in November 1942, and recorded by schoolchildren in Singapore, seemingly native Chinese speakers struggling to get the sounds exactly right.

However, it was not heard of again for decades after 1945. Much of the propaganda and pacification materials from the war were destroyed, both by the Allied victors and by Japanese studios trying to hide evidence – propaganda counted as “incitement to war”, which turned anyone who had worked on it into a prospective Class-A war criminal. It was in fact, on the banks of the Tama River, not far from Tamagawa Academy, that the US Occupation forces lit massive bonfires of films and newsreels in April 1946, in an attempt to purge propaganda materials from history. Momotaro, Sacred Sailors itself was thought to have been one of the casualties, believed lost in the purges until reels were uncovered in a Tokyo warehouse in 1983. All extant editions of the film, including the modern Blu-ray release, derive from that one surviving copy.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History.

Cire

September 30, 2023 2:25 pm

Sharing this link has introduced me to a captivating piece of musical history, which has been both informative and entertaining. Thank you for connecting me with this article, which has deepened my appreciation for the cultural significance of music.