The Invisible Man

May 15, 2021 · 0 comments

By Jeremy Clarke.

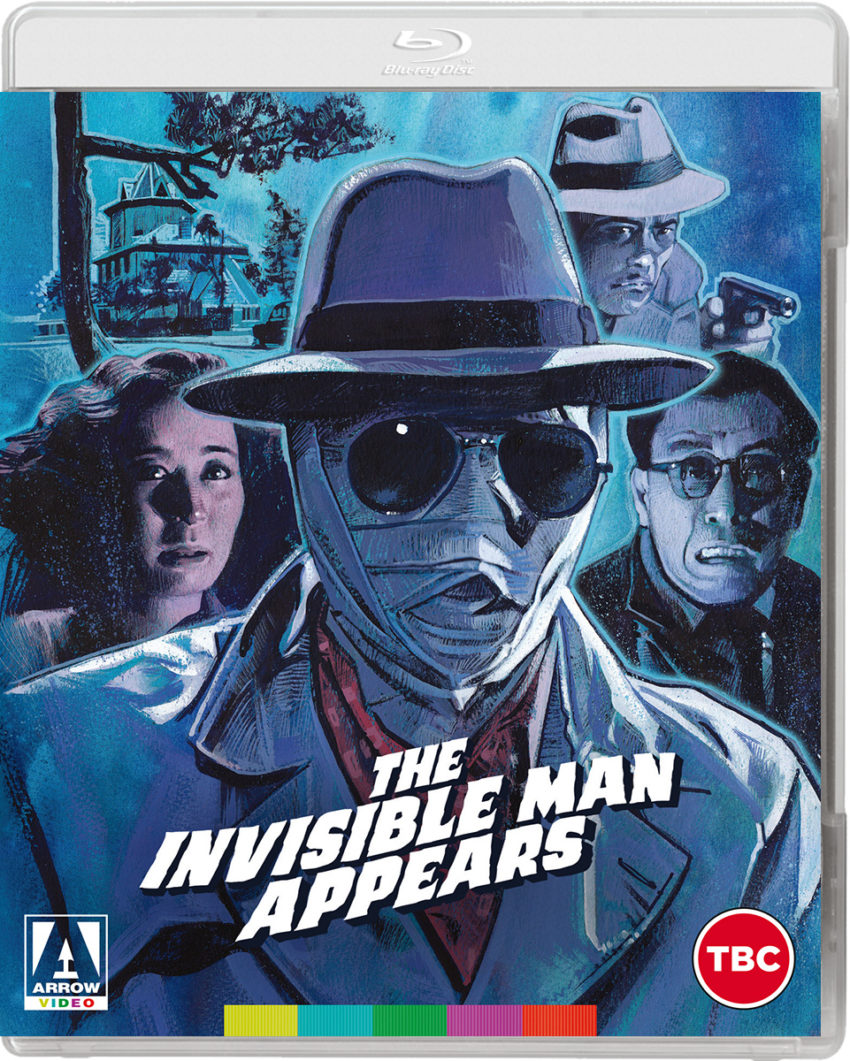

With a title that seems to proclaim, “look at me, I’ve arrived”, Daiei’s The Invisible Man Appears (1949) is a Japanese manifesto, a statement that they can match American movies. Eiji Tsuburaya‘s effects are as good as anything in Universal’s The Invisible Man (1933) and were almost certainly produced at a fraction of the cost.

Although the concept originates with H.G.Wells’ 1897 novel, images from the Universal version starring Claude Rains are lodged in the popular consciousness. Thinking of The Invisible Man, I immediately recall a hat being removed then bandages being unwrapped from covering a man’s head to reveal… nothing… a shirt collar with no neck inside. The Invisible Man Appears recreates such effects convincingly: the removal of clothes by the Invisible Man to reveal nothing visible beneath, so that once undressed he seems to have vanished into thin air. Objects (including a cat!) are carried through the air by an unknown force. A seat cover shows the indentation of the invisible man’s bottom as he sits on it, a cigarette hangs in the air being smoked, a floating gun fires, a motorcycle and sidecar are ridden through the streets without a visible driver.

Tsuburaya had by this point had some 30 years’ experience as a top cameraman, known both for reliability and a penchant for experimentation. He was camera assistant on the seminal horror outing A Page of Madness (1926). He’d been wowed by seeing King Kong (1933) as an adult and had surely seen the Universal monster films including The Invisible Man, so it would have been a point of honour to equal the effects of the original.

The plot is that of a crime movie with various parties chasing after a priceless necklace called the Tears of Amour. An invisible man wears a hat on his head and bandages concealing his face. Quite a few imposters dress similarly so that we don’t know until the bandages are removed whether it’s the real invisible man or not, a repeating red herring with which writer-director Nobuo Adachi has a lot of fun.

Older scientist Dr. Nakazato (Ryunosuke Tsukigata who worked with Kurosawa on Sanshiro Sugata and Uchida on Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji) is researching the possibility of turning things invisible and has promised to marry off his daughter Machiko (Chizuru Kitagawa, also seen in Bloody Spear) to whichever of his two younger assistants Dr. Segi (Daijiro Natsukawa) and Dr. Kurokawa (Kanji Koshiba) can make this work on living human beings. Meanwhile, unscrupulous businessman and potential investor Kawabe (Shosaku Sugiyama) wants the Tears of Amour to impress theatre revue singer and performer Ryuko Mizuki (Takiko Mizunoe), the little sister of Dr. Kurokawa.

As in Daiei’s Warning from Space, Toho’s The H Man and Toho’s Mothra, the theatre revue singer gets her own extended performance sequence, here with a distinct LGBTQ flavour. Attired in a series of men’s costumes, she strums a guitar and sings, dances like a man with other, feminine-attired women, fights as a samurai and finally walks through the middle of a costumed ball which might well be a wedding or a post-wedding ceremony in a toyland-styled, eighteenth century setting dressed in a soldier’s uniform with a girl on her arm.

Mizunoe later jumped studio from Daiei to Nikkatsu to become Japan’s first female producer, her ground-breaking work there including the initial taiyozoku or ‘Sun Tribe’ movie Seasons of the Sun aimed at post-war Japanese youth, and ‘borderless action’ movies modelled on Hollywood film noir, ‘youth gone wild’ movies and French crime pictures. Her last movie at Nikkatsu was the delirious Branded to Kill in 1967, the movie which got Seijun Suzuki fired from the studio. Keith Allison’s essay in the disc’s accompanying booklet (not supplied to journalists by Arrow) reprinted from Diabolique magazine, goes into a lot more detail on her life and career.

Tsuburaya moved over to Toho, where after Godzilla he would work on that studio’s sole Invisible Man film The Invisible Man / The Invisible Avenger (1954). Allison describes it as “cheap and unentertaining”, adding that if Tsuburaya’s effects are sparse, his cinematography showing the mid-century streets of Tokyo’s Ginza is the single element to commend the film.

The lesser of Daiei’s two Invisible Man movies is The Invisible Man vs. The Human Fly (1957). Mitsuo Murayama, working from a script by Hajime Takaiwa, delivers not so much a sequel but, much like the different entries in Universal’s Invisible Man series, a different story with a different set of characters built around the concept. Without Tsuburaya’s guiding hand, the invisibility effects are less memorable but do what they need to. A striking theramin score by Tokujiro Okubo adds an unearthly atmosphere.

This time, the Invisible Man is not a criminal but on the side of the law. It’s a murder mystery with a bizarre twist… Victims are killed in impossible circumstances. A man dies in a cubicle on a passenger aircraft behind a closed door. A woman is killed on an embankment, pointing to a space above her head. A mysterious buzzing sound is heard. An assailant comes out of nowhere to fatally stab people in the back. Further murders take place in a pedestrian tunnel at night and in a lab accessed via its ventilation system.

The ageing Dr. Hayakawa (Shozo Nanbu) tells Chief Inspector Wakabayashi (Yoshiro Kitahara) that invisibility is no longer an impossibility. The doctor’s daughter Akiko (Junko Kano) and his colleague Dr. Tsukioka (Ryuji Shinagawa) are aware of Hayakawa’s research. The Inspector’s investigations lead him to Night Club Asia manager Kuroki (Fujio Harumoto from Giants and Toys) which provides the excuse for the song-and-dance floor show routine, here focusing largely on the singer’s legs. Is singer Mieko (Ikuko Mori) harbouring murder suspect Kusunoki (Ichiro Izawa)? As the body count mounts, links emerge between the victims, many of them having served in the army in the same location during the war. The finale delivers a full-scale manhunt complete with propaganda posters (“Homicidal human fly at large in Tokyo”, “Fear the human fly – you could be next” and “Murderous human fly is trying to kill you.”)

A villainous precursor of Marvel’s Ant-Man (who first appeared in 1962), the Human Fly is realised on-camera by shooting actor Izawa from a great distance so as to appear small, then double-exposed onto whatever else is going on, an effective device thanks to cameraman Hiroshi Murai’s judicious use of light and shade. The actor resembles a fly only in his size – no appendages or features make him look at all like a fly, he just looks like an ordinary human being who is very small, flies and buzzes. One of his most effective appearances has him hover around the scantily clad Mieko as she relaxes in her dressing room.

Beyond the two films and the trailer for The Invisible Man Appears, a helpful Kim Newman interview, Transparent Terrors, furnishes a history of the Invisible Man in the cinema fitting these two films into that. The booklet contains two more essays in addition to Allison’s, one by Windows on Worlds’ Hayley Scanlon about the films’ relationship to the nuclear bomb, science and the American occupation and one by Aardman Animations’ archivist Tom Vincent, placing the films in the dual contexts of the Japanese film industry and the history of special effects in Japan and abroad. Sadly, there are no commentaries.

The Invisible Man double feature: The Invisible Man Appears + The Invisible Man vs. The Human Fly is released in the UK on Arrow Blu-ray.

Jeremy Clarke’s website is jeremycprocessing.com

Leave a Reply