Plan 75

May 11, 2023 · 0 comments

by Jeremy Clarke.

Chie Hayakawa‘s dystopian drama Plan 75 examines some of the social fallout of a government policy whereby Japanese people can voluntarily have themselves terminated after age 75.

Sedate classical piano music plays on the soundtrack. The out of focus image could be looking down a corridor. After a long wait, a man in a T-shirt and jeans walks, in focus, into picture foreground. There appears to be blood on his arm and he is carrying a shotgun. Ahead of him, as it now comes into focus, the corridor floor is sparsely scattered with objects: a cup and a bowl, an old person’s walking stick with four legs, something else which we can’t quite make out. He washes at the sink. Another corridor – a fallen walking stick, a pair of slippers, an abandoned bathrobe or perhaps a towel, a collapsed, half-folded wheelchair, wheel still spinning. T-shirt and jeans with shotgun descends the stairs. After a contentious voice-over, T-shirt and jeans waits a long while, then points the barrel of the shotgun at his head and uses his feet to pull the trigger.

A contentious, heartfelt, male voice-over says: “The surplus of seniors is draining Japan’s economy and taking a heavy toll on the young generation. Surely the elderly don’t wish to be a blight on our lives. The Japanese have a long history of sacrificing themselves to benefit the country. I pray that my sacrificial act will trigger discussion and a future that’s brighter for this nation.”

Leaving aside the fact that all this could have been accomplished on screen with far more precision and economy in around a third of the time – something which incidentally could be said of the whole two-hour film, which bulks out Hayakawa’s original 2018 short of the same name, made as part of the Ten Years: Japan anthology – this so-called ‘sacrificial act’ means not so much an act of sacrifice, but an act in which the perpetrator sacrifices not only himself but also a victim or victims. We never find out any more about either, this scene is presumably supposed to resonate with a piece of news announced over the TV or radio: today the government passed the Plan 75 bill, giving the right for assisted suicide to all citizens aged 75 and over. Hate crimes against the elderly are mentioned. (Ah, so that’s what’s been going on.) This unprecedented solution to Japan’s ageing population problem has captured the world’s attention.

This new, live-action feature is a far cry from Katsuhiro Otomo’s script for the anime Roujin Z (1991) which likewise tackled the problem of a growing elderly population, but with far more economy, even if its fetishisation of a pretty, young female nurse looks distinctly dodgy today. Roujin Z posited a machine that would take care of an old person’s every physical and mental need, thereby removing from the younger generation any responsibility of caring for their elders. But Haruko, the nurse at the centre of the story, flies in the face of this attitude: a good person who wants to do the right thing by any patient in her care. When she gets an elderly, hospitalised hacker to enter the personality of her patient’s late wife into his caring machine, it goes on the rampage in an attempt to take “her husband” to the beach.

Plan 75, by way of contrast, is a live action, dystopian drama in which the dystopia looks pretty much like present day Japan, but with the Plan 75 bill enshrined in law. The scene-setting opening massacre notwithstanding, it follows three main characters whose paths will eventually cross. One of four elderly women working as hotel chambermaids is Michi (Weathering with You‘s Chieko Baisho), curiously not named until the four of them are involuntarily retired from work some way into the film; they soon get together to compare notes and check out Plan 75 brochures.

Michi’s daughter hasn’t kept in contact, so the old lady has never seen her grandchildren. She keeps in touch with her best friend from work, fellow former chambermaid Ineko (Hisako Okata), until one day she visits the latter and finds her dead of natural causes. From this point on, Michi is essentially alone.

Finding employment at age 78 proves a near-insurmountable problem. Eventually, all she can get is night shifts directing traffic, which seems highly unsuitable work for someone that age.

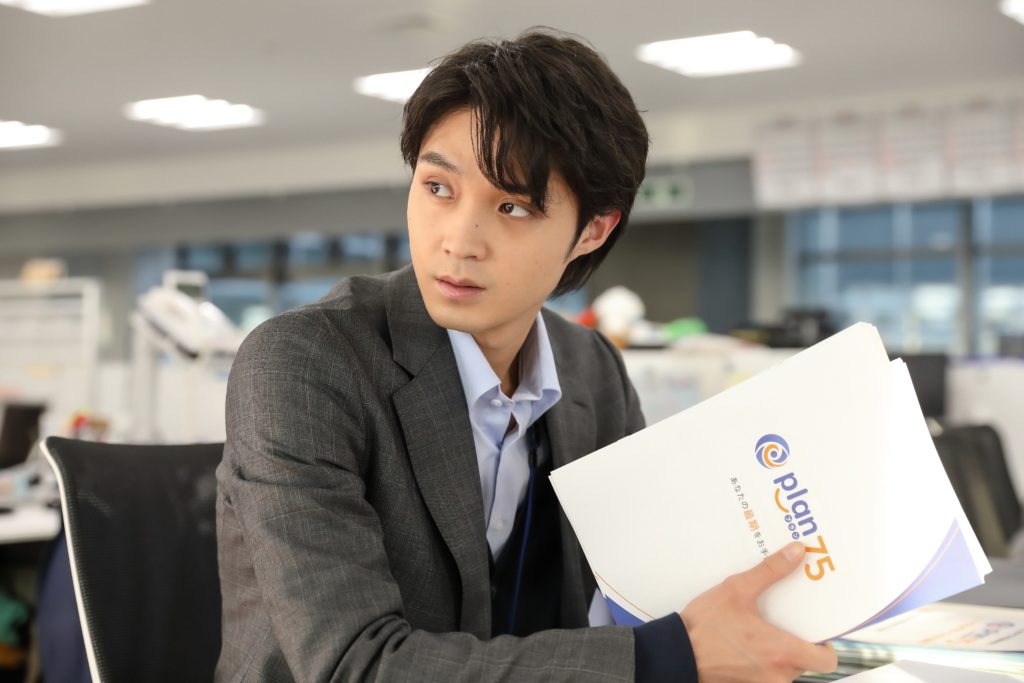

With nothing left to live for, ending her life seems as good an option as any. Signing up for Plan 75 comes with a $1 000 cash bonus (the English subtitles use dollars rather than yen) which she doesn’t know what to do with. You can do what you like with it, she’s told when initially interviewed by helpful Plan 75 employee Hiromu (Hayato Isomura).

Such encounters as performed in the film are very Japanese: people trying hard to be polite to and please one another and being terribly apologetic. In this instance, that hides the fact that the State is basically asking old people to kill themselves, and old people, perhaps out of a desire not to be a burden on the younger generation or the wider Japanese society, are going along with it. (This is very different from Roujin Z, where a small group of old men are fixated on sex and unattainable young nurses, and react to the government programme of robot carers by one of their number enthusiastically hacking into one such robot to render far more humane its pre-programmed agenda to care for its old aged client).

Hiromu is the narrative’s second major character. He later finds himself interviewing the uncle he’s not seen for 20 years and who failed to attend Hiromu’s father’s funeral. Plan 75 has protocols in place for such things, and the uncle is transferred to one of Hiromu’s co-workers. The guilt-ridden Hiromu nevertheless attempts to get to know his uncle better, visiting him at home and ultimately driving him to the facility where, in the next cubicle over from Michi, he is to voluntarily terminate his life.

In a rare, truly touching moment within a film where for the most part everything takes a ridiculously drawn out amount of time to happen, Michi lies on the termination facility bed with medicine being dispensed through a breathing apparatus. The young nurse attending her has a phone conversation about, “maybe it’s broken down – I’ll come over there now.” Suddenly, Michi is alone and anxious. On her right, in the next cubicle, she sees Hiromu’s uncle (who she’s never seen before) also receiving the medicine through a mask. Perhaps there might have been a connection there, but it’s too late for either of them now. Or so it seems. The set-up inadvertently recalls one of the stories in Kenshi Hirokane’s manga Shooting Stars in the Twilight, in which two old people volunteering for euthanasia instead strike up a last-minute friendship.

The third major character is is Maria (Melancholic’s Stefanie Arianne), a Filipino Christian working in Japan while her family remains back in the Philippines. She is facing financial hardship on account of the impending hospital operation her five-year-old daughter needs. A friend at her house church puts her on to a more lucrative job working for Plan 75, removing personal effects from corpses. Her male co-worker shows her unexpected benefits: the dead don’t take anything with them, and all their items go to landfill, so she might as well take anything she finds that she likes. This could include money, if the corpses have it on their person. For example, we see him taking a pair of old spectacles better than the ones he currently wears, and putting his old ones in the tray of the deceased’s possessions. She grapples briefly with the morality of this – we can see it going through her mind – is it a form of stealing? – but swiftly realises he is right and adapts to the idea.

Towards the end, she is on her shift when a distraught Hiromu turns up hoping he’s not to too late to save his uncle, so she comes to his aid.

One minor character is worth a mention. Michi is assigned Plan 75 phone operative Yoko Narimiya (Yumi Kawai) in the run-up to her voluntary termination, with whom she gets a paltry 15 minutes per call. Michi pours out her heart to Yoko, who breaks protocol by agreeing to meet with her. It’s okay as long as no-one finds out, says Yoko, and in this instance no-one ever does. Michi voluntarily gives Yoko some of her $1 000 cash grant since she doesn’t know what else to do with it. On their final phone call, Michi pours out her heart to Yoko in gratitude for everything she has done for her, only for Yoko to give a terse, bureaucratic, scripted farewell that breaks Michi’s heart in a matter of seconds.

Alongside Yoko, we later overhear a group of newly recruited Plan 75 workers being told that the purpose of their phone calls is to help their clients go through with the termination, rather than pulling out as they are legally allowed to at any point – a chilling if utterly believable revelation.

Despite such occasional flashes of brilliance, Plan 75 is not a great film. It walks through rather than gets to grips with the issue of voluntary euthanasia – for that, you’d be better off seeing last year’s French drama Everything Went Fine. It’s not really provocative sci-fi dealing with the problem of the social burden of an ageing population like Roujin Z or (although it deals with other things too) Hollywood’s Soylent Green (1973). However, it does provide a terrifying glimpse into a Japanese view of that issue which suggests that it might not be the best country in the world in which to grow old and die.

Plan 75 is released in the UK and Ireland on 12th May 2023.

Jeremy Clarke’s website is jeremycprocessing.com

Leave a Reply