Ten Years of Scotland Loves Anime (Part 2)

October 11, 2019 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

After the first five years of festivals, Scotland Loves Anime opened in 2015 with a screening of Attack on Titan so packed that Glasgow required an overflow cinema. SLA risked becoming so successful that it trampled on one of its own stated aims of introducing anime to the public – so many fans were showing up and booking early that screenings often had no space for casual walk-ins. As with previous years, the schedule was crammed with premieres, including Seiji Mizushima’s Expelled from Paradise, in which an agent from an orbital digitally-ingested enclave must slum it on a post-catastrophe Earth in the search for a rogue hacker.

After the first five years of festivals, Scotland Loves Anime opened in 2015 with a screening of Attack on Titan so packed that Glasgow required an overflow cinema. SLA risked becoming so successful that it trampled on one of its own stated aims of introducing anime to the public – so many fans were showing up and booking early that screenings often had no space for casual walk-ins. As with previous years, the schedule was crammed with premieres, including Seiji Mizushima’s Expelled from Paradise, in which an agent from an orbital digitally-ingested enclave must slum it on a post-catastrophe Earth in the search for a rogue hacker.

The sold-out screening of Dragon Ball Z: Resurrection F began with a public reading of the notorious one-star review it received from the Guardian, which likened it to “Kenny G or Preparation H”, and attacked it for its “money-grabbing… gotta-catch-em-all… trading-card-inspired” awfulness. Audience members were invited to pile on the newspaper’s website for a little martial-arts monkey-wrenching.

Prominently featured in festival publicity was Keiichi Hara’s 19th-century slice-of-life Miss Hokusai. The subject matter alone, examining the life of the over-looked daughter of the famous Edo-period print artist, seemed worthy enough to attract plaudits. But as Hara himself confessed in his onstage interview, Miss Hokusai was less of a feminist bio-pic of an obscure artist, and more of an extended homage to the late Hinako Sugiura, the creator whose manga formed the basis for the anime’s script. From the opening sequence, which smacks the audience with a sudden onslaught of heavy-rock guitars in 1814 Edo, Hara’s film offers a very different take on 19th century Japan. As one wag observed, the result was a samurai-era movie that had hardly any samurai in it.

“I wanted to be fresh,” explained Hara during his onstage interview. “Sugiura wrote about the common people; about the townsfolk, artisans and prostitutes. Japanese media is full of depictions of the Edo period, but Sugiura’s manga told me things I had never seen anywhere else.” The character of O-Nai, Hokusai’s blind younger daughter, becomes a point-of-“view” for all the things about samurai-era Japan that modern viewers cannot see by just looking at old prints. The sounds and even smells of Edo are brought to vivid life – the echoes of the water beneath a bridge; the oppressive silence of snow-bound streets; the cries of the pedlars in the streets. Hara’s film takes these haptic elements to such extremes that he even depicts the gritty, squishy realism of stepping in a samurai-era dog turd.

Miss Hokusai was a proven winner with the festival jury, which conferred the coveted Golden Partridge on it with a majority of five to three. Its only real rival, snagging the rest of the votes and the Audience Award, was Shunji Iwai’s The Case of Hana & Alice, shot as-live and then over-drawn to make it look like an anime. This rotoscoping technique is nothing new, and in fact, was the method used by Disney in the landmark Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, but led to heated debates among festival-goers as to whether it qualified for inclusion in an animation festival at all. Regardless of arguments over the visuals, Iwai’s script was undoubtedly the wittiest and most charming on show, depicting two deluded teenagers involved in what they believe to be a murder mystery, but actually bumbling through a series of urban myths, often of their own making.

Miss Hokusai was a proven winner with the festival jury, which conferred the coveted Golden Partridge on it with a majority of five to three. Its only real rival, snagging the rest of the votes and the Audience Award, was Shunji Iwai’s The Case of Hana & Alice, shot as-live and then over-drawn to make it look like an anime. This rotoscoping technique is nothing new, and in fact, was the method used by Disney in the landmark Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, but led to heated debates among festival-goers as to whether it qualified for inclusion in an animation festival at all. Regardless of arguments over the visuals, Iwai’s script was undoubtedly the wittiest and most charming on show, depicting two deluded teenagers involved in what they believe to be a murder mystery, but actually bumbling through a series of urban myths, often of their own making.

Debates over the true nature of animation also surfaced at the Education Day. Jared Taylor from the Edinburgh College of Art became ardently, well, animated on the topic of what is taught in British universities. “There’s a whole world to animation,” he said, “and it’s not just a straight choice of 2D or 3D. There are colleges that switch to 3D just because it’s easier to teach large groups; it’s an industrialisation of the process. There are colleges that just teach 3D on Maya [an animation program widely used in the industry]. That’s not teaching 3D, that’s just teaching Maya. Animation is 2D and 3D, and a whole lot more!”

Audiences were also divided over Ryotaro Makihara’s Empire of Corpses, rushed onto the festival screens a mere nine days after its Japanese premiere. Based on the novel of the same name, left unfinished by Satoshi “Project” Ito at his death in 2009, but subsequently completed by Toh Enjoe, this steampunk epic offered fantastic potential – Dr John Watson, future assistant to the world’s most famous detective, on the trail of Victor Frankenstein’s lost notebooks and clues for technology that can lead to the immortality of the soul. Notably, Empire of Corpses does not scrimp on the “punk”, depicting the world of the 1870s as a horrific, colonialist zombie economy, with Frankenstein’s reanimation technology put to use creating an entire underclass of undead slaves. But some viewers seemed disappointed with a story that did not seem to live up to the premise of its opening scenes. Some have suggested that this was less a problem for the animators than a result of the novel’s tragic genesis, with the original author dying a mere thirty pages into its creation.

The Edinburgh leg of the festival featured 14 of the short films from Studio Khara’s Animator Expo, including the scabrous and salacious “Sex and Violence with Machspeed”, and the charming “I Can Friday By Day”, in which hamsters and gerbils secretly pilot humanoid robots disguised as schoolgirls. The remarkably talkative and engaging Mahiro Maeda was present in person to discuss both his Karel Capek adaptation “Kanon” and his ultra-violent “Hammer Head”, and to describe the genesis of the project in the desire to give animators the chance to stretch their talents and make apprentice pieces with an appreciably higher budget than the average TV show.

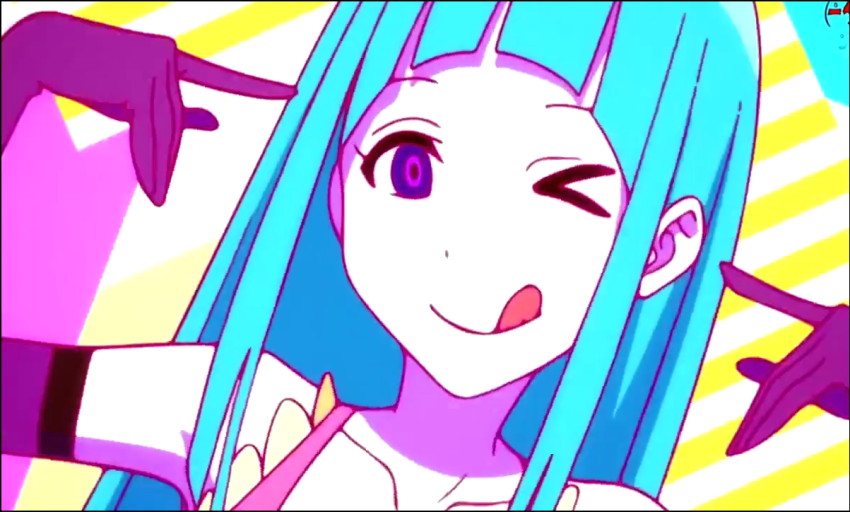

Accompanying Maeda was the young animator Hibiki Yoshizaki, a former compositor and pop video director, whose “Me! Me! Me!” (pictured) has been the most-debated title on fan discussion boards. An initial set-up of jiggling dancing girls transforms into an increasingly erotic, and then horrific series of vivid tableaux, as they turn upon a dreaming and possibly heart-broken boy. Yoshizaki refused to be drawn out on the underlying story of his film, which may, or may not be thematically linked to his other Expo film “Girl”, in which two of the characters are also glimpsed. When quizzed onstage about the film’s origins and intents, he simply paused, downed an entire glass of Scotch, and then said: “Sorry.”

Accompanying Maeda was the young animator Hibiki Yoshizaki, a former compositor and pop video director, whose “Me! Me! Me!” (pictured) has been the most-debated title on fan discussion boards. An initial set-up of jiggling dancing girls transforms into an increasingly erotic, and then horrific series of vivid tableaux, as they turn upon a dreaming and possibly heart-broken boy. Yoshizaki refused to be drawn out on the underlying story of his film, which may, or may not be thematically linked to his other Expo film “Girl”, in which two of the characters are also glimpsed. When quizzed onstage about the film’s origins and intents, he simply paused, downed an entire glass of Scotch, and then said: “Sorry.”

In 2016, one of the festival premieres had taken more than seventy years to make it to the screen. The wartime propaganda film Momotaro: Sacred Sailors had been believed lost until the 1980s, and had only recently been restored in a Blu-ray edition. Now, it finally had its UK premiere, competing rather hopelessly for the Golden Partridge with the super high-budget Final Fantasy: Kingsglaive, and the ultimate winner, Makoto Shinkai’s Your Name. Shinkai’s world-beating feature, fated to become the highest-ever earner at the Japanese box office, only just scraped into the top-slot, in a close-fought jury battle with Naoko Yamada’s A Silent Voice.

Guests included director Yoshimi Itazu, in Glasgow to introduce the UK premiere of his sci-fi short Pigtails, and to gather materials for a secret project that would later be revealed as Welcome to the Ballroom. Unable to explain exactly why, he endured the snickers of the audience when he said he was keen on going to Blackpool to do some research. Producer Kohei Kawase showed up in Edinburgh to talk about his film Accel World: Infinite Burst, and to talk at the Education Day about the logistics of running an anime production, and the perils of trying to please all the fans, all the time.

In 2017, Eureka Seven director Tomoki Kyoda leapt at the chance to introduce his Hi-Evolution 1 (pictured) in Scotland, because for him it was a chance to do a spot of… trainspotting.

“Originally Renton was a place-holder name I just lifted from a film I liked,” he explained, discussing the hero of his film. “I figured I would go back and change it sometime. But then the production got so integrated into rave music, and people kept calling him Renton. In fact, the working title for a long time was Renton 7. Eureka just kind of stuck.

“Originally Renton was a place-holder name I just lifted from a film I liked,” he explained, discussing the hero of his film. “I figured I would go back and change it sometime. But then the production got so integrated into rave music, and people kept calling him Renton. In fact, the working title for a long time was Renton 7. Eureka just kind of stuck.

“The first thing I did when I got to Scotland is I dragged everybody down to Edinburgh. I got them to take my picture as I ran along Princes Street, and down those steps (they’re not where you think they are, you know), and banged into a car. I went and found that bridge from the film. I was like a Trainspotting tourist.”

“Did you find any heroin?” I asked.

“No,” he said.

But the festival’s star turn this year came from producer Masao Maruyama, who regaled audiences at both the Education Day and the festival proper about his career from Astro Boy, through Madhouse, to his latest ventures at MAPPA. In an emotional Q&A that followed a retrospective of Satoshi Kon’s Tokyo Godfathers, Maruyama described his working relationship with the late director.

“I said to Satoshi Kon: I like you. I like your work. There’s greatness in you, but the mainstream just can’t see it. We just don’t get the box office on your films. We did horror with Perfect Blue, we did film history with Millennium Actress. So maybe let’s do something entertaining. And he says: ‘I want to do a thing about three tramps who find an abandoned baby.’ Nobody came to see that one, either.”

“I said to Satoshi Kon: I like you. I like your work. There’s greatness in you, but the mainstream just can’t see it. We just don’t get the box office on your films. We did horror with Perfect Blue, we did film history with Millennium Actress. So maybe let’s do something entertaining. And he says: ‘I want to do a thing about three tramps who find an abandoned baby.’ Nobody came to see that one, either.”

He looked out over the packed cinema at the Edinburgh Filmhouse, and raised a quizzical eyebrow. “What did you think?” The crowd burst into raucous applause and the frail old man beamed with pure joy.

That year’s Golden Partridge was carried away by Masaaki Yuasa’s Little Mermaid pastiche Lu Over the Wall, although the jury was swayed by dissent in the Audience Awards to put some votes behind a film that was not in competition, the same director’s The Night is Short, Walk On Girl, which everybody felt really should have been in the running.

In 2018, Kazuto Nakazawa, director of B the Beginning (pictured), was in Glasgow for his film’s screening, although he very nearly wasn’t, deciding on a whim to run off and buy a scarf, and hence showing up five minutes late for his own Q&A. The son of a kimono-seller, Nakazawa put his childhood observations to use on an anime that specialised in bringing the darkness.

“The motif that really inspired me in this work was the colour black,” he said. “Did you know that the black of a formal kimono is blacker than any other black? Apparently, if you mix all the different colours of dye, black is what you get. I thought it was interesting that black is the sum total of all the different hues, and I had that in mind.”

“The motif that really inspired me in this work was the colour black,” he said. “Did you know that the black of a formal kimono is blacker than any other black? Apparently, if you mix all the different colours of dye, black is what you get. I thought it was interesting that black is the sum total of all the different hues, and I had that in mind.”

Edinburgh’s guest was producer Jack Liang of Polygon Pictures, there to answer questions at the screening of his film Blame!, but also putting in a stint at the Education Day, where he appeared on stage with friend of the festival Hibiki Yoshizaki, back in town on his way to a London exhibition of his Me! Me! Me! art book. None of the guests present this year were representing films in competition, which was probably for the best, since the long-overlooked Mamoru Hosoda was finally in competition with his new film Mirai, which scandalised everybody by failing to win. Even though Mirai would go on to be nominated for an Oscar, it became a football for jury members who figured it didn’t “need” a nod at an anime festival, and that prestige of winning a Golden Partridge was of more use to Hiroyasu Ishida’s debut feature Penguin Highway. Meanwhile, the Audience Award went to Shinichiro Ushijima’s I Want to Eat Your Pancreas, despite a degree of disappointment that the title misrepresented what turned out to be a weepy romance, with no pancreas-eating on show.

And now it’s 2019, the tenth Scotland Loves Anime since Satoshi Nishimura had to be dragged out of a pop-up Halloween candy store, and Andrew Partridge had to go scouring the streets of Glasgow for Irn Bru paraphernalia and tartan souvenirs for the guests. A new jury is convening to watch the films in competition, and a new bunch of people is ignoring this blog until after they’ve got out of the cinema.

And it turns out that the Golden Partridge isn’t gold, or a partridge. It’s a sort of engraved shot-glass, so we really ought to call it the Scotland Loves Anime Glass Glass. I don’t think it will catch on.

Jonathan Clements is the Festival Jury Chairman at Scotland Loves Anime. That’s him with the awesome shirts.

Leave a Reply