Books: A Tokyo Romance

July 4, 2019 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

Poor boy that I am, when I arrived in Japan I did so knowing nobody and nothing – author Ian Buruma turns out to have the Hollywood director John Schlesinger for an uncle, and an oil-business bigwig with a Tokyo mansion for a “distant relative” in 1975. He also already has a Japanese girlfriend ready to up stakes and return to her homeland with him – poor Sumie Tani is relegated to the margins of a book called A Tokyo Romance – barely mentioned in the first 40 pages, as Buruma bums around town meeting people who boast they knew Yukio Mishima.

Poor boy that I am, when I arrived in Japan I did so knowing nobody and nothing – author Ian Buruma turns out to have the Hollywood director John Schlesinger for an uncle, and an oil-business bigwig with a Tokyo mansion for a “distant relative” in 1975. He also already has a Japanese girlfriend ready to up stakes and return to her homeland with him – poor Sumie Tani is relegated to the margins of a book called A Tokyo Romance – barely mentioned in the first 40 pages, as Buruma bums around town meeting people who boast they knew Yukio Mishima.

Eventually, he gets around to talking about the woman who must have played a major role in luring him to Japan in the first place, grudgingly ticking off her family history, and observing, with a trenchant eye, that the supposed harmony of multi-generational Japanese family life was utter bilge, and that having seen Sumie’s parents and siblings bickering with her grandfather, he could totally understand why so many modern Japanese ran gratefully for the isolation of suburban tower blocks. But there is little more of her in this book, and a couple of chapters later, she is discarded as easily as Pinkerton casts aside his Butterfly. At the very end, she wanders back in, still without anything to say, to marry him, although he mentions within a sentence or two that they would also get divorced.

A Tokyo Romance is not about that sort of romance. It’s about the young Buruma’s deluded, whimsical obsession with a distant land to which he, like many expats, flees because of the privilege it offers him for being different – a rebellion, he confesses, not against Japan, but against the home he left behind. It all starts for him with a screening of Francois Truffaut’s Bed & Board (pictured), in which he falls in love with the character of Kyoko, “willowy, with long shiny black hair and dark eyes set in a pale moon face… I wanted a Kyoko in my life, perhaps even more than one. How happy I would be in a land of Kyokos.”

Buruma is aware, at least with the hindsight of old age, that the Japan of his youth was idealised and orientalist, little different from the yearnings of Pierre Loti, who wrote in the 19th century of his desire to rent the attentions of “a little yellow-skinned woman with black hair” and live with her “in a little paper house.” But as the film critic Donald Richie points out to him, he will never be accepted by the Japanese, and he might as well embrace his status as an outsider, in a world where, in Buruma’s own words the constrictions of Japanese society turn the locals into “human beings trimmed like bonsai trees.”

Those must have been the days, as Buruma describes “Japanese girls whose taste for gaijin matched our own interest in Japanese girls,” including the usual rack of nutters, such as the woman who keeps on imagining that her lover is Eric Clapton, even to the extent of calling out “Eric!” in the throes of passion. “Ethnic or cultural fetishism,” writes Buruma, “did not just go one way.” He cites enfant terrible Amy Yamada as a case in point, fetishising her black boyfriends just as much as any fanboy bragging about his hot Japanese babe.

Those must have been the days, as Buruma describes “Japanese girls whose taste for gaijin matched our own interest in Japanese girls,” including the usual rack of nutters, such as the woman who keeps on imagining that her lover is Eric Clapton, even to the extent of calling out “Eric!” in the throes of passion. “Ethnic or cultural fetishism,” writes Buruma, “did not just go one way.” He cites enfant terrible Amy Yamada as a case in point, fetishising her black boyfriends just as much as any fanboy bragging about his hot Japanese babe.

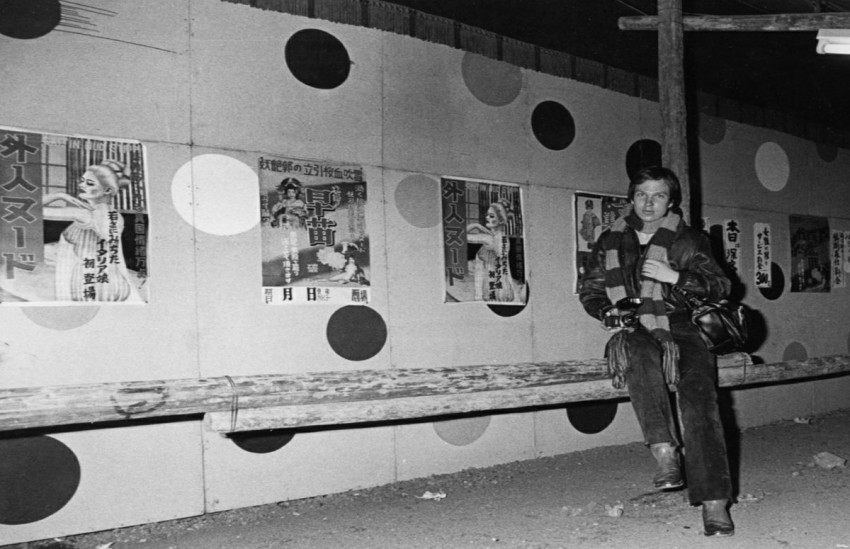

Buruma’s Tokyo tales are a wonderful collage of ghastly poseurs and jocular racists, avant-garde theatrical performances, peep shows and strip clubs, forgotten circus celebrities and lost districts, which he wanders with the same melancholy interest as his literary hero Kafu Nagai. It is a lurid, lost Tokyo before the transforming influences of social media or wi-fi, where one must find books by reaching out and picking them up, and make appointments by speaking to human beings. It is also a world almost as insular as the Shogun’s Japan. Few Japanese, Buruma notes, had the means to leave the country, turning its capital into a side-show of theme-park mockeries of the Other and Far Away. “There was something theatrical, even hallucinatory about the cityscape itself, where nothing was understated; representations of products, places, entertainments, restaurants, fashion and so on were everywhere screaming for attention.”

I particularly enjoyed Buruma’s passive-aggressive celebration of his sometime travel buddy Donald Richie, an old Japan hand highly thought of in the world of Japanese film studies, but clearly something of an arse. His comments here flit, as they did in real life, between moments of undeniable wisdom and catty put-downs, and Buruma takes delicious pleasure in observing that Richie the great Japan expert couldn’t actually read Japanese.

You can’t defame the dead, although some of Buruma’s other observations could have done with a little fact-checking. It’s difficult to imagine, for example, that the denizens of a Tokyo coffee house in 1975 enjoyed listening to Richard Clayderman, whose first record was not recorded until a year later. But as Buruma notes himself, he kept no diary some four decades ago, and much of his reminiscences here have been inspired solely by photographs from the 1970s, impressions not necessarily in chronological order, but of a whole era. He is looking through his photo album, and doing his best to fill in the blanks about plays he saw and films he… was in the same building as.

Was anyone even watching the films? Buruma reports a visit with Richie to one Tokyo cinema screening a forgotten porn movie, in which the entire audience comprised men having it off with one another. The film on offer was merely a smokescreen to cover what amounted to a cheap knocking shop. That would explain an awful lot about Japanese film, both then and now.

Long-term attendees of Scotland Loves Anime may remember 2011 and director Ryosuke Takahashi’s rip-roaring account of his anime career, in which he described his flight from the Japanese animation business as it collapsed in the early 1970s.

“I wasn’t there. I’d fallen in with Juro Kara, a playwright who’d briefly worked at Mushi Production as a scriptwriter. But whenever Tezuka asked him to change something, he would just glare back at him, and after a while, I think Tezuka was scared of him.

“Anyway, Kara and his wife were also avant-garde theatre performers, and they would be onstage with a bunch of dancers, painted gold. After the show, they would all jump in the bath together and scrub each other down naked, to get all the paint off. I realised that if I joined the troupe, I would have to jump in the bath with all the actresses. So I volunteered for that and ended up on a European tour…”

This is the very same Juro Kara theatre troupe that Buruma runs into in Tokyo, whose output he describes as: “Songs, or zany references to popular movies, manga characters, TV commercials, political scandals, and even snatches of French existentialism alternated with scenes of pure slapstick.” I like to think that a young Ryosuke Takahashi was cavorting somewhere in the middle of all that, painted gold, and rubbing against a bunch of naked actresses. Later in the book, Buruma falls in with Kara’s troupe, and hears stories of their disastrous overseas tour, which included a performance at a Palestinian refugee camp, where the baddie dressed up as an Israeli general and the audience threw stones at him. Admit it… you really want to read Ryosuke Takahashi’s memoirs now.

Halfway into the book, I wondered where it was going. There didn’t seem to be any over-riding direction, just endless drunken nights with B-list celebrities, gushing about how good he is with chopsticks. In a triumph of bathos to rival the best of Alan Partridge, Buruma spends all day getting made up and fitted for a walk-on role as a Jesuit missionary in Akira Kurosawa’s Kagemusha (pictured), only for the role to go to someone else. He translates Juro Kara’s play Mask of a Virgin, but fails to find a publisher. His failures snowball into almost-comical non-achievement.

Halfway into the book, I wondered where it was going. There didn’t seem to be any over-riding direction, just endless drunken nights with B-list celebrities, gushing about how good he is with chopsticks. In a triumph of bathos to rival the best of Alan Partridge, Buruma spends all day getting made up and fitted for a walk-on role as a Jesuit missionary in Akira Kurosawa’s Kagemusha (pictured), only for the role to go to someone else. He translates Juro Kara’s play Mask of a Virgin, but fails to find a publisher. His failures snowball into almost-comical non-achievement.

But no, that couldn’t be right. Ian Buruma is a fantastic author – I’ve read several of his books, which he barely mentions here. He alludes to documentaries he happened to make, but their production whisks by in barely a paragraph. It’s almost as if he hopes here to concentrate solely on “the nobility of failure”, preferring not to focus on his successes, but upon the daily grind of being a nobody in a distant land – a purgatory of bit-parts and walk-ons, anecdotes about famous people he runs into in bars, and endless stories about being treated like a talking poodle because he’s made the effort to learn Japanese.

The closest thing to an actual narrative comes through Buruma’s association with Kara’s theatre, his performance in an awful-sounding play called Tale of the Unicorn, and accompanying Kara to New York on a junket, where both he and Kara come to realisations about their respective futures. In that regard, A Tokyo Romance is an answer to, and echo of, and companion to John Nathan’s Living Carelessly in Tokyo and Elsewhere, which is similarly an account of years perhaps wasted as an also-ran – a talent squandered in translation, journalism and belles-lettres, making others look good, even if they don’t really deserve it.

Soon enough, Buruma realises that he needs to get out before it ruins him. “I didn’t want to spend all my working life explaining Japan,” he confesses, as he works through his decision to leave it all behind. “The constant explainer runs the risk of never learning, and becoming a bore.”

Jonathan Clements is the author of An Armchair Traveller’s History of Tokyo. He has never been to a gay orgy with Donald Richie.

Leave a Reply