The Phantom Pippi Longstocking

April 30, 2017 · 3 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

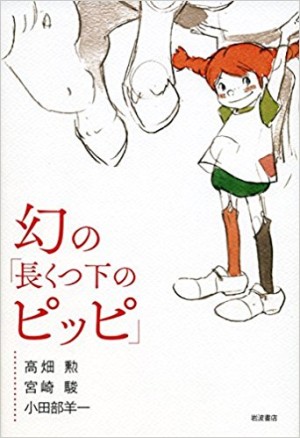

In Stockholm, Hayao Miyazaki had been awake since before dawn, watching the carpenters heading to their studios with their tin lunchboxes, and young mothers in the morning, strolling proudly with their babies. In Visby, he stared in mute amazement at the gingerbread houses and medieval stone walls, as if a fairy tale had come to life. Only allowed on the island for three hours, he pounded the pavements for a desperate 60 minutes, before collapsing in a café and staring up at the scenery. He did not notice the swarm of mosquitoes until his arms and legs were thoroughly bitten. He amassed reams of sketches, and logged every available moment in his memory. Many of these images are now preserved in the Japanese-language book The Phantom Pippi Longstocking – an account of the anime that never was, and the shadow it would cast over the later works of the animators.

In Stockholm, Hayao Miyazaki had been awake since before dawn, watching the carpenters heading to their studios with their tin lunchboxes, and young mothers in the morning, strolling proudly with their babies. In Visby, he stared in mute amazement at the gingerbread houses and medieval stone walls, as if a fairy tale had come to life. Only allowed on the island for three hours, he pounded the pavements for a desperate 60 minutes, before collapsing in a café and staring up at the scenery. He did not notice the swarm of mosquitoes until his arms and legs were thoroughly bitten. He amassed reams of sketches, and logged every available moment in his memory. Many of these images are now preserved in the Japanese-language book The Phantom Pippi Longstocking – an account of the anime that never was, and the shadow it would cast over the later works of the animators.

“I took photos, too, but it is important to just observe,” Miyazaki remembers. “Just being there was so exciting, to discover that Europe was completely different from what I’d expected. When you are pumped with adrenalin, the density of a day gets very high. All sorts of things come into perspective. Wherever you go, whatever you see, it’s all interesting.”

“I took photos, too, but it is important to just observe,” Miyazaki remembers. “Just being there was so exciting, to discover that Europe was completely different from what I’d expected. When you are pumped with adrenalin, the density of a day gets very high. All sorts of things come into perspective. Wherever you go, whatever you see, it’s all interesting.”

Miyazaki was in Sweden for the meeting that was supposed to change his life, a 1971 sit-down with Astrid Lindgren, the author of Pippi Longstocking. But despite the assurances of the studio middle-men, Lindgren had proved reluctant to set aside time to meet some anonymous Japanese cartoonists. Pleading “exhaustion”, she had avoided them for their entire trip. As the insects drained his blood in a seaside café, Miyazaki began to suspect that he had made a terrible mistake.

“I’d become a leading staff member,” says Miyazaki, “but it was clear to me that I had no future at Toei Animation. The company had decided that they would never let Isao Takahata direct another film, and to be frank, that made sense. We’d made Little Norse Prince, which had been a box office disaster.

“I was already fighting with half the workforce about their attitudes and their modes of expression. I still had a lot of friends, but even they were avoiding me in the hallways.” An animator and a shop steward, Miyazaki was feeling the pressure from both the workforce and the managers, and was looking for an escape. One inadvertently arrived when his friend and mentor Isao Takahata was offered a job at the smaller studio A-Pro.

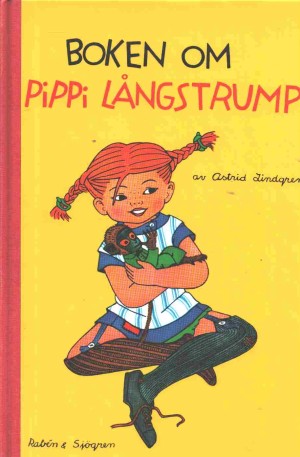

Takahata, Miyazaki and their fellow artist Yoichi Kotabe were lured away by their former colleague Yasuo Otsuka, who had left Toei two years earlier. “This was a time when the big hits were all based on sports manga like Star of the Giants,” says Miyazaki. But Otsuka had somehow managed to make a go of two seasons of The Moomins, a show based on children’s literature, and was now eyeing up the prospects of Pippi Longstocking, Astrid Lindgren’s tale of the unapologetically free, super-strong red-haired sea-captain’s daughter, who wanders the world righting wrongs with a monkey called Mr Nilsson and a horse with no name.

Takahata, Miyazaki and their fellow artist Yoichi Kotabe were lured away by their former colleague Yasuo Otsuka, who had left Toei two years earlier. “This was a time when the big hits were all based on sports manga like Star of the Giants,” says Miyazaki. But Otsuka had somehow managed to make a go of two seasons of The Moomins, a show based on children’s literature, and was now eyeing up the prospects of Pippi Longstocking, Astrid Lindgren’s tale of the unapologetically free, super-strong red-haired sea-captain’s daughter, who wanders the world righting wrongs with a monkey called Mr Nilsson and a horse with no name.

“That was remarkable for us,” says Miyazaki. “We might be able to make something meaningful, rather than just making something that was ‘only’ television. The Moomins had opened the door of hope for us. So when I heard about Pippi, I thought there would be a chance.”

Isao Takahata regards Pippi Longstocking as a watershed work in European children’s literature, fighting an establishment that had previously regarded children as bestial creatures that need to be behaviourally trained into becoming adults. Likening Astrid Lindgren to the similarly-minded writers of Japan’s ‘Child-Heart’ movement, Takahata describes Pippi as “a bomb that freed children’s minds to be just as they were.” It was, however, one child in particular whose influence would come to bear on Pippi, and that was the daughter of the CEO of Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, the sponsor of Star of the Giants, which in turn shilled for the corporation’s Oranamin C energy drink. Pippi became a viable project when the daughter and her mother both proclaimed their love of the stories, prompting Daikichiro Kusunobe at Tokyo Movie to actively seek acquiring the rights.

Takahata was particularly charmed with the style of Otsuka’s work on The Moomins, noting that the characters were so strongly delineated that the tale was free to deviate from the originals. Seemingly unaware of the author Tove Jansson’s horrified reaction to such liberties, he praised the first serial’s emphasis on characterisation, so that “any event” could be brought to the Moomin Valley, and the story would automatically generate itself through the characters’ varied reactions to it. Takahata was eager to try something similar with Pippi, integrating the original work into a chief-director system where an overseer would be able to coordinate separate workgroups.

There was no chance of this happening. Lindgren had loathed a 1949 film adaptation so much that she had insisted on writing the scripts herself for the 1969 13-part Swedish TV show, shot in the picturesque town of Visby. It was the producers of this version who had unwisely offered to broker a deal between her and the Japanese for a cartoon version, and who singularly failed to lure Lindgren out of her study. But it was too late; the Japanese delegation was already in Europe, with the clock ticking on their return flight.

“Back in 1971, going abroad wasn’t easy,” Miyazaki remembers. “There were no jumbo jets, and it took time and money flying via Anchorage. If I came back with nothing to show for it, people would say: ‘You went all the way to Sweden, and this is all you got!? You’re good for nothing!’ So I had to get some results.” Working on the assumption that Pippi was still going to happen, Miyazaki threw himself into designs, character studies and observations.

“Back in 1971, going abroad wasn’t easy,” Miyazaki remembers. “There were no jumbo jets, and it took time and money flying via Anchorage. If I came back with nothing to show for it, people would say: ‘You went all the way to Sweden, and this is all you got!? You’re good for nothing!’ So I had to get some results.” Working on the assumption that Pippi was still going to happen, Miyazaki threw himself into designs, character studies and observations.

Forcing himself away from the everyday open sandwiches at his Stockholm hotel, he ordered almost everything on the menu, just to see how it was prepared. He poked around the Skansen Open-Air Museum observing the Spartan furnishings and the way that the staff baked bread in old-fashioned ovens. “Before I went there,” he says, “I honestly thought that I could depict Europe without ever having to see it. But once I was there in person, I keenly felt the profundity of the real thing. I realised that although we lumped it all in as ‘Europe’ everything changes depending on where you are. .. It was the location hunting that made me feel that way. It’s when I found myself standing at the gateway to Europe.”

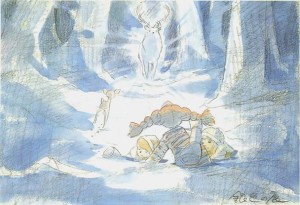

Refusing to believe that Pippi was not greenlit, Miyazaki continued his sketch output back in Japan. He would take his eldest son, Goro, to nursery each morning and then barricade himself in the studio. While his colleague Yoichi Kotabe worked on the character designs, Miyazaki recreated every moment he could remember from his Swedish trip, and took himself on flights of fancy to create images for stories as yet untold – a postal plane stuck in a tree; a mysterious glowing reindeer; a crayfish poacher on the loose. He also badgered his wife Akemi into resigning from her job to care of their younger child Keisuke: everything hinged on Pippi.

Refusing to believe that Pippi was not greenlit, Miyazaki continued his sketch output back in Japan. He would take his eldest son, Goro, to nursery each morning and then barricade himself in the studio. While his colleague Yoichi Kotabe worked on the character designs, Miyazaki recreated every moment he could remember from his Swedish trip, and took himself on flights of fancy to create images for stories as yet untold – a postal plane stuck in a tree; a mysterious glowing reindeer; a crayfish poacher on the loose. He also badgered his wife Akemi into resigning from her job to care of their younger child Keisuke: everything hinged on Pippi.

But Pippi Longstocking: The Anime never happened. There is no real evidence for Lindgren’s reluctance at the Japanese end, apart from a cryptic comment from Tokyo Movie’s Keishi Yamazaki, who thought that she had once said in a TV programme that Japanese animation was “too violent”. Where on Earth she got that idea from in 1971 is anyone’s guess — I like to imagine a Stockholm tea-time coven of famous children’s authors, complaining about foreign cartoons. But Lindgren was adamant that there would be no animation, leaving the Japanese with a stack of research materials they could never use. Or could they..?

In 1972, as relations normalised between Japan and the People’s Republic of China, Tokyo Zoo received a gift of two pandas. The subsequent outbreak of panda-mania coincided very neatly with a project Takahata had pitched to recycle some of the Pipi materials. The new story would look like an episode of “Pipi & the Pandas” in all but name, with a freckled, red-haired girl of fearsomely independent means, somehow coming to live in a surreal style with a pair of talking bears. Perhaps reflecting the childcare and work issues of that time in Miyazaki’s life, much of their dialogue revolves around when fathers are supposed to be at work. Panda Go Panda (1972) was released in the Christmas holidays as part of an anthology package in Toho Cinemas. Many such anthology shows are obscure today – indeed, Panda Go Panda might itself have been forgotten, were it not for its makers’ later fame, and the happenstance that a second instalment, Panda Go Panda: Rainy Day Circus (1973), would allow the home video release a generation later to be feature-length.

“Even though Panda Go Panda is set in Japan,” admits Miyazaki “I used quite a few things in the house and the characters that had been prepared for Pippi.” But there were other elements of the unused materials that would crop up later in Miyazaki’s work. A large swing, strung from a tree, would be repurposed as part of his landmark work on Heidi: Girl of the Alps. Most iconically, his memories of Visby would be plundered to make the town of Koriko in Kiki’s Delivery Service. The sharp-eyed Miyazaki fan is also likely to detect foreshadowings of the forest god of Princess Mononoke in the eerie reindeer spirit, but there would never be a Pippi Longstocking anime.

“I quit Toei Animation to work on it,” says Miyazaki, “so, of course, I was really keen to make it. But at the same time, I did truly understand Lindgren’s reluctance to see it turned into a cartoon. I do feel that if we had been allowed to make it, she would have changed her mind. But you never know until you do it, do you?”

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History. The Phantom Pippi Longstocking (Maboroshi no Nagagutsu-shita no Pippi) by Isao Takahata, Hayao Miyazaki and Yoichi Kotabe, is published in Japanese by Iwanami Shoten.

anime, Astrid Lindgren, books, Hayao Miyazaki, Japan, Jonathan Clements, Sweden, The Moomins

Pal

October 23, 2021 4:46 am

Hiya. There's a rumor that Lindgren was warned by Jansson about the awful job Miyazaki's affiliated studio had done with her show (in her opinion). It seems that the specific Moomin anime never aired in Sweden, and there were literally two anime airing in Sweden at the time (I'm surprised that there were any, really), one possibly being violent. I don't really think that Lindgren would have seen either of these shows, nor was she necessarily shy about licensing agreements. Jansson and Lindgren were good friends, they've even been in photographs together and are considered constituents. Do you think that this rumor holds any light, and do you know where I could learn more if this rumor rings a bell? Thanks!

Jonathan Clements

October 23, 2021 7:43 am

Keishi Yamazaki in his book Terebi Anime Damashi [Spirit of TV Anime] (Tokyo: Kōdansha Gendai Shinsha, 2005), p.161, says that he had heard that Lindgren's objection was that she thought that Japanese animation was too violent, but I don't think he specifically states that the idea was planted in her mind by Jansson. Kaori Chiba's book Heidi ga Umareta Hi [The Day Heidi was Born] (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2017), pp.45-9 includes an amusing account of a meeting between Jansson and the Moomin people, which may also throw some light on her opinions regarding anime. Pages 50-52 summarise the letter of complaint Jansson sent to the studio after she saw the finished product. Considering the lack of detail in most Japanese accounts -- Eiichi Yamamoto, for example, in his memoirs, describes Jansson as a "Norwegian cartoonist" -- my guess is that for an exact account you will need to go to Jansson or Lindgren's diaries and letters. I'm afraid I have only read Lindgren's 1940s diaries, not later ones that might shed more light on this. Letters From Tove (Sort of Books, 2019), does contain some amusing notes of Jansson's attitude towards the Moomins adaptation, and her unease with the level of merchandising and "wretched business". Tuula Karjalainen's Tove Jansson: Work and Love also includes some detail of Jansson's objection to the Moomins anime, and notably includes the comment (p.247) that when a surprise meeting was sprung on her by the producer "Yasmo Yamamoto", their only shared language was German. This is interesting because Yamazaki's comment above specifically uses the term "gewalt" when discussing Lindgren's attitude, which makes me think it might be a term that has come directly from Jansson. Boel Westin's Tove Jansson: Life, Art, Words (Sort of Books, 2014) also contains mentions of Jansson's relationship with Japan and the Japanese, both through her dealings on the Moomins, her two visits to Japan in the 1970s and 1990s, and her fictionalisation of her correspondence with Japanese fans. Beyond her description of the first Moomin series as "dreadful" however, there is no comment on her specifically taking Lindgren to one side and telling her not to deal with Japan. It is very, very clear, however, that by 1971 Jansson was utterly aghast at the way her work had been treated, and this would surely have been known to Lindgren, even if she had only read about it.

Pal

October 24, 2021 12:41 pm

EXTREMELY helpful, thank you!!