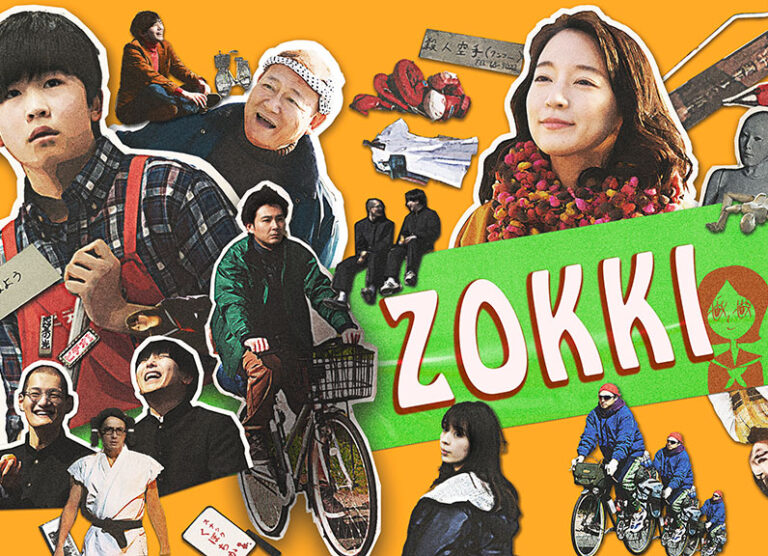

Zokki

July 5, 2022 · 0 comments

By Tom Wilmot.

Quirky Japanese comedies are a dime a dozen these days, so in order for one to truly stand out from the crowd, it needs to do something a little more unique. Such is the case for Zokki, a comedy-anthology based on Hiroyuki Ohashi’s manga collection of the same name. Helmed by a trio of actors turned directors, the film boasts an all-star cast that navigates through a series of coming-of-age tales, ranging from the horrifying to the hilarious.

Set in a small city in Aichi Prefecture, Zokki follows the everyday lives of several townsfolk who are all dealing with bizarre personal situations. While the brooding Fujimura (Ryuhei Matsuda) cycles aimlessly in search of a purpose, high schoolers Ban (Joe Kujo) and Makita (Yusaku Mori) cherish a friendship built upon the strangest of lies. These mark just two of the film’s five storylines, all of which explore the frivolous day-to-day concerns that many of us face, presented in an earnest and light-hearted manner.

In terms of its off-beat humour, dry comedic performances, and bizarre plot developments, Zokki is nothing revolutionary. However, what sets the film apart from similarly quirky Japanese comedies is the surprisingly endearing nature of its stories. No matter how odd each of the five sub-plots gets, there’s a sincerity present throughout. There’s no better example of this than the wholesome relationship that develops between classmates Makita and Ban in Takumi Saitoh’s “My Friend Ban”. While the lynchpin of their relationship is Ban’s unhealthy obsession with Makita’s elusive sister, there’s something uplifting about seeing these two oddballs save one another through an unlikely friendship. There are several more examples of understated yet touching familial ties and fleeting acquaintanceships dotted all over the film, notably between Fujimura and his rowdy fishermen friends. In amongst the laughs and absurdity, instances of human decency and community are unexpected yet welcome.

Zokki is oddly melancholic for a comedy, as things often take an introspective turn. Many of the lead characters have an inner monologue in which they mull over their purpose, past, and secrets. For example, Fujimura ponders the endless life cycle between joy and despair as he sets out on an aimless quest for self-discovery. Similarly, Ryoko Maejima’s elderly grandfather contemplates whether keeping secrets is the key to a longer life, as it gives oneself a purpose – himself having no less than 230. This type of soul-searching fits well with the various coming-of-age narratives, as high-schoolers, grown men, and fed-up video store clerks alike dwell on their life trajectory. As the various characters encounter one another in random, fleeting moments, Zokki reminds us that each person is the hero of their own unique story, much as it is in reality.

Takumi Saitoh, Naoto Takenaka, and Takayuki Yamada have all made their names as successful actors, but take up director’s chairs to adapt Ohashi’s source material, with each story being seamlessly woven together through Yutaka Kuramochi’s patchwork screenplay. Our misfits cross paths with each other courtesy of some non-linear editing that ties the loosely linked plotlines together – a Pulp Fiction of comedy, if you will. While none of the directors brings any distinct stylistic flair to their segments, their collective competence behind the camera means that Zokki is far less disjointed than one might expect. There’s a coherence and uniformity to the visuals that make the film feel like one complete project instead of the result of a directorial tug of war.

For the most part, Zokki doesn’t devolve into the fever-dream-like narrative of a Funky Forest. That being said, Naoto Takenaka’s “Father” is the stand-out short in this anthology precisely for its surrealism. While retaining the dry sense of humour that pervades the film, Takenaka’s tale leans more into horror, as the young Masaru and his troublesome father are confronted by a living mannequin during a late-night burglary. Takenaka is no stranger to horror, notably featuring in Shinya Tsukamoto’s monster flick Hiruko the Goblin, and the director’s understanding of the genre bleeds through in his vignette’s tense atmosphere. A sudden tonal shift from horror to comedy is always challenging to get right, but Takenaka handles this wonderfully as the terror of the pale, plastic figure is punctuated by Pistol Takahara’s comical screams. And who would have thought that this type of short story would also make for a heartfelt tale of father-son bonding? Needless to say, it’s these types of sequences that elevate Zokki from the average off-kilter comedy.

Hiroyuki Ohashi is something of an underground legend in the world of independent manga. Born in Aichi Prefecture in 1980, the author is a rare oddity as he endured for many years as a self-published mangaka, operating outside of the three publishing giants of Shueisha, Kodansha, and Shogakukan. Ohashi’s big break came in 2005 with On-Gaku, which was picked up for national distribution and launched the author’s late-flourishing professional career.

The three published Zokki collected editions comprise several short stories that Ohashi had been sporadically releasing during his independent days. The film draws on tales from the first two releases, Zokki A and B. The most immediately recognisable feature of Ohashi’s work is his minimal and misleadingly simple art style, which Kenji Iwaisawa faithfully imitated for his indie anime feature, On-Gaku: Our Sound.

As this live-adaptation of Zokki suggests, Ohashi’s manga works tend to focus on bizarre coming-of-age stories that are tinged with dry humour. The film’s three directors all praise the sincerity and truth behind the author’s work, with the trio having a shared love for the source material. There’s something recognisable about Ohashi’s down to earth stories, which makes even his more ludicrous tales surprisingly earnest. It’s easy to see yourself in the simplistic faces of his various misfits and oddballs, which is a quality that translates wonderfully to the manga’s live-action adaptation.

I must admit that an anime anthology of Ohashi’s manga wouldn’t be unwelcome, such is the charm of his minimalist character designs and environments. However, as far as this live-action interpretation goes, Zokki does a great job of capturing the essence of the source material. As Saitoh and Yamada allude to in an interview included with Third Window Films’ Blu-ray release, it’s hard to nail down the exact feeling that Ohashi’s stories evoke, but it’s certainly one of familiarity and comfort. Zokki is a fun, heartfelt comedy with an all-star cast that is teeming with Japanese quirkiness – what’s not to like? After the cinematic successes of On-Gaku and now Zokki, hopefully, some English translations of Ohashi’s feel-good works will emerge in due course.

Zokki is available on Amazon Prime and is released in the UK by Third Window Films.

Leave a Reply