Sanpei Shirato (1932-2021)

October 26, 2021 · 0 comments

When asked by an interviewer why he became a manga creator, the late Sanpei Shirato answered bluntly: “I needed to eat.” This seemingly simple reply encapsulated much of his own gritty, materialist attitude towards storytelling. He was always aware of the big picture, of the great weight of history as it marched along, but focussed incessantly on the way such matters impacted the everyday.

He was born as Noboru Okamoto in February 1932, in the part of Tokyo that would soon be renamed Suginami. His father, Toki Okamoto was a left-wing artist persecuted by the authorities – some of the family’s house-moves were aimed at finding him treatment for ongoing medical conditions resulting from police-administered beatings. His maternal uncle, Taro Shioya, was a translator of English science fiction and German children’s books, whose Best Short Stories of India was a wartime hit, and the source of several story ideas for his nephew. His brother Tetsuji Okamoto, who would die only four days after him, was his long-time collaborator and assistant.

Young enough to have avoided the draft, he struggled to make ends meet in post-war Japan. Dropping out of school in his teens, he first found work in a denture factory in Nakano, and helped out in his father’s back-room art studio, colouring the image boards used by wandering kamishibai storytellers. It was in this format that he made his first story sale, aged 19, the comedy Mister Mochan, which he would draw for the next three years.

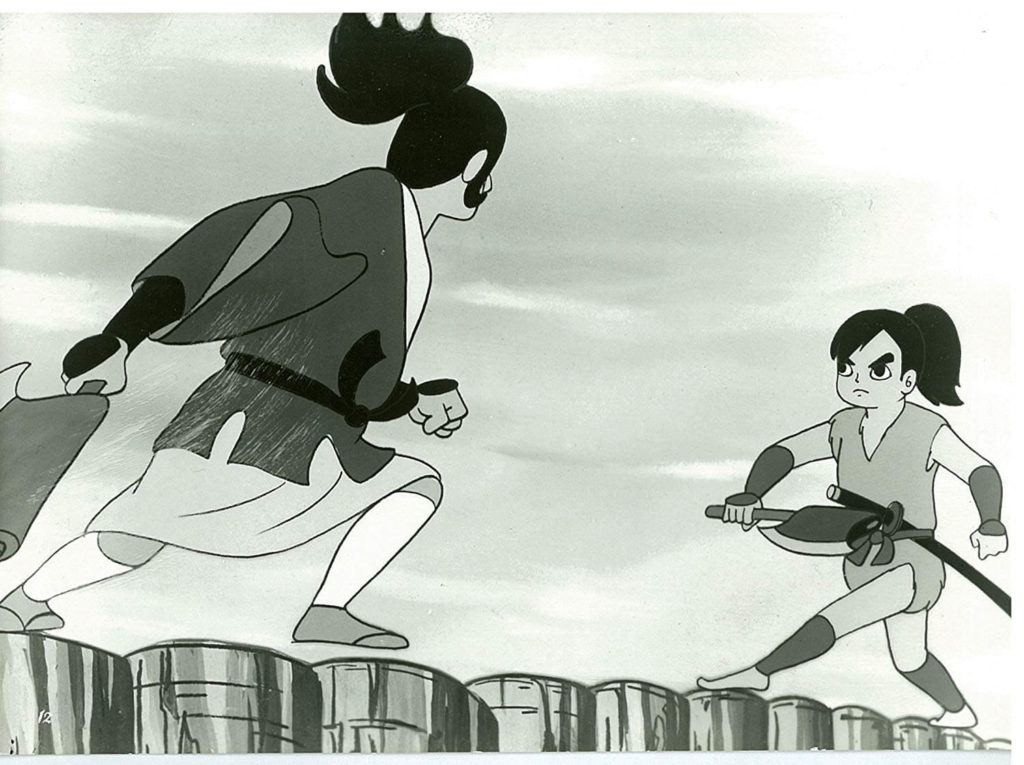

Kamishibai (pictured) flourished in the post-war ruins, where it offered cheap entertainment for children, and gainful employment for many a demobbed soldier. Its popularity began to fade with the advent of television, leading him to begin drawing comics, beginning with Mamoru-chan (1956) for the magazine Children’s Guardian. The most lucrative form of comics work, however, was in creating full-length stories for the rental book market – magazines paid twice as well, but only after publication, whereas the rental publishers paid on delivery. He began under a pen-name derived from Shirato, the name of a soldier alumnus of his high school, and Sanpei (“Number Three”), his nickname among his housemates. During the same period, he flirted with the idea of joining the Japanese Communist Party, and volunteered to deliver copies of its newspaper, Akahata (“Red Flag”).

Alongside the novelist Futaro Yamada, Shirato became a key figure in a new subgenre of Japanese fiction, deriving its inspiration from the restrictions of post-war publishing. During the US Occupation, all discussion of the samurai had been forbidden, nudging left-wing artists into producing new stories about a previously unsung and largely unmentioned underclass. Such tales were an irresistible temptation for Shirato, who was intimately involved with the struggles of Japan’s subaltern people – people of Korean descent and the “untouchable” caste of the burakumin. He leapt at the chance to narrate an account of Japanese history that focussed not on the lords and generals of samurai nobility, but on the starveling farmers and vagrants caught up in their wars – the flotsam of the samurai era, now reimagined not merely as victims, but as a pariah elite of skilled assassins – the ninja.

After faltering first steps with Kogarashi Warrior (1957), a story defeated by the collapse of its publisher, he found true success with Chronicle of a Ninja’s Martial Achievements (1959), a stylish manga that incorporated an omniscient narrator commenting on proceedings, as if the kamishibai storytellers of old had been reborn within the pages of a comic. Shirato’s desire to embrace adult storylines would cause numerous conflicts for him, not the least with his unflinching portrayal of the messy business of heroism. “I had a beggar girl set fire to herself,” he remembered, “becoming a signal beacon in order to warn the warrior who had previously saved her life. Should I only draw the beauty of her spirit? Or the ugliness of a burnt corpse? I chose not to turn away from the dead body.” This, he would later say, is what “historical materialism” actually meant – not just the great, noble ideas, but the way they were implemented at the sharp end of politics. His controversies included a run-in with the Japanese Parents and Teachers Association after two characters were seen kissing each other in a “children’s” comic, as well as his landmark The Girl Who Disappeared (1959), which chronicled the experience of a Hiroshima orphan, growing up in a post-war period amid the persecution of Korean immigrants and denial of the after-effects of atomic weapons.

By 1963, Shirato was being lauded as a “children’s” comic creator, for his ninja story Sasuke, which had as its background the 1669 Shakushain revolt by Japan’s aboriginal Ainu people, and his adaptations of the animal tales of Ernest Seton. He was, however, on the verge of breaking new ground in manga, becoming one of the key figures in a new, avant-garde manga magazine that pushed comics as an adult medium. Although the precise chain of events is unclear, he might have even provided its title, Garo, which may have derived from a character in one of his manga.

Inevitably, his works were adapted for television and film. His first big success in the TV world was Fujimaru the Wind Ninja (a.k.a. Ninja the Wonderboy), broadcast in 1964. The original manga had a different title, but in a tense compromise for Shirato the committed socialist, the show was renamed to establish a link with its sponsor, Fujisawa Pharmaceuticals. Each episode of the rollicking boys’ drama would open with a Fujimaru theme song that transformed into a jingle for Fujisawa. Notably, it would close with a live-action sequence in which a breathless interviewer would quiz Masaaki Hatsumi, an accomplished martial artist who claimed to know the secrets of the ninja world, and who imparted them to an entire generation of Japanese boys – Hatsumi would go on to write a book about “ninjutsu” and completely confuse historians of the martial arts thereafter.

The Legend of Kamui (Kamui-den) ran in Garo from 1964 to 1971. Simultaneously, Kamui: The Untold Story (Kamui Gaiden) ran in Shonen Sunday, a magazine for teenage boys. The latter was then resurrected in Big Comic, a magazine for adult males in 1982 to 1987, running across 116 chapters and spanning 18 story arcs. It was then rebooted in the same magazine from 1988-2000, revealing that the original Kamui had a twin brother, also called Kamui, whose adventures formed an entire set of Kamui apocrypha. Although Shirato made several attempts to write on other subjects, most notably a six-year stint in the 1970s writing an anthology of world myths for Big Comic, Kamui swamped all his other output.

The combined sales for both Kamui serials top ten million copies in Japan. Kamui has hence passed through a number of transformations, from adult comic, to teen comic, and back to adult again. The Big Comic adventures included “Wind on the Black Hill”, “House of Thieves” and “Blood Sucker”, but perhaps the best known was the 15-chapter arc known as “The Isle of Sugaru.” It was this story, running from April to October 1982, which was eventually snapped up by the American publisher Viz Communications and translated into English as Legend of Kamui. It was one of the first manga to be translated into English. Subsequently, editions appeared in many other languages – mention Kamui Gaiden to a non-Japanese manga fan, and the 1980s retelling of “Isle of Sugaru” is likely to be the only one of dozens of Kamui stories that they have actually read, particularly since it formed the nucleus of the more recent Kamui live-action film.

Shirato continued to emphasise the struggle of the working class. The action in the Kamui manga would cease for page after page of pastoral scenes – fisherman at work, women gutting fish, hunters in the forest – all glorifying the mundane achievements of daily life. As in Yoichi Sai’s movie adaptation, the ninja action is often marginalised for a loving focus on the joys of a job well done, such as the manufacture of a fishing lure.

Tales of the ninja dominated Shirato’s output for the last forty years of his career. Thanks to Kamui’s appearance in multiple venues and forms, Shirato’s anti-hero became an icon of an entire sub-genre in Japanese fiction. Although Shirato wrote other ninja stories, including Watari (1965) and Red Eye (1961), both of which chronicled internecine strife among the ninja clans, and Sasuke (1961) cited by the artist Masashi Kishimoto as a major influence on the world-beating Naruto, it was Kamui for which he will largely be remembered. But Kamui was not the same story throughout its lifespan – like its author, it changed with the times. Its early days in the 1960s saw its underclass heroes fighting corruption in high places, making its hero a poster-boy for Japan’s modern Left. But Kamui, too, is betrayed by his own people, and flees the manipulations of factional in-fighting among the ninja themselves. Throughout the real-world Cold War and its aftermath, Kamui formed a commentary on the fate and moral tangles of the socialist ideals that had formed such a crucial part of Shirato’s upbringing and formative years.

Not everybody appreciated Shirato’s allegories – his most famous critic was Hayao Miyazaki (once an animator on the Fujimaru series), who commented that Kamui was rooted in Shirato’s own emotional reaction to 1960s politics, and that its depiction of history was not only misleading, but blatantly unworkable. In particular, Miyazaki took issue with the original ending of Chronicle of a Ninja’s Martial Achievements, which ended with the warlord Oda Nobunaga confiscating the weapons that might allow the oppressed peasantry to rise up against the samurai (which did happen), but also literally laying waste to Japan, leaving the people to struggle through a man-made famine.

But Shirato’s interest in history was in the pivotal moments where, despite the overwhelming sense it could not be stopped or turned aside from its course, mere humans were still able to affect it. “I think,” he once said, “that the so-called ‘hero’ is merely someone who is able to grasp and affect a certain moment, according to the laws of history. During Japan’s civil war period, there were all sorts of people, driving forces that turned over the pages of history… You might think it is inevitable, but human beings can become the agents of real change through how they expend their lives. That’s what I think.”

Leave a Reply