Natsuzora

June 13, 2019 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

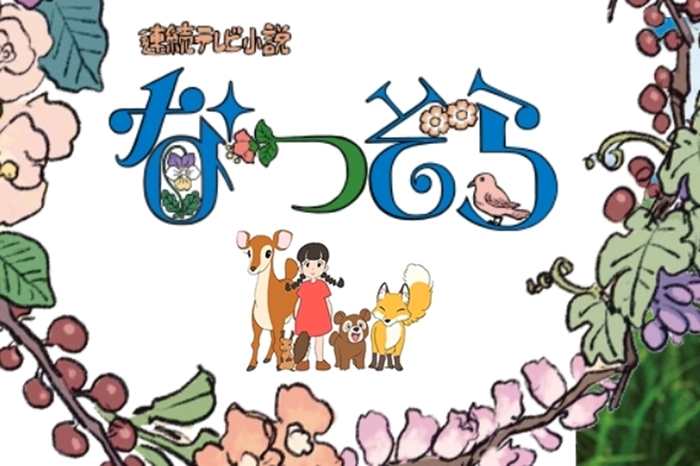

Natsu Okuhara is an orphan girl raised on a dairy farm in the Hokkaido countryside. She overcomes loneliness and adversity, eventually gaining acceptance with her adoptive family, before deciding to set out into the big wide world to seek her fortune. Which is all par for the course in an NHK morning drama, the latest in a long-running sequence of Japanese daytime-TV serials designed to entertain the housebound and the elderly. Natsuzora, in fact, is the hundredth NHK morning drama to air since 1961’s Daughter and Me, and is distinguished by, among other things, an animated opening credits sequence from Sasayuri and the Toei Animation studio. But why…?

Natsu Okuhara is an orphan girl raised on a dairy farm in the Hokkaido countryside. She overcomes loneliness and adversity, eventually gaining acceptance with her adoptive family, before deciding to set out into the big wide world to seek her fortune. Which is all par for the course in an NHK morning drama, the latest in a long-running sequence of Japanese daytime-TV serials designed to entertain the housebound and the elderly. Natsuzora, in fact, is the hundredth NHK morning drama to air since 1961’s Daughter and Me, and is distinguished by, among other things, an animated opening credits sequence from Sasayuri and the Toei Animation studio. But why…?

NHK morning dramas are famous for their educational, affirmative template. There’s nothing unusual about a show that features a plucky country girl making it in the big city during an important transitional time, highlighting a rural destination and a cottage industry into the bargain. What makes Natsuzora different is its blatant otaku-baiting. It takes nearly three months for the daily weekday show to get Natsu out of the countryside and off to Tokyo to seek her fortune. But what a fortune, because she has developed a love of cartoons after seeing Fantasia, and finds herself working as one of the low-ranking animators at “Toyo”, a company that is determined to make Japan’s answer to a Disney movie.

Natsu’s story is based directly on that of the real-life animator Reiko Okuyama (1936-2007), and the colourful characters she runs into at “Toyo” Animation are all caricatures of figures from anime history. “Toyo” of course, is a stand-in for Toei Animation, and its “Hakujahime” project is intended to refer to Hakujaden – White Snake Enchantress – the first colour animated feature made in Japan by the cantankerous producer and “King Hippo” Hiroshi Okawa. Okawa is renamed “Osugi” in this fictionalised account, but as pointed out in a recent article on the Ghibli no Sekai fan site, he is but one of a whole slew of anime celebrities whose salad days are currently being re-enacted for a daytime television audience.

Natsu gets to see the greats of Japanese animation as they fight their way out of poverty and indifference – early Tokyo sequences include her shocked discovery of a colleague moonlighting as a sandwich-board man to pay the bills. She has to deal with harsh taskmasters like “Mr Idohara” (based on the key animator Akira Daikuhara) and “Mr Shimoyama” (based on Yasuo Otsuka), and the scowling genius “Tsutomu Naka” (based on Yasuji Mori). And then there are the young geniuses, the troubled director-to-be Kazuhisa Sakaba (based on Isao Takahata) and his angry-young-man protégé Koya Kamiji (based on the one and only Hayao Miyazaki).

Natsu gets to see the greats of Japanese animation as they fight their way out of poverty and indifference – early Tokyo sequences include her shocked discovery of a colleague moonlighting as a sandwich-board man to pay the bills. She has to deal with harsh taskmasters like “Mr Idohara” (based on the key animator Akira Daikuhara) and “Mr Shimoyama” (based on Yasuo Otsuka), and the scowling genius “Tsutomu Naka” (based on Yasuji Mori). And then there are the young geniuses, the troubled director-to-be Kazuhisa Sakaba (based on Isao Takahata) and his angry-young-man protégé Koya Kamiji (based on the one and only Hayao Miyazaki).

As Natsu learns on the job at Toyo, long sequences of Natsuzora demonstrate the nuts and bolts of working in animation studio. But it remains to be seen just how true-to-life Natsuzora will be in its depiction of this seminal period in the formation of anime. Spoilers for those who don’t already know the history of Japanese animation: feature animation would struggle against the newer, cheaper, “limited” animation being created for television in the 1960s, and the studio that made White Snake Enchantress would become the centre of a bitter labour dispute that led to lock-outs and purges.

The focus on women’s stories common to the NHK dramas means that a number of unsung animation heroines are also getting their due. Kazuko Nakamura, who would go on to become a mainstay at Tezuka Pro on Astro Boy and Ribbon Knight, appears here under the pseudonym “Asako Ozawa”. Akemi Ota, the animator who would give up a promising career to become Mrs Hayao Miyazaki, appears here as “Akane Mimura”. Michio Yasuda, the colorist who would become an integral component of the success of Studio Ghibli, is depicted onscreen as “Momoyo Morita”.

If the life of the real-world Reiko Okuyama is anything to go by, there should be plenty of melodramatic situations ahead. Okuyama married Yoichi Kotabe, one of her fellow animators, and would become the first woman in the animation business to test its policies on maternity leave and returning to work after childbirth. Both she and Kotabe would end up pushed out of Toei by their treatment, and after the 1970s, she moved into children’s book illustration and teaching at the Tokyo Design Academy. Her husband would go on to become a character designer on Heidi: Girl of the Alps, a TV series that would help to assemble the team that would eventually turn into Studio Ghibli. He is credited with offering “period assistance” here in the title animation that celebrates the life of his late wife, and her role in creating Japanese animation as we know it.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History. Natsuzora is currently broadcasting on NHK in Japan, and will hopefully be available with English subtitles soon.

Leave a Reply