Books: Shojo Across Media

April 13, 2019 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

Jaqueline Berndt, Kazumi Nagaike and Fusami Ogi’s new edited collection, Shojo Across Media: Exploring ‘Girl’ Practices in Contemporary Japan is another welcome addition to the expanding shelf of books specifically about Japanese popular culture aimed at female consumers.

Jaqueline Berndt, Kazumi Nagaike and Fusami Ogi’s new edited collection, Shojo Across Media: Exploring ‘Girl’ Practices in Contemporary Japan is another welcome addition to the expanding shelf of books specifically about Japanese popular culture aimed at female consumers.

Among the high points, Akiko Sugawa-Shimada looks at girls in anime, specifically magical girls, as empowering sights for female viewers; Masafumi Monden chronicles the uses and abuses of frilly fashions and princess poses; Sonoko Azuma revisits the ever-spangly world of the Takarazuka Revue and its all-girl musical extravaganzas, and Patrick Galbraith brings up the rear with a valuable account of male fans of what are supposedly “comics for girls.” But I’d like to focus on just four chapters out of fifteen to give a sense of some of the great work to be found here.

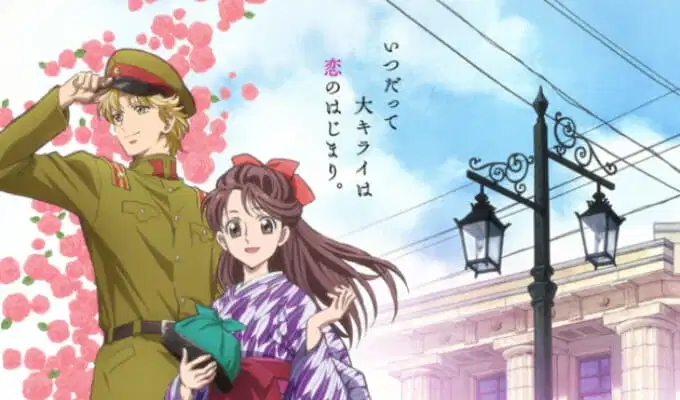

Alisa Freedman examines the rise of the schoolgirl in the early 20th century, chiefly through the portrayal of the lead character in Waki Yamato’s Here Comes Miss Modern. Some regulars at Scotland Loves Anime may remember the recent anime remake, which was a surprise hit at last year’s festival, but the original was a relatively short-lived comic series that ran for just two years in Shojo Friend, before enjoying a substantially longer afterlife as an anime show. She alludes to some delightful indicators of the disruption and kerfuffle caused by the influx of female students into public life, not the least the telling 1912 introduction of the “Flower Train”, Japan’s first-ever women-only carriage, expressly designed to give girls a safe space on their daily commute.

Freedman reveals the practicalities behind the famous “sailor suits” – a two-piece skirt and blouse was better-suited than traditional Japanese dress to sitting on one of those new-fangled chair things, and charmingly recounts fluctuations not so much in school uniform over the decade, but in the ways that girls have variously hacked and pimped their outfits. Her article is thick with fascinating detail, even in the footnotes, which point to the effects of the 1985 Equal Opportunity Law, answering a question I have long had about why women in the 1970s anime companies were sent home early, while the men stayed on to do overtime. I thought it was chivalrous, or at the very least sexist, but it turns out it was the law!

Giancarla Unser-Schutz delves into the use of language in ten popular manga, in order to work out who might be reading them – as she notes, the boy/girl division between shonen and shojo manga readerships has been heavily disrupted, not the least by publications with themselves, some of which now cheekily bill themselves as shojo for boys or shonen for girls. She gets very technical with her discussion of vocabularies and even the design of speech balloons, and points out that the gender of the author of Death Note, Tsugumi Ohba, remains a secret – “he” in most foreign coverage, “she” in some Japanese sources, and “they” on Wikipedia, at least this morning. This is great stuff – I’ve seen some statistical analyses of manga before, but too many of them use a sample that’s way too small, or fail to grasp the nuances between different publications. Unser-Schutz produces some compelling data, and leaves her working out in the open for others to test.

Giancarla Unser-Schutz delves into the use of language in ten popular manga, in order to work out who might be reading them – as she notes, the boy/girl division between shonen and shojo manga readerships has been heavily disrupted, not the least by publications with themselves, some of which now cheekily bill themselves as shojo for boys or shonen for girls. She gets very technical with her discussion of vocabularies and even the design of speech balloons, and points out that the gender of the author of Death Note, Tsugumi Ohba, remains a secret – “he” in most foreign coverage, “she” in some Japanese sources, and “they” on Wikipedia, at least this morning. This is great stuff – I’ve seen some statistical analyses of manga before, but too many of them use a sample that’s way too small, or fail to grasp the nuances between different publications. Unser-Schutz produces some compelling data, and leaves her working out in the open for others to test.

Two articles are ground-breaking investigations of media that, while not necessarily all that new, are still woefully overlooked. In the first, Kazumi Nagaike and Raymond Langley write about the “cell-phone novel”, which is, to be frank, a far more telling and descriptive term for a subset of what many readers would otherwise bundle under the catch-all name of “light novels.” The authors handily collate pre-existing research about the story-telling and narrative style of a cell-phone novel, pointing to the manner in which such stories replicate and imitate email. They, and the critics they cite, make the best case I have yet seen for such works as a new literary mode, and go on to discuss the more rarefied form of the “dream novel”, an under-reported fad in which the reader’s own name is interpolated into a text by an online engine, turning her into one of the main characters.

Two articles are ground-breaking investigations of media that, while not necessarily all that new, are still woefully overlooked. In the first, Kazumi Nagaike and Raymond Langley write about the “cell-phone novel”, which is, to be frank, a far more telling and descriptive term for a subset of what many readers would otherwise bundle under the catch-all name of “light novels.” The authors handily collate pre-existing research about the story-telling and narrative style of a cell-phone novel, pointing to the manner in which such stories replicate and imitate email. They, and the critics they cite, make the best case I have yet seen for such works as a new literary mode, and go on to discuss the more rarefied form of the “dream novel”, an under-reported fad in which the reader’s own name is interpolated into a text by an online engine, turning her into one of the main characters.

The second is just as strikingly original, as Minori Ishida examines the world of audio drama for women, specifically boys’-love CDs and “audio porn”. Audio dramas are another under-studied area in Japanese popular culture, because they usually lack visual aids to comprehension. This affects not only the willingness of researchers to cover them, but of audiences to sit still and hear about them, and of journalists to write about them – I gave up more than 20 years ago in Anime UK magazine, because we never had enough pictures to hang the text on, and most of our readers would never understand them anyway. Ishida offers an unprecedented glimpse… er… soundbite of CDs that offer erotic diversions for female listeners, including the “Situation” CDs, which exploit stereophonic sound to put the listener quite literally in the middle of the action. She alludes to way in which CDs can offer a safe space of their own, on sale in anime shops rather than sex shops, and thereby more accessible to their fans. It’s an intriguing facet of an interesting topic, and well worth reading for anyone with an academic interest in Japanese popular culture for women.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History. Shojo Across Media: Exploring ‘Girl’ Practices in Contemporary Japan is published by Palgrave Macmillan.

Leave a Reply