All About Shunji Iwai

December 16, 2015 · 0 comments

By Justin Sevakis.

Back in the 1990s Japan’s local TV industry churned out a number of interesting directors who have since become big names among Japanese film aficionados. Some of them, like Hirokazu Kore-eda (After Life, Nobody Knows), have become perennial favourites of festivals and film buffs all over the world. Others, such as Yukihiko Tsutsumi, have stuck to the sort of populist entertainment that doesn’t travel well, but makes for big box office in Japan.

Back in the 1990s Japan’s local TV industry churned out a number of interesting directors who have since become big names among Japanese film aficionados. Some of them, like Hirokazu Kore-eda (After Life, Nobody Knows), have become perennial favourites of festivals and film buffs all over the world. Others, such as Yukihiko Tsutsumi, have stuck to the sort of populist entertainment that doesn’t travel well, but makes for big box office in Japan.

But of the directors of that era, Shunji Iwai is one of the most interesting, possibly because of his films, which lie somewhere in-between the accessibility of mainstream Japanese life and the surrealism that would make for an art-house release. With the notable exception of The Case of Hana and Alice, coming soon from Anime Ltd, his films aren’t easy to get, particularly in the UK, but are well worth the effort and import duties.

A Sendai native, Iwai (b. 24 January, 1963) got his start directing music videos and TV work after graduating from Yokoyama National University in 1987. For most of the early 1990s Iwai made a number of low-budget one-shot TV movies for Fuji TV. But it wasn’t until his 1993 film Fireworks, Should We See It from the Side or the Bottom?, a naturalistic depiction of children growing up in the small town of Iioka that he started attracting attention. After winning the New Directors Award from the Directors Guild of Japan, he began work on his first feature.

Love Letter (1995)

A tale of lost loves, doppelgangers and mistaken identities, Love Letter was Iwai’s first real theatrical feature. Miho Nakayama plays double duty as both protagonist Hiroko, still mourning her fiancée, who died in a mountain climbing accident two years ago, and Itsuki, a woman from her fiancée’s hometown – who mysteriously looks just like Hiroko and shares her fiancée’s name.

A tale of lost loves, doppelgangers and mistaken identities, Love Letter was Iwai’s first real theatrical feature. Miho Nakayama plays double duty as both protagonist Hiroko, still mourning her fiancée, who died in a mountain climbing accident two years ago, and Itsuki, a woman from her fiancée’s hometown – who mysteriously looks just like Hiroko and shares her fiancée’s name.

Hiroko happens upon her late fiancée’s high school yearbook one day, and with her wounds freshly opened, she decides to write a love letter to her beloved, care of his old high school. The letter gets forwarded onto the surviving (female) Itsuki. To Hiroko’s surprise, she gets a response! After some initial confusion, the two become pen pals, and both end up learning a surprising amount of new information about the man they loved.

Love Letter was a hit in Japan and a surprise hit in South Korea (which, in 1995, had only just begun officially releasing Japanese films in cinemas), and was given a theatrical run in the United States, although it never came out on DVD there. I can’t find evidence of a UK release (although the Korean DVD is easy to find and has English subtitles).

Love Letter also cemented Iwai’s partnership with Noboru Shinoda, a distinctive cinematographer who he’d worked with on one of his short TV films Undo. Shinoda lent his films a hypnotic, dream-like feel. Frequently making use of hand-held cameras, grainy film stocks, smoke machines and mist filters, Shinoda would often drift the audience through scenes, wrapping them playfully through sets and against the actors as if they were made of vapor. This drifting, ethereal feel would become a prominent motif of Iwai’s films over the next decade.

Picnic (1996)

Picnic has what is, perhaps, one of the most ingenious conceits of any low-budget film: it follows three young adult mental patients, who sneak off from the institution and happen upon a friendly priest, who gives them a Bible and wishes them well. Reading the book backwards (of course), they react to the context-less hellfire found in the book of Revelations in the only rational way one can: they become convinced the world is ending. So, the three mental patients, with the demeanor and innocence of children and limited understanding of the world, go on a journey to the “end of the earth” so that they can have a picnic and watch what will surely be the apocalypse.

Picnic has what is, perhaps, one of the most ingenious conceits of any low-budget film: it follows three young adult mental patients, who sneak off from the institution and happen upon a friendly priest, who gives them a Bible and wishes them well. Reading the book backwards (of course), they react to the context-less hellfire found in the book of Revelations in the only rational way one can: they become convinced the world is ending. So, the three mental patients, with the demeanor and innocence of children and limited understanding of the world, go on a journey to the “end of the earth” so that they can have a picnic and watch what will surely be the apocalypse.

The three young adults include the female Coco, a screechy, child-like provocateur with a penchant for black feathers; Tsumuji, an angry kid who murdered his teacher after enduring prolonged sexual abuse (as we see in some truly nightmarish dream sequences), and Satoru, who’s a dopey chronic masturbator. Together they weather the cold, abusive prison of the asylum, abandoned by their families. Through this, they maintain a certain cheeriness, and insist that they’re not REALLY going out of bounds as long as they keep walking on the wall.

Beyond the masterful performances of screechy-voiced pop singer Chara and her future husband, the famed Tadanobu Asano (Mongol, Zatoichi 2003), Picnic is given an incredible sense of space and freedom by Shinoda’s cinematography – shot in fuzzy 16mm – and by a soaring piano score by Remedios. It seems like nobody outside of Japan has seen Picnic – and even there it’s a cult film at best. That’s a real shame, because it’s an incredible film, full of bright imagination and horror at the realities of the world. I imagine that for intellectual young people with a bit of societal resentment, it will resonate quite deeply.

Picnic is an obscure film compared to the others in Iwai’s filmography, and I can find precious little background information about it. The Japanese DVD has English subtitles; the recently released Japanese Blu-ray (a longer cut with an additional scene) does not.

Swallowtail Butterfly (1996)

After Picnic, Iwai took on a hugely ambitious project: one that imagined a city way on the outskirts of urban Tokyo life, populated by destitute immigrants who’d constructed their own city after Japanese society rejected them. They called this place “YenTown”, after the money they were constantly chasing in vain. The baldly xenophobic Japanese hated them, and took to calling the immigrants themselves “Yentowns,” which the film literally admits is confusing as hell.

After Picnic, Iwai took on a hugely ambitious project: one that imagined a city way on the outskirts of urban Tokyo life, populated by destitute immigrants who’d constructed their own city after Japanese society rejected them. They called this place “YenTown”, after the money they were constantly chasing in vain. The baldly xenophobic Japanese hated them, and took to calling the immigrants themselves “Yentowns,” which the film literally admits is confusing as hell.

Yentown is a shantytown filled with brothels, drug dens and other places of ill repute, and it’s in this hellscape that a nameless teenager is left orphaned after her mother passes away. She’s sent to live with a prostitute, who dumps her on a friendly colleague named Glico (“It’s a candy – Japanese men grew up sucking on Glico,” she explains.) She takes the girl under her wing, and names her “Ageha” – butterfly.

Glico forbids Ageha to sell herself, so instead she goes to work for a collection of weirdos on the edge of town, who sabotage passing motorists and charge them a fortune to fix their cars. As she explores the Yentown underground, Ageha sees that the people of this xenophobia-induced wasteland have dreams, and have ambitions. Glico and the guys from the auto shop soon find themselves opening a night club and starting a band for their fellow Yentowns. But in Japan, nothing that an outsider builds can possibly last very long, and the dream is a fleeting one.

Despite an obviously low budget, the incredible talents at work here make the film far more than the sum of its parts. The performances are uneven – they mix Japanese, Mandarin and English – and much of it is clearly not being written or spoken by a native speaker. That said, there’s an irresistible charm to Swallowtail Butterfly, a tremendous hopefulness that cuts right through the horrifying racism laid at the feet of the Japanese people – decidedly the film’s antagonists. Adding to the somewhat punk rock attitude (if not its aesthetic) is its soundtrack by famed music producer Takeshi Kobayashi (Mr. Children, My Little Lover), who conceived of the Yen Town Band that appears in the film.

Swallowtail was ignored by the international film community, but the Japanese DVD release has English subtitles. The recently released Blu-ray does not.

April Story (1997)

Uzuki (Takako Matsu) is a shy girl from Hokkaido, who’s moving to the big city – Tokyo – for college. Her choice of school was made with the intent of following a boy she’s fallen for, but once she’s in the city she finds herself adrift. The people aren’t particularly friendly, she’s awkward and isolated. But as days go by, things begin to normalise, and Uzuki begins to find her way.

Uzuki (Takako Matsu) is a shy girl from Hokkaido, who’s moving to the big city – Tokyo – for college. Her choice of school was made with the intent of following a boy she’s fallen for, but once she’s in the city she finds herself adrift. The people aren’t particularly friendly, she’s awkward and isolated. But as days go by, things begin to normalise, and Uzuki begins to find her way.

With its short running time and barely-there storyline, there’s not much to say about April Story, other than that it’s quite pretty and charming. The film brought Iwai some further attention on the film festival scene, including winning the audience award at the 1998 Pusan International Film Festival. A Korean DVD with English subtitles is available, although no Western release exists.

All About Lily Chou-Chou (2001)

The turn of the millennia was a rough era for Japan. Its economy had been moribund for the better part of a decade, people that were promised lifetime employment were losing their jobs, and the fabric of the Japanese family was becoming badly frayed. The media took notice, in their typically exploitative, tabloid fashion, that the country’s youth were starting to go astray. Teen suicide was ludicrously high, thanks mostly to a bullying epidemic. High school girls, raised into a value system of materialism that they couldn’t afford, began engaging in enjo kosai (compensated dating), a lurid system of using automated telephone hotlines to serve as escorts. The country began to think of its young as a lost generation – one with no morals, no opportunities and no hope.

The turn of the millennia was a rough era for Japan. Its economy had been moribund for the better part of a decade, people that were promised lifetime employment were losing their jobs, and the fabric of the Japanese family was becoming badly frayed. The media took notice, in their typically exploitative, tabloid fashion, that the country’s youth were starting to go astray. Teen suicide was ludicrously high, thanks mostly to a bullying epidemic. High school girls, raised into a value system of materialism that they couldn’t afford, began engaging in enjo kosai (compensated dating), a lurid system of using automated telephone hotlines to serve as escorts. The country began to think of its young as a lost generation – one with no morals, no opportunities and no hope.

In the midst of all this, Iwai began an ambitious experiment on the internet, which was still new and exciting at the time. Along with Taiwanese art house director Edward Yang (Yi Yi – A One And A Two) and Hong Kong director Stanley Kwan (Lan Yu), Iwai conceived of a boy living in Taiwan, who was obsessed with a Cantonese pop star named Lily. Initially a music video concept, Iwai asked Takeshi Kobayashi to come up with a song for Lily, based on the image he had worked out for her. It was an image that was closer to Bjork than Taylor Swift: artful, soulful, heavy with the weight of the world. Kobayashi worked with vocalist Salyu and came up with an organic, dreamy sound heavily influenced by Lennon and McCartney.

On 1st April 2000, Iwai announced a message board called “Lily Holic”, dedicated to this non-existent pop idol. This message board was to become a novel: while Iwai would do a bulk of the writing, anybody could contribute, interact with the characters on the board, and possibly even influence the story. The project continued for six weeks, at which time the site was locked. It was published in book form in 2004, and unlocked again – seemingly for good this time – in 2011.

The story of the boy who was obsessed with the pop star and ran a message board dedicated to her became fleshed out, and in film form, gelled with Kobayashi’s dreamy music and Shimoda’s drifting, foggy, dreamy visuals to become a stirring, sad, and at times horrifying whirlpool of adolescent despair. It looks Japan’s “lost generation” deep in the eyes, and sees them for what they were: scared, depressed kids, given no meaningful guidance and acting out in the most desperate way possible. Unlike similar films produced in the West, it’s sympathetic. It almost feels like a dare: look at what you have wrought, what you have done to these kids. Look at what they have become.

The story is told through the eyes of Yuichi Hasumi (a young Hayato Ichihara, more recently known for Yakuza Apocalypse), a quiet, sensitive kid who maintains his blog, where he talks breathlessly and poetically of Lily, the “ether” she personifies, and the genius of her very being. We see him meet his best friend Hoshino (Shugo Oshinari), who used to be a great student until he started getting picked on. His family is wealthy. His mom is hot. His life just seems so much… better than Hasumi’s. The two join the school kendo club, and with some other friends, they take a trip to Okinawa.

The trip is a turning point for Hoshino. He has a near-death experience where he’s nearly gored to death by a jumping, sword-like fish. We hear later that his family’s business has gone bust, and his parents divorced. Hoshino turns from gentle into a cold and manipulative leader, quickly becoming the chief of a gang of bullies.

Hasumi is not the charismatic that his former friend is, and he finds himself relegated to the lowest level of Hoshino’s gang, kicked around by his minions. He’s assigned watch duty to a girl that Hoshino is blackmailing into enjo kosai. He watches helplessly as another girl is tormented and raped after accidentally running afoul of the girl gang of the class. The downward spiral seems unrelenting. Hasumi’s only respite is Lily, and he has tickets to go see her concert. There, he plans to meet a friend he’s only met online, and then life will be better, right?

Iwai once said of All About Lily Chou-Chou, “when you choose my [defining] posthumous work, I want it to be this.”

All About Lily Chou-Chou has been released in most territories with English subtitles, including the US and the UK.

Hana & Alice (2004)

Iwai returned to high school for his next and most commercially successful film, Hana & Alice. Far more light-hearted than Lily Chou-Chou, the film maintained the misty, surreal look that became the hallmark of Iwai’s collaborations with Shinoda. With less weighty subject matter, the cinematography takes on a spur-of-the-moment sense of whimsy, as the camera floats through scenes dreamily. It almost seems as if the film is aware of how it idealizes youth, trapping it in an old hazy photograph.

Iwai returned to high school for his next and most commercially successful film, Hana & Alice. Far more light-hearted than Lily Chou-Chou, the film maintained the misty, surreal look that became the hallmark of Iwai’s collaborations with Shinoda. With less weighty subject matter, the cinematography takes on a spur-of-the-moment sense of whimsy, as the camera floats through scenes dreamily. It almost seems as if the film is aware of how it idealizes youth, trapping it in an old hazy photograph.

The film started as a series of web shorts (sponsored by Nestlé to celebrate the 30th anniversary of their Japanese division), which Iwai began filming without having a full story in mind. Working with newcomers Anne Suzuki and Yu Aoi (the latter of whom had a minor role in Lily Chou-Chou), the three improvised a light story of two best friends with a quirky sense of humour, who often get into trouble. After six episodes, the broad strokes of a film began to take shape, and so Iwai kept shooting and expanded the story to feature-length.

Hana (Suzuki) develops a crush on a boy that the two girls quietly stalk, and as they begin attending his high school (Tezuka High School – a name not lost on its mang- loving students) Hana joins his after-school club, the Rakugo club. The boy, Masashi, is actually terrible at Rakugo (a traditional Japanese form of storytelling not too far off from what a modern stand-up comedy routine might look like in the Edo period). But Hana is smitten, and when he hits his head while walking home, she seizes her chance: she convinces the boy that he has amnesia, and that she’s his girlfriend. And that girl Alice (Aoi)? That’s his ex. Hormones and hijinks ensue.

Despite its huge success in Japan – Suzuki and Aoi became big stars after its release – Hana & Alice didn’t make much of an impact overseas. International film audiences don’t have the voracious appetite for high school stories that Japan does, and prominent scenes involving rakugo are completely lost in translation. The film was released in the US on DVD, to little fanfare.

Unfortunately, shortly after the release of Hana & Alice, cinematographer Noboru Shinoda died at age 52 of liver failure. Without his longtime collaborator, Iwai spent the next few years experimenting with writing and producing for other directors. He also made a second documentary about legendary Japanese filmmaker Kon Ichikawa (his first, made after Lily Chou-Chou, was about the 2002 Japanese National Football Team as they advanced through the World Cup).

One interesting film that came out of this era was Baton (2009), a surreal sci-fi film which was sponsored by the city of Yokohama to celebrate its 150th anniversary. The film had nothing to do with Yokohama (or even Japan) – it was set in deep space, and featured elaborate action scenes, a specialty of director Ryuhei Kitamura. Iwai provided the screenplay. The film, strangely, was shot in Japan but then rotoscoped in Adobe Flash in Los Angeles by the American studio Titmouse Inc. The film is quite flawed, particularly in its pacing (it’s three episodes, which become more talky and less exciting as time goes on), but it had an interesting visual style that was unlike nearly any animation being made in Japan at the time. And thus, Iwai had his first experience with rotoscoped animation.

Looking to reboot his film career, Iwai set out a new goal of traveling to the States and making a film in English. He got his first taste when he got the offer to direct a short film for the anthology New York, I Love You in 2008. His short, starring Orlando Bloom and Christina Ricci, was unremarkable (as was the entire film, really), but the experience made Iwai want to do a feature entirely in English.

This would prove to be a horrible, horrible mistake.

Vampire (2011)

Despite the title, the film is not at all a horror movie. Rather, it’s a study into the suicidal girls that surprisingly likable biology teacher/human blood connoisseur Simon (Kevin Zegers) lures off the internet to his house so that he can feast upon them. Inspired by an actual incident in Japan, the film features very little gore, and although there’s some violence, the girls are more coerced than assaulted. Needless to say, it’s fairly unique among films about vampires.

Despite the title, the film is not at all a horror movie. Rather, it’s a study into the suicidal girls that surprisingly likable biology teacher/human blood connoisseur Simon (Kevin Zegers) lures off the internet to his house so that he can feast upon them. Inspired by an actual incident in Japan, the film features very little gore, and although there’s some violence, the girls are more coerced than assaulted. Needless to say, it’s fairly unique among films about vampires.

Despite premiering at Sundance Film Festival, Vampire pretty much died without ever having seen sunlight. The film suffered from uneven performances and awkward dialogue (giving away the fact that Iwai didn’t know English very well), and critics panned it for its tedious pacing. Film buyers considered the film unmarketable, as its subject matter would attract nothing but horror film fans, who would likely not appreciate it. Ultimately it never found proper distribution, sitting on the market for for two years before getting a quiet direct-to-video release in the States and in Japan.

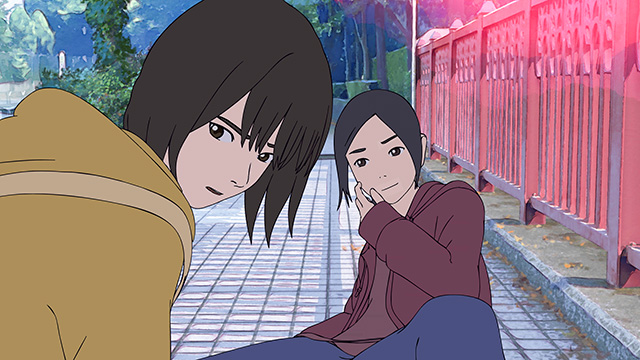

The Case of Hana & Alice (2015)

Which brings us to Iwai’s new film, The Case of Hana and Alice, which has been covered in this blog previously. Revisiting the heroines of his 2004 success, Iwai makes judicious use of rotoscoping in order to conceal the fact that his leading ladies are now pushing thirty. Thanks to the ultimate special effect of turning the film into a cod-anime, they are eternally 14 years old, and able to play their younger selves in this flashback about their first encounter. A series of misunderstandings propel them in a series of bumbling adventures in Tokyo, aided at all times by a supporting cast of indulgent strangers. Refreshingly, there’s not a shred of darkness in it.

Which brings us to Iwai’s new film, The Case of Hana and Alice, which has been covered in this blog previously. Revisiting the heroines of his 2004 success, Iwai makes judicious use of rotoscoping in order to conceal the fact that his leading ladies are now pushing thirty. Thanks to the ultimate special effect of turning the film into a cod-anime, they are eternally 14 years old, and able to play their younger selves in this flashback about their first encounter. A series of misunderstandings propel them in a series of bumbling adventures in Tokyo, aided at all times by a supporting cast of indulgent strangers. Refreshingly, there’s not a shred of darkness in it.

The use of rotoscoping also allows for some interesting compositions and scenes, playing to entirely different strengths. Anime normally contains astute observations of body language, as the animators or storyboarders chose precisely what to show. You’ll get close-up shots of a hand twitching, or micro-expressions built up by the creative staff, and such moments take the place of “acting” in animation – essentially, the animators act for the character. But with The Case of Hana & Alice there are actual actors doing that work, so it’s not case of one thing happening at a time, but a slew of little things all happening simultaneously – a huge amount of “data” compared with the amount that comes across in everyday animation. It helps fill out the film a little bit more, particularly when the story is less important than the many character moments it feeds.

In my opinion, The Case of Hana & Alice is a better film than its predecessor, which didn’t benefit so much from the Iwai-Shinoda look as their earlier films. Now, with the demands of rotoscoped animation preventing Iwai from either moving the camera or liberally applying mist to the image, Iwai is free to work out a new aesthetic. That he can do so in a familiar language, with familiar actors playing familiar characters, in a familiar land finally gives Iwai the confidence he needed. Despite a rocky production, the film is remarkably assured in its vision and its thesis about life and youth in modern Japan. It’s also very pretty.

Will this turn into a second act for Mr. Iwai? Will The Case of Hana and Alice produce a repeatable aesthetic for future projects, or is the man still finding his bearings? It’s too early to tell.

Justin Sevakis is the founder and current Answerman at Anime News Network, and owner of authoring company MediaOCD. The Case of Hana and Alice will be released by Anime Ltd in 2016.

Leave a Reply