Hiroshi Hirata (1937-2021)

December 17, 2021 · 1 comment

The manga artist Hiroshi Hirata, who died last week, spent his formative years struggling to make ends meet in a poverty-stricken Japan. He was born in Tokyo, where his parents were preachers for the Tenrikyo Buddhist sect, but was evacuated to the order’s heartland, Tenri, in Nara to avoid Allied air raids. He drew his first comics, four-panel cartoons for the Tenri Junior High school newsletter, but was frequently absent in the afternoons to help at his father’s water pump workshop. As a result, his childhood nickname was Sabori no Hirata (Hirata the Truant). His early aptitude was not for art but for mechanics – he later said that his favourite magazine was an electrical engineer, and that as a young teenager, he built his own film projector from discarded and broken machines. Moving on to Tenri High, he spent a single day as a freshman before dropping out to work full-time for his father.

After his father’s sudden death in 1954, the teenage Hirata went to work to support his family. There were attempts by his relatives to persuade him to take an induction course to work for the Tenrikyo organisation, but after a deeply unpleasant spell in hospital, where a malignant caecum led to an intestinal operation conducted without anaesthetic, he went to work for the Osaka construction company Kintetsu. He did eventually take the preacher course, but did not pursue it further.

A chance encounter with an old classmate from school led him to draw a manga overnight, selling Deadly Sword of Love and Hate to the magazine Mazo (“Demon”), published by Hinomaru. Having read very little manga himself, Hirata relied largely on the resources of the Tenri library and second-hand book marts, swiftly developing a love of historical adventures. Within a couple of years, he was one of the magazine’s star artists, leading him to change the spelling of his name so that it now included a shi that meant “HISTORY.” He specialised in the Tokugawa-era, the 17th, 18th and 19th century in Japan, developing an obsession with the minutiae for its history and attitudes that would obsess him for the rest of his life, even to the extent of depicting himself as a swordsman in a self-portrait on his website.

Not every manga was success. In 1962, his story Bloody Stumps Samurai was conceived as a proletarian protest in the style of his colleague Sanpei Shirato – a revenge thriller in which a martial artist turns on the teacher who bullies him, and hunts down the rest of the students who mocked him for being a burakumin – a member of Japan’s “untouchable” caste, supposedly disbanded, but in fact still subject to discrimination and exclusion. Hirata’s intention had been to make a hero out of a member of the underclass, but the story led to strident protests from the Buraku Liberation League, who saw it merely as a perpetuation of stereotypes that portrayed the burakumin as violent and cruel.

Hirata was summoned along with his publisher to a meeting at the home of the Osaka BLL chapter head – Hirata was so poor at the time that he couldn’t afford his own train fare. He described the meeting as a confrontation with the well-spoken and gentlemanly leader, Kiichi Matsuda, and a bunch of imposing men who reminded Hirata of gangsters. That, of course, was precisely the sort of language and associations that the BLL was hyper-sensitive about in the first place. Copies of Bloody Stumps Samurai were publicly burned, the title was officially rendered out of print, and the publishers timidly agreed to let the editor of a buraku newspaper reframe the story in a politically correct manner. When this turned out to be an unpublishable rewrite by a man who, in Hirata’s opinion, didn’t even like comics, the editor was paid a kill-fee and the matter was dropped.

Bloody Stumps Samurai became something of a cause celebré among manga artists, with contraband copies cherished in many collections – it was not officially reprinted until the 1990s, in an edition that redacted some of the original language, replacing entire speech bubbles with anonymous crosses. In the interim, Hirata published a toned-down rewrite of his own, Tell Us (1968). In 2005, the original became the first manga to be published in Hindi, as part of an ill-advised attempt by a Japanese entrepreneur to “introduce” the locals to comics, which he presumed they didn’t already know about. Ryan Holmberg, who would eventually translate it into English in 2019, called it “too radical for its own good.”

In 1966, Hirata gave up on the small-time manga industry and migrated to Tokyo, where he found work with the large-scale publishers of Weekly Shonen King and Comic Magazine. He also worked on manga versions tied to several other media, drawing adaptations of Zatoichi, and Hideo Gosha’s samurai films Hitokiri (1969) and Goyokin (1969). Newly married, and soon with two children to support, he enjoyed critical acclaim as part of the era’s “gekiga” boom, but still struggled to make ends meet. Whereas colleagues such as Takao Saito were happy to industrialise the manga creation process by taking on multiple assistants, Hirata insisted on often working solo. It made him a manga auteur… but one without any money.

He found an unlikely celebrity supporter in the form of the author Yukio Mishima. “The pay-library comics that once could only be purchased in the flea markets of Ueno had ten times more vulgarity, cruelty, wild abandon and vitality than today,” Mishima wrote. “But in Hiroshi Hirata’s samurai comics, with their direct, serious art style, I find a nostalgia for the kamishibai of old, and a sensibility in the manner of the violent warrior prints of the late Edo period.”

Several of Hirata’s works were truncated by his own poverty or his refusal to compromise. The Just Heroes of Satsuma required spread after spread of huge, intricate depictions of samurai life, and from which Hirata simply walked away after five years. It was published in English, some years later, under its original Japanese title of Satsuma Gishiden, and praised by Jason Thompson for its meticulous attention to period detail. “[T]here’s a 10-page sequence just showing [people] working at their professions: treecutter, carpenter, farmer, geta maker, paper maker, etc.,” wrote Thompson in a review for the Anime News Network. “It serves no story purpose, but it feels like Hirata is waving his fist at the audience and shouting ‘JUST TRY TO FIND SOMEONE WHO KNOWS MORE ABOUT THE TOKUGAWA ERA THAN ME! I DARE YOU!’”

Ryan Holmberg agreed, implying that Hirata’s 1980s work would have been precisely the sort of thing that Mishima complained about. “Hirata’s draughtsmanship is obviously superhuman,” he wrote, “but that alone does not a compelling comic make…. Hirata of the 1960s is so much more interesting.”

In 1982, Hirata was one of the earliest Japanese artists to see print in the English language, with the story “Two Samurai” in Manga magazine – an odd historical curio that has baffled the manga experts, but is believed to have been a prototype put together by a Japanese publisher in the hope of cracking the American market.

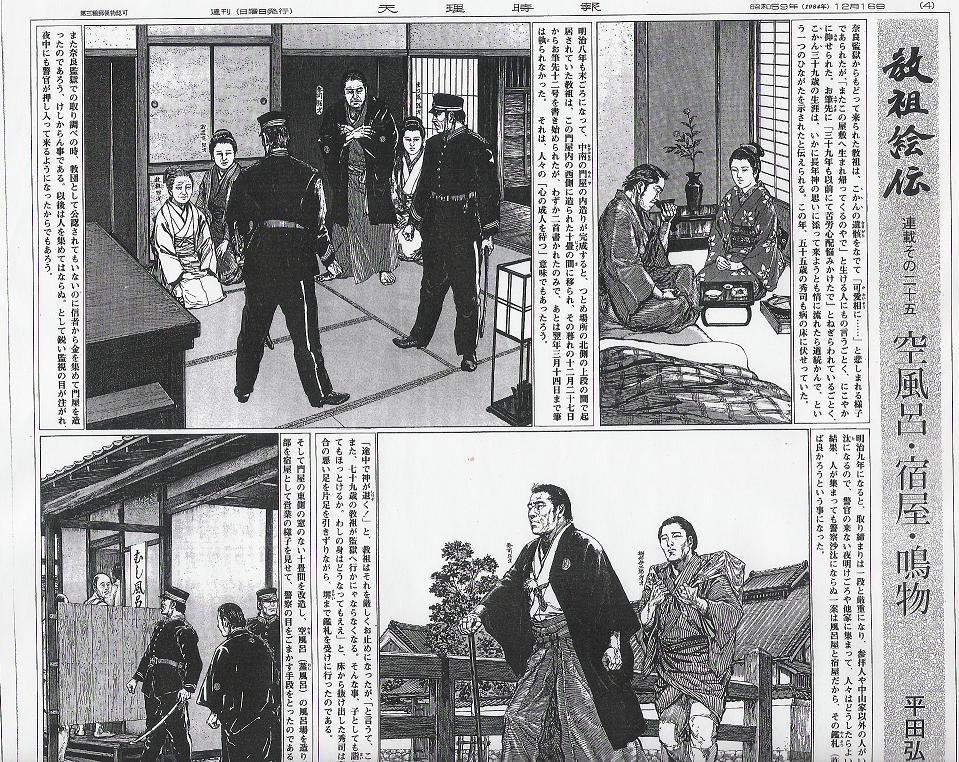

In the same year, exhausted by the effort involved for relatively little return, Hirata gave up on manga entirely and briefly went back to work in the electrical industry. Asked by the Tenrikyo to provide an illustrated biography about the sect’s charismatic 19th-century leader, his manga work Portrait of the Founder (1983) focussed increasingly on the gaps between the actions of the institution versus the actual words of the guru Miki Nakayama. It led to a falling out between Hirata and the religion, and the story was left incomplete.

By the 1980s, Hirata faced a series of personal crises of faith and bereavement. He actively questioned his own yearning to draw, and spent increasing amounts of time tinkering with synthesisers and computers. Ironically, this led to a new flourishing of his artwork, as he became an enthusiastic advocate of the Macintosh computer, writing a column on digital artwork for MACLIFE magazine, and becoming a fixture at Mac Expos. Around the turn of the century, he was elated to discover the potential of the Macintosh for digitising and preserving his intricate artwork, leading to a flurry of reprints and e-editions.

He did not, however, welcome the use of computers to draw upon, always preferring to work with ink and paper. It was in this medium that he found much of his widest footprint, not merely as an artist, but as a calligrapher. Whenever someone needed a dash of thick, bold Japanese writing, it seemed that Hirata was the first choice, leading to some of his most widely recognisable work to appear on the covers of works by others. It was his brushstrokes that slashed out the title of the game Ys on the X68000, his “BANDIT” that scrawled across the covers of Masamichi Kawabe’s Bandit: The False Taiheiki, his splotchy “SHIGURUI” that formed the logo for Takayuki Yamaguchi’s Shigurui: Death Frenzy, his Zorro-like brushwork on the covers of Nisio Isin’s Katanagatari (above). If you wanted a samurai look, you commissioned your logo from Hiroshi Hirata, whose version of the hero’s name adorned the poster for Mamoru Oshii’s Musashi: Dream of the Last Samurai – the English-language release struggled to imitate it, but failed.

Tardily recognised as an iconic and accomplished artistic treasure, Hirata received a lifetime achievement award from the Japan Cartoonists Association in 2013. The nature of his artwork made it an ideal choice for mounting in exhibitions, and a retrospective of his work, originally shown at the Kyoto International Museum, subsequently toured abroad. His character Hanshiro Kubidai, the “Chief Underwriter” from his manga The Wages of Dishonour, became oddly popular in Europe, leading Hirata to be invited to draw large-scale versions of at events in Spain, Monaco and France.

Arguably the most famous, and most widely seen piece of his work was just three Japanese characters, the symbols for A, KI and RA, in a bold, red brush, daubed with his characteristic surety. They formed part of the logo for the manga and anime releases of Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira, and were hence seen all around the world.

Giulyano

August 20, 2024 12:18 pm

Esperava algo sobre quando ele começou a desenhar no computador, que sim, ele desenhou no digital por mais que achava melhor para digitalizar, eu só não sei quando ele começou no digital.