Ronja the Robber’s Daughter

December 4, 2017 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

Recently, I wrote a mildly provocative piece suggesting that Ghibli’s acclaimed, proudly old-fashioned filmmaking might be commercially outmoded by slicker crowd-pleasers like Your Name. In the piece, I touched on Ghibli’s roots in 1970s anime, and mentioned an institution called World Masterpiece Theatre (WMT for short).

Recently, I wrote a mildly provocative piece suggesting that Ghibli’s acclaimed, proudly old-fashioned filmmaking might be commercially outmoded by slicker crowd-pleasers like Your Name. In the piece, I touched on Ghibli’s roots in 1970s anime, and mentioned an institution called World Masterpiece Theatre (WMT for short).

A new home release, Ronja the Robber’s Daughter, is a good reason to look deeper into this history. For Ronja is both a Ghibli production – at least everyone says it is – and a heartfelt throwback to the WMT tradition. We’ll explain what WMT is below, but let’s start with Ronja.

It’s a 26-part TV serial released by Studio Canal on Blu-ray and DVD. Some readers may have seen it already, as it’s been available on Amazon Prime. Like many Ghibli films, it’s the story of a plucky little girl. Ronja is indeed a bandit’s daughter, in a castle in a forest in a fantasy Sweden, where harpies soar and muttering “grey dwarves” skulk.

In one of the most vivid sequences, Ronja’s playing in the snow when she gets her foot stuck in a hole and used as a cradle-rocker by underground critters called “Rhumphobs”. Listen closely to the male, voiced in the English dub by a long-time anime and Ghibli fan called Jonathan Ross. But Ronja’s main story is a junior Romeo and Juliet, as Ronja secretly befriends a boy from a rival clan.

The first thing everyone will notice is that Ronja is – horrors! – in CG. To judge by online comments, Ronja’s look has put off many anime fans. But the actual series is far better than the trailer suggests, with animation that only improves. The fantasy creatures are wonderful, but the humans are the real achievement. Their designs look inevitably synthetic, but their movements and faces are expressive and nuanced.

That said, it’s not Ghibli animation. “Animation Production” was by Polygon – the studio behind Sidonia, Blame! and the new horror-thriller Ajin: Demi-Human. (I wrote about Polygon’s early history here.) Ghibli has a “Cooperation” credit, suggesting its contributions were advisory and/or financial. You could see Ronja as a “pseudo-Ghibli” animation like The Red Turtle, which we’ve discussed at length.

That said, it’s not Ghibli animation. “Animation Production” was by Polygon – the studio behind Sidonia, Blame! and the new horror-thriller Ajin: Demi-Human. (I wrote about Polygon’s early history here.) Ghibli has a “Cooperation” credit, suggesting its contributions were advisory and/or financial. You could see Ronja as a “pseudo-Ghibli” animation like The Red Turtle, which we’ve discussed at length.

But that’s a harsh view of it. Ronja feels far more like what people think of as Ghibli than Turtle, from the moment little Ronja first scampers into the wood, yelling greetings at trees and animals. As well as narration by Gillian Anderson, who was in the dubs of Princess Mononoke and Poppy Hill, Ronja has character designs by Katsuya Kondo, a vastly experienced Ghibli artist, who designed the characters in Ponyo and Kiki.

Like Ronja’s look, its director may put off some fans. It’s Goro Miyazaki, director of the despised Tales from Earthsea, with a reputation in some circles as anime’s Jaden Smith (and just announced as the director of a forthcoming Ghibli CG feature). I’ve defended Goro elsewhere; let’s just say Ronja feels entirely different from both Earthsea and Goro’s better-regarded non-fantasy, From Up On Poppy Hill. But there’s still an important link between Ronja and Earthsea.

Goro wrote a blog at the time of Earthsea, translated by Paul Barnier. In it, Goro stressed he saw Earthsea as retro, a stylistic throwback to decades-old anime like the 1968 film The Little Norse Prince “If we look at the work now, it seems simple, but that much more powerful,” he wrote.

Goro continued to extol old anime. “The characters and artwork are not the slightest bit inferior when compared to present day animation. It’s not simply a case of returning to the past, but simple pictures definitely do not mean that reality is lacking.”

Goro’s Ronja is made with similar convictions. For all its Ghibli-ish sensibility, it’s really a throwback to Ghibli’s precursors. This time, Goro wasn’t looking back to Prince, but to a kind of anime that came just afterwards. These were long – often year-long – serials, based on children’s books.

Goro’s Ronja is made with similar convictions. For all its Ghibli-ish sensibility, it’s really a throwback to Ghibli’s precursors. This time, Goro wasn’t looking back to Prince, but to a kind of anime that came just afterwards. These were long – often year-long – serials, based on children’s books.

And not on Japanese books. These were books from around the world, often classics from Britain and America. Yet the anime versions, though beloved in many territories, are practically unknown in Britain and America. How many Anglophone anime fans know there was once an anime of Pollyanna? Little Women? The Swiss Family Robinson?

The seeds for these series included a 1969 anime of Moomin, the Finnish stories of hippo-like creatures by Tove Jansson. An article by Jonathan Clements recounts how the anime’s liberties outraged the author, including a tank drawn by a silly artist called Hayao Miyazaki. Initially, it seems such shows relied heavily on comedy and cartoon business, like Disney cartoons in America. (Think what Rudyard Kipling would have made of Disney’s Jungle Book.)

But things soon evolved. Miyazaki took part in a bid to adapt Sweden’s Pippi Longstocking; you can find the full story here. Also involved was Miyazaki’s close friend Isao Takahata. The bid fell through, because (allegedly) Pippi’s author Astrid Lindgren thought Japanese cartoons were too violent. In 1981, Lindgren wrote Ronja the Robber’s Daughter; she died in 2002, before it was animated by Miyazaki’s son.

From the failed Pippi Longstocking, Takahata and Miyazaki turned to another classic, the Swiss book Heidi by Johanna Spyri. Broadcast in 1974, Heidi was one of the most important anime ever made.

It was far from Disney’s Jungle Book. Heidi’s opening episode begins with languid shots of a charmingly-drawn Swiss village at dawn. Little Heidi is introduced standing in a courtyard, looking anxious. She’s distracted by chickens in a coop for a few moments before grown-ups appear and we learn what’s happening (she’s about to journey into the Alps).

With no dialogue and patches of silence, this opening is extremely prophetic of the Ghibli style. Miyazaki slaved on the show, creating towering heaps of layout drawings, three hundred per week for a year. But Miyazaki himself stressed Heidi was Takahata’s vision. In Starting Point, Miyazaki described it as “everyday-life animation – stories with realistic settings that place importance on everyday matters… [showing] how the main character deals with events that occur in real life.”

Takahata’s Heidi was a ratings hit. Its level of animation quality, with some eight thousand pictures per episode, ran against the cost-cutting measures established by Tezuka in Astro Boy. In his Anime: A History, Jonathan Clements argues the emphasis on quality “was less a new development than a vestigial remnant of the attention to detail practiced in Toei’s cinema animation” – films like Little Norse Prince.

Takahata’s Heidi was a ratings hit. Its level of animation quality, with some eight thousand pictures per episode, ran against the cost-cutting measures established by Tezuka in Astro Boy. In his Anime: A History, Jonathan Clements argues the emphasis on quality “was less a new development than a vestigial remnant of the attention to detail practiced in Toei’s cinema animation” – films like Little Norse Prince.

Heidi led directly to the instigation of a line of similar serials, which would play through the year on Sunday evenings and would be collectively known as World Masterpiece Theatre. Miyazaki and Takahata worked on some of them, though Miyazaki quickly despaired of the grindstone. Takahata directed two more WMT series: Marco (see below) and Anne of Green Gables.

These series would have several things in common. First, they were based on non-Japanese children’s books. They were also set outside Japan, in a wide range of countries. This was a huge part of their appeal, showing children foreign landscapes, foreign architecture, foreign ways of life. The series were also set in pre-TV times, where the only way for a child to find excitement was outdoors, in the world.

Some of the settings anticipated Ghibli. For example, Takahata’s 1976 serial Marco (aka 3,000 Miles in Search of Mother) is the story of an epic journey. Yet it starts with more than a dozen episodes showing the little hero’s urban life in the port city of Genoa, Italy. These episodes feel very like the depiction of the city in Kiki’s Delivery Service.

Marco is especially remembered for its first episode. In the story, the boy’s mother has to travel alone from Italy to Argentina to earn money for her family. A stricken Marco protests; his big brother, also distressed, tries consoling him, but finally hits him instead.

Marco is especially remembered for its first episode. In the story, the boy’s mother has to travel alone from Italy to Argentina to earn money for her family. A stricken Marco protests; his big brother, also distressed, tries consoling him, but finally hits him instead.

At the episode’s end, the mother’s ship leaves. Marco runs along the port wall, screaming for her, until the ship is out of sight. It’s easy to link the scene to Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies a decade later. (In Grave, think of the moment of Setsuko crying for her mother beside the swings).

Moments like Marco’s teary dash mean that WMT is sometimes described as an extremely sad franchise. And it is, at least beside American TV cartoons where even the excellent Avatar: The Last Airbender rarely shows suffering and death directly. Compare that to the cheery Ronja; a clear sign that it’s informed by the WMT style is that it has both. Indeed, the story pivots around an episode where the girl sees how cruel grown-ups can be, including the grown-ups she adores and cherishes.

You can certainly link the sad bits of WMT to weepy anime tragedies like Fireflies, or to take another child-centred example, Giovanni’s Island. But WMT as a whole is no more about sad childhoods than Harry Potter or Totoro. There are countless WMT episodes showing joyful adventures in exciting, beautiful settings, from Heidi’s Alps to the Lake of Shining Waters in Anne of Green Gables.

For readers who remember British children’s TV circa 1980, the WMT serials weren’t so different from the imported live-action serials of the same stories that we saw on BBC; for example, the dub of a Swiss/German Heidi, or the endlessly-repeated Huckleberry Finn and His Friends.

But the Japanese cycle lasted far longer. There were over twenty annual serials in the “official” WMT line, which didn’t include its progenitor Heidi, or similar anime by other companies. Among the latter was a version of Wizard of Oz in the 1980s, which made it to American TV (it’s the one with narration by Margot Kidder). Then there was the 1991 Twins at St. Clare, from Enid Blyton’s school stories, but even Blyton’s name didn’t get it shown in Britain.

Many of these series were shown in Europe. You can buy St. Clare’s boxsets on the French Amazon site, as well as Princess Sarah, a 1985 WMT version of A Little Princess by Frances Hodgson Burnett. (Sadly, the French editions lack English subtitles.) But few of these shows reached Britain; only fantasies like Wizard of Oz and at least one videotape of the WMT Peter Pan. As of writing, the British and American Amazon sites are offering streams of the WMT version of Little Women, apparently dubbed-only; it’s entitled Tales of Little Women and is divided into four twelve-part ‘seasons.’

WMT finally foundered in Japan in the 1990s, though a few more series came out in the 2000s. Yet it’s easy to find later anime shot through with the WMT ethos. It pervades Ghibli, especially the films by Hiromasa Yonebayashi: Arrietty, When Marnie was There and his new non-Ghibli Mary and the Witch’s Flower.

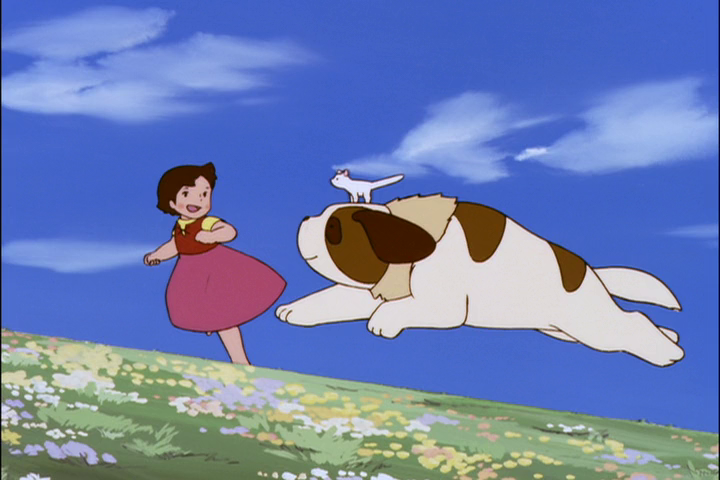

Sunao Katabuchi actually worked on WMT shows like Pollyanna and Little Women. Now he mixes up work on Black Lagoon – which is about as far from WMT as possible – with lyrical celebrations of the childhood “now” in Mai Mai Miracle. (pictured — films like Totoro and Mai Mai Miracle extend the WMT approach to Japan, though always pre-TV Japan.) Another of Katabuchi’s films, Princess Arete, expands a short British children’s book in typically languid WMT style. It’ll have a release by Anime Limited next year.

Sunao Katabuchi actually worked on WMT shows like Pollyanna and Little Women. Now he mixes up work on Black Lagoon – which is about as far from WMT as possible – with lyrical celebrations of the childhood “now” in Mai Mai Miracle. (pictured — films like Totoro and Mai Mai Miracle extend the WMT approach to Japan, though always pre-TV Japan.) Another of Katabuchi’s films, Princess Arete, expands a short British children’s book in typically languid WMT style. It’ll have a release by Anime Limited next year.

But can these anime ever sell? In my previous article, I played devil’s advocate. Yonebayashi’s box-office is far from Ghibli’s peaks. Mai Mai Miracle barely registered in Japanese cinemas. Fast, dense, storytelling in in; languid, silent reflection isn’t ad-friendly. On ANN, Justin Sevakis argues that the WMT tradition was killed by magic girls and Shonen Jump.

But then, who would have thought WMT could have taken off in the late 1960s, in the age of Disney musicals and Speed Racer? And if Enid Blyton and Roald Dahl are still bestsellers in 2017, decades after the authors’ deaths, then who are we to rule out a WMT revival?

Two years ago, France remade Heidi as a CG cartoon, designed very like the 40 year-old Takahata version. The “London Live” cable channel now screens it between Glitter Force (the Americanised PreCure) and Power Rangers. Meanwhile Netflix’s live-action Anne, a new version of Anne of Green Gables, has been hugely praised… though it’s also been criticised for being too dark for children.

Perhaps the time is coming for a new WMT, to strike its own balance, and trust in the power of lovely drawings to offset any amount of dark content. Remember, you can get away with anything in a cartoon, at least a Japanese cartoon.

Ronja the Robber’s Daughter is released in the UK by Studio Canal.

Leave a Reply