Crouching Tiger II: Sword of Destiny

January 17, 2016 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

Jiaolong, (Zhang Ziyi’s character from Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon) has suffered since the events of the movie. Her new-born son is stolen from her and substituted for a baby girl, and she ends up as a wealthy sword-for-hire in the desert city of Dunhuang, guarding Silk Road caravans and raising her adopted daughter, Snow Vase (Natasha Liu Bordizzo). She hangs around long enough to info-dump the plot of the previous movie, and then leaves in search of her long-lost son. Snow Vase sets off herself, on an inexorable collision course with her stepbrother – the titular Iron Knight of the original book, renamed Wei-fang in this novelisation (although online materials for the movie refer to him as Tie-fang… has anyone edited this?).

Jiaolong, (Zhang Ziyi’s character from Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon) has suffered since the events of the movie. Her new-born son is stolen from her and substituted for a baby girl, and she ends up as a wealthy sword-for-hire in the desert city of Dunhuang, guarding Silk Road caravans and raising her adopted daughter, Snow Vase (Natasha Liu Bordizzo). She hangs around long enough to info-dump the plot of the previous movie, and then leaves in search of her long-lost son. Snow Vase sets off herself, on an inexorable collision course with her stepbrother – the titular Iron Knight of the original book, renamed Wei-fang in this novelisation (although online materials for the movie refer to him as Tie-fang… has anyone edited this?).

Not unlike the sprawling Star Wars saga, Wang Dulu’s original series of kung fu novels had a core trilogy to which a tardy prequel and sequel were appended. Iron Knight, Silver Vase (1942) was set 19 years after the events of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (1941). But this is not quite Iron Knight, Silver Vase; the story has taken a convoluted process to the page. This is not a direct translation of Wang Dulu’s somewhat turgid 1942 original, but a novelisation based on a screenplay by Marco Polo’s John Fusco. This is a tough row to hoe, not merely as a sequel set a generation later, but also as a story lacking the break-out star of the original (Zhang Ziyi wouldn’t get out of bed for a director who wasn’t Ang Lee). Meanwhile, the Ang Lee film unhelpfully killed off Li Mubai (Chow Yun-fat), meaning he also had to be written out of this sequel.

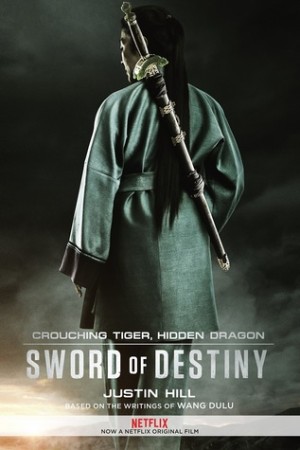

The publicity for it calls it Sword of Destiny, but the cover of the Kindle edition I downloaded calls it The Green Legend. Meanwhile, the sword that everybody is looking for is called the Green Legend in this book, but the Green Destiny in publicity. Yes, it’s confusing… one imagines a pile of multi-coloured papers dumped on the desk of novelist Justin Hill, with a threatening note from Harvey Weinstein and a countdown clock to a close deadline. The acclaimed author of The Drink and Dream Teahouse, which managed to snag the great honour of being banned in China, Hill has a reputation that rests both on delicate China-themed literary fiction and mighty-thewed swashbuckling; and you can see why he was a natural choice. However, much like the confusion over the book’s title, Hill’s place in the continuum of creation is unclear. The differing covers either bill him as the sole author or “based on the writings of Wang Dulu”, the metadata credits him as the author “with Wang Dulu”, and some online publicity credits the book to “Wang Dulu and Justin Hill.”

The publicity for it calls it Sword of Destiny, but the cover of the Kindle edition I downloaded calls it The Green Legend. Meanwhile, the sword that everybody is looking for is called the Green Legend in this book, but the Green Destiny in publicity. Yes, it’s confusing… one imagines a pile of multi-coloured papers dumped on the desk of novelist Justin Hill, with a threatening note from Harvey Weinstein and a countdown clock to a close deadline. The acclaimed author of The Drink and Dream Teahouse, which managed to snag the great honour of being banned in China, Hill has a reputation that rests both on delicate China-themed literary fiction and mighty-thewed swashbuckling; and you can see why he was a natural choice. However, much like the confusion over the book’s title, Hill’s place in the continuum of creation is unclear. The differing covers either bill him as the sole author or “based on the writings of Wang Dulu”, the metadata credits him as the author “with Wang Dulu”, and some online publicity credits the book to “Wang Dulu and Justin Hill.”

A generation after the events of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Shulien (Michelle Yeoh) is in the martial arts equivalent of witness protection, practising her kung fu moves as a secluded hermit, only venturing into town once a month to buy rice and black pudding. True to tradition, she is a superhero on call, “sallying out, if necessary, to fight injustice.” News arrives that her ally Duke Te, the guardian of the fabled sword Green Legend, has died in distant Beijing. Green Legend is a blade with unspecified McGuffin magic properties, a Chinese Excalibur, once wielded by the legendary Guan Yu, a warrior who became a god. So she’d better make sure it’s in a safe place…

Meanwhile (there is a lot of meanwhiling), Jiaolong’s long-lost son Wei-fang (Harry Shum, Jr.) has been raised by his meek adoptive parents, but he voices a desire to study the martial arts instead of the stuffy Confucian curriculum forced upon him. This, comments one character, is as silly an idea as “turning the mighty mountain pine into chopsticks,” and only gets tenser when his stepmother starts talking about setting him up with a nice young bride. Like his birth-mother, Wei-fang would rather be fighting an army. Eventually, he leaves home to go in search of a legendary Twelve-Sided Pagoda where he can learn the way of a warrior.

Meanwhile (there is a lot of meanwhiling), Jiaolong’s long-lost son Wei-fang (Harry Shum, Jr.) has been raised by his meek adoptive parents, but he voices a desire to study the martial arts instead of the stuffy Confucian curriculum forced upon him. This, comments one character, is as silly an idea as “turning the mighty mountain pine into chopsticks,” and only gets tenser when his stepmother starts talking about setting him up with a nice young bride. Like his birth-mother, Wei-fang would rather be fighting an army. Eventually, he leaves home to go in search of a legendary Twelve-Sided Pagoda where he can learn the way of a warrior.

Before long, he’s in the foothills near the fabled Shaolin Temple, where he finds a hermit to train him and a bunch of ruffians to practice on. Everybody and his dog is looking for the Green Legend sword, and soon the characters converge on Beijing. Initially at odds with one another (in fact, initially seeming to occupy three different books), the main cast team up to fight off a greater evil, largely comprising characters and situations returning from Precious Sword, Golden Hairpin (1938), the second book in the series – as-yet untranslated. This pitch-invasion supplies much of the action heavy-hitters in the cast, particularly Donnie Yen and Jason Scott Lee.

Whereas Ang Lee’s 2001 Crouching Tiger movie was deliberately highbrow, (only really regarded as a “martial arts film” by people who had never seen one before), John Fusco’s fingerprints on this sequel display a much more modernist, action-movie sensibility. The story contains several anachronisms and fudges that owe more to the martial arts fictions of the 20th century than the truth of the 19th, but this, too, is in keeping with the tone of Wang Dulu’s originals, which similarly took place in a fantasy dreamtime. It is our modern acquaintance with the word nunchaku that causes it to be wedged into the text here, a century before the Chinese would have ever used it; similarly, a modern understanding of the word wushu informs its habitual use by the characters.

Whereas Ang Lee’s 2001 Crouching Tiger movie was deliberately highbrow, (only really regarded as a “martial arts film” by people who had never seen one before), John Fusco’s fingerprints on this sequel display a much more modernist, action-movie sensibility. The story contains several anachronisms and fudges that owe more to the martial arts fictions of the 20th century than the truth of the 19th, but this, too, is in keeping with the tone of Wang Dulu’s originals, which similarly took place in a fantasy dreamtime. It is our modern acquaintance with the word nunchaku that causes it to be wedged into the text here, a century before the Chinese would have ever used it; similarly, a modern understanding of the word wushu informs its habitual use by the characters.

A martial artist himself, Fusco has an insider’s-eye appreciation of the physicality of fighting. In Ang Lee’s film, the mystic nature of qi caused the characters to float, so tuned with the universe that they appeared to lose their body-mass. In Fusco’s script (or at least, Hill’s novelisation of it), qi is a far more visceral and menacing force. It is introduced in hokey Star Wars terms, when Shulien says: “It is all around us. It is the air we breathe, the will that lifts us from the ground when we are tired, the thing that sparks our life within our mother’s womb…” But in the fight scenes, qi is impressively presented as a primal, explosive power, threatening to overwhelm and rupture its human vessels, welling up to create fighting strength, but bursting into nose-bleeds and impinging on consciousness.

There’s a lot riding on this. The Chinese market, both in the People’s Republic and overseas, is the new hope of the movie industry, and Netflix plainly sees this as a prestige project to get a foot in the door. Even though Wang Dulu gave up writing after the Communists took power in 1949, and was persecuted during the Cultural Revolution, the Hollywood side of production clearly assumes that his name will be a hit with a modern Chinese audience, both in the PRC and in overseas Chinese communities worldwide. The release is a global tent-pole event for Netflix, which is essentially taking on the cinema establishment by offering a straight-to-your-widescreen movie premiere with big-name celebrities. This novelisation is part of that, helping to elevate Green Legend/Sword of Destiny’s media profile from a (possibly) forgettable TV movie to a classy feature event.

Jonathan Clements is the author of A Brief History of the Martial Arts. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon: Sword of Destiny is released worldwide next month, but the novelisation is already on sale.

books, China, cinema, Crouching Tiger, film, Hidden Dragon, Jonathan Clements, Justin Hill, Netflix, Sword of Destiny, Wang Dulu, wuxia

Leave a Reply