The Art of Goro Miyazaki

July 10, 2023 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

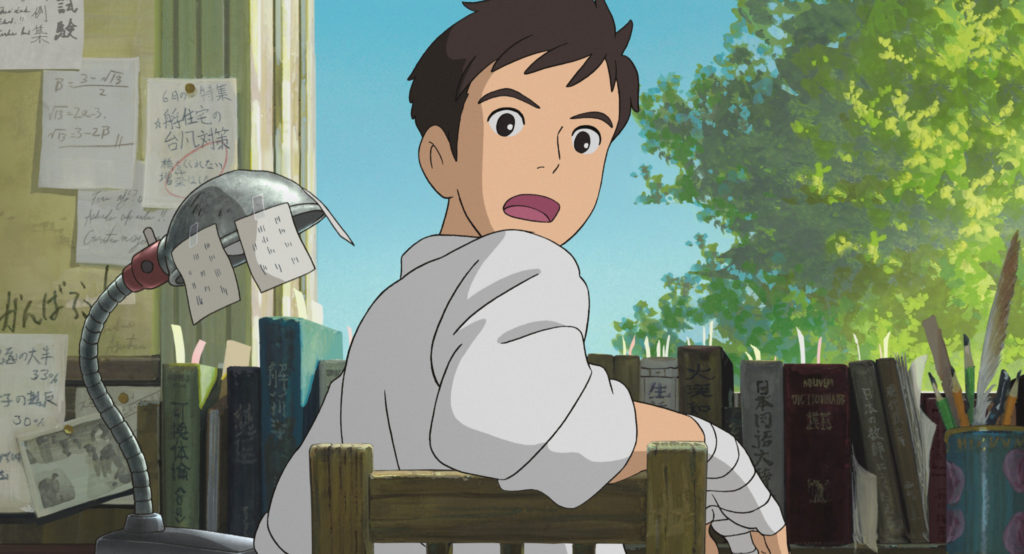

This summer sees the resurgence of Studio Ghibli, as Hayao Miyazaki’s How Do You Live? opens in Japanese cinemas on 14th July. Ghibli articles, understandably, tend to be laudatory verging on hagiographies, running through the studio’s great moments of whimsy and poetry.

But one part of Ghibli’s history gets pundits’ lips curling – the role of Goro Miyazaki. Often he’s not mentioned in Ghibli retrospectives at all, except at the end of “Best to Worst” lists. The communal fan wisdom is he’s not worth talking about, except as a cautionary tale.

I disagree, though I’m resigned to finding little support. However, even if you detest Goro as a director, there are the addictively fascinating meta-texts around him – how he came to be a director, his painful yet touching relationship with his father, his struggles to survive as anime’s best-known nepo-baby. And there are the mysteries around that meta-text, which comes from documentaries and reports authorised by Ghibli itself. It’s a massively compelling story; how far can we trust it?

I first interviewed Goro in 2000. It was in Studio Ghibli, during the production of Spirited Away, but Goro wasn’t involved in anime yet. He’d worked in landscape gardening – he’d designed the rooftop garden of Ghibli’s new studio building. Now he was heading the company managing the upcoming Ghibli museum. Speaking about it, he sounded very like his father.

“Many museums are drawn upon very straight lines,” Goro said. “We wanted the opposite – a building that was exciting and powerful, but also relaxing. It should have a handmade, soft feel, with the floors made of wood and the walls of clay and mortar… There’ll be things for children to touch, examine, feel. We want to bring thoughts and emotions together into one place, into a chaos.” Twenty-three years on, the museum draws hundreds of thousands of guests a year.

In 2006, I interviewed Goro again, at the Venice Film Festival. Now a director, Goro was unambiguous in singling out Ghibli producer Toshio Suzuki as the man who’d manoeuvred him into making Tales from Earthsea, Ghibli’s most despised film. “At the beginning, I was asked to join the group working on the film as an observer,” Goro said. “As the project went along, for some reason I moved into a more central role. Suzuki told me, You know, I don’t think we have any other choice but for you to be the director. He sort of drove the whole thing.”

As his detractors emphasise, Goro was completely new to anime. The obvious inference was that Goro’s elevation to director was a stunt, stretching the established “Miyazaki” brand to a total newcomer. Goro himself talked of making the best of the bizarre situation. “I didn’t know anything!” he told me. “I didn’t know about camerawork, or any of the technical words in film-making. But I am very good at learning through seeing and hearing. So being completely inexperienced, I had the privilege of being able to ask any question, and I used that to the maximum.”

That didn’t stop Goro from being widely seen as Suzuki’s pawn. A former journalist, Suzuki was better versed than most marketers in selling “true-life” stories. So when he allowed media to show shockingly, painfully frank creative conflicts between the beloved director Hayao Miyazaki and his angry, half-estranged son, then it’s hard to separate reality and salesmanship. All that’s clear is that if the conflict was salesmanship, it went badly wrong.

Hayao Miyazaki’s first son, Goro was born in 1967. Hayao seemingly refers to Goro in a conversation about Future Boy Conan, reprinted in the book Starting Point. Hayao mentioned his son was watching Conan’s early episodes, and worried about the fate of the oppressed underground labourers in the background. Although Conan was well into production, Hayao got worried too and rethought the series. He’d envisioned Conan as a love story between children, but in later episodes he shows a full-blown workers’ revolution. That Hayao would take a a script note from the preteen Goro looks ludicrously ironic now.

A snag with this story: Hayao had two sons, and he doesn’t specify which one gave him the comments on Conan. However, Goro was eleven when Conan was broadcast, the ideal age for the show; his brother Keisuke was two years younger.

Goro’s background is vividly retold in the third episode of the NHK documentary, 10 Years with Hayao Miyazaki, on Blu-ray. You might suspect it of being part of the Suzuku-manipulated narrative; it certainly works the audience. The infant Goro’s first word, we’re told, was “daddy.” We’re shown Hayao’s drawings of himself with his tot, and told he had a new motivation as an animator, to make Goro happy.

As Goro entered primary school, Miyazaki grew busier. Even in the 1970s, he was working mammoth stints on Heidi, 3,000 Leagues in Search of Mother and Future Boy Conan. His home time with Goro shrank more and more, as Hayao himself admits on screen. “I owe that little boy an apology.” But, the doc says, there was one way young Goro could “communicate” with his father – by watching his anime. Goro became a massive fan of his dad’s work, even as it took Hayao from him, and stole Goro’s identity too.

“People would always say, Oh, you’re Mr. Miyazaki’s son,” Goro remembers on the documentary. “It was they like they looked me past me to my father. I really hated that.” It’s such a perfect psycho-drama that one can’t help but suspect it. I was reminded of the British film Goodbye Christopher Robin, where a little boy is swallowed up by the globally-beloved fictions created – for him! – by his dad.

What’s especially weird is how this narrative was not just permitted but promoted by Ghibli itself. While Goro was making Tales from Earthsea, he wrote a personal blog on the studio’s site. It’s still available today, in Japanese and in an unofficial translation on Nausicaa.net. In one entry, posted soon before Earthsea’s Japanese release, Goro says Hayao scored full marks as a director, zero as a father.

Interviewing Goro at Venice, I brought up Earthsea’s prelude, in which the boy prince Arren rushes up at his father (who’s depicted as a respected and virtuous king), and stabs him to death. Of course, it was impossible not to ask if the scene – which resembles nothing in the Earthsea books by Ursula Le Guin – reflected Goro’s feelings about his father. Goro’s reply was memorable. “I do not have much relationship with my father; because of that, I have never felt like killing him.”

At this time, Ghibli was esteemed worldwide. It would be one thing if Goro had fallen out with the studio and was speaking in a personal capacity about his discontents. Instead, Ghibli was giving the public ringside seats to a family brawl, involving Japan’s most beloved patriarch having his face scratched by an undutiful son. Just in terms of brand management, it’s boggling.

Surely Ghibli should have been trying to spin a heartwarming story: Hayao as a proud white-haired dad, waving Goro off to Ghibli with a hearty “Ganbatte!” Or at least Ghibli could have given any messy infighting as little attention as possible. It would have made sense if the studio had buried Earthsea in a minimally-promoted release. Instead, foreign hacks like me were interviewing Goro at the Venice Film Festival!

I’ve heard it suggested that the whole dispute was partly or fabricated. It wouldn’t be the first time a film studio had promoted a tasteless parent-child story. But it’s surely not credible the hoax would be spun out so long and pointlessly. The 10 Years documentary was shot years after Earthsea’s release.

Conversely, perhaps Ghibli and specifically Suzuki had an extreme faith that there’s no bad publicity. I remember my surprise that the official, studio-sanctioned Spirited Away “Roman Album” book had an interview with supervising animator Masashi Ando (future co-director of The Deer King), explaining at length why he completely disagreed with Hayao’s portrayal of the heroine Chihiro. Today, you could bring up Ghibli’s recent, arguably reckless decision to not release any trailers for How Do You Live?, nor any details about its story and characters.

Contra false fan claims, Tales from Earthsea was no flop; it made nearly $70 million in Japan. But it was widely panned, “winning” two Japanese critics’ awards for Worst Film and Worst Director. Not everyone hated it. Toshio Suzuki claims in his book Mixing Work With Pleasure that the director Shunji Iwai (The Case of Hana and Alice) “raved” about it. In Britain, the critic Mark Kermode called it “a beautifully realised, full-blooded tale.”

I didn’t go that far myself, but my Sight & Sound review called it “a heroic failure,” dull and misjudged in place, but a “bold and heartfelt” film. On reflection, I think it’s also a fascinating response to Takahata’s 1968 classic The Little Norse Prince, with Arren a male version of that film’s tormented Hilda. It also anticipates another contentious film, Evangelion 3.33, with characters wandering through the ruined scenery of past anime classics.

Earthsea defined Goro’s reputation. Yet his next Ghibli film, From Up on Poppy Hill was far less controversial, especially as Goro made it together “with” Hayao, the film’s writer. Poppy Hill’s production is shown in the 10 Years documentary, depicting another father-son psycho-drama. Goro is shown determinedly going his own way on Poppy Hill, ignoring his dad when he invades the office. Then Goro’s treatment is shredded by Suzuki, who deems the film unreleaseable. Hayao sends Goro a single sketch, showing the main character Umi striding purposefully over a bridge, and that sets Goro on the right track.

Again, the narrative feels suspiciously neat; and that’s not even mentioning how Poppy Hill’s story repeats Tales from Earthsea, as a child loses a father but then metaphorically regains him in the form of a different character. And yet, I still find the notion that all this was fabricated in advance to be even stranger.

Goro went on from Poppy Hill to the TV series Ronja, the Robber’s Daughter, produced by Studio Ghibli but animated by Polygon Pictures. As I’ve discussed elsewhere on this blog, it was a throwback to Japan’s vintage World Masterpiece Theatre anime based on family classics. Ronja itself was based on a book by Sweden’s Astrid Lindgren, who’d once turned down an ambitious anime proposal to adapt her Pippi Longstocking books; a young Hayao was heavily involved in the pitch.

Ronja was made in Polygon’s cel-shaded CG style, which surely put off many Ghibli fans. The series also skewed younger than Ghibli’s films. For the record, I found the heroine Ronja’s face and gestures hugely expressive, and the fantasy creatures excellent. It was the clowning adults who were tedious, and an ending that underwhelmed after an enjoyable journey.

As for Goro’s film Earwig and the Witch, I agree with the majority that it’s a poor film, with a slack, pokey story mostly trapped in a single house. However, I thought Earwig, like Ronja, was again expressive and well-realised, twisting people around her finger not from meanness but out of her own strong sense of self-worth. When Earwig came out, I interviewed Goro once more, this time for NEO magazine. I put it to him that there was a link between the manipulative Earwig and the murderer Arren in Tales from Earthsea.

“That may be true,” Goro said after a pause. “If you have characters that people would expect in an animation, then you would only see very predictable stories. So instead, I’m going away from typical characters, putting in characters that seem like people you would see around you in your daily life – putting elements of these people in a story, which makes the story much more rich, real and relatable.”

As of writing, Goro’s career has seemingly gone full circle. A quarter-century after overseeing the Ghibli museum, he’s involved in the new Ghibli Park near Nagoya. In Goro’s words, “It’s a place where you’re physically able to go into the world of a Ghibli film that you’ve seen.” Today, he faithfully recreates Hayao’s films, even as Earwig suggests he still struggles with his father’s shadow.

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films.

Leave a Reply