Books: Anime Supremacy!

June 9, 2018 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

Anime Supremacy!, a translated Japanese novel published by Vertical, takes on the real-life side of the anime industry, more frantic and quirky than any 2D antics. The author, Mizuki Tsujimura, is not an anime pro, which would seem to reduce the book’s interest greatly. But wait! The last pages have an impressive list of the people Tsujimara interviewed while researching her novel. The roll-call includes Kunihiko Ikuhara, creator of Utena; Genki Kawamura, producer of Your Name, Fireworks and The Boy and the Beast; and Katsuji Morishita, a Prodution I.G producer who’s handled everything from Dead Leaves to xxxHOLIC.

Anime Supremacy!, a translated Japanese novel published by Vertical, takes on the real-life side of the anime industry, more frantic and quirky than any 2D antics. The author, Mizuki Tsujimura, is not an anime pro, which would seem to reduce the book’s interest greatly. But wait! The last pages have an impressive list of the people Tsujimara interviewed while researching her novel. The roll-call includes Kunihiko Ikuhara, creator of Utena; Genki Kawamura, producer of Your Name, Fireworks and The Boy and the Beast; and Katsuji Morishita, a Prodution I.G producer who’s handled everything from Dead Leaves to xxxHOLIC.

Notably, the author interviewed several high-placed women, including Rie Matsumoto, director of Blood Blockade Battlefront; Keiko Matsushita, producer of A Letter to Momo and Miss Hokusai; and Hitomi Hasegawa, whose animation director credits include HAL and several Attack on Titan episodes. Women may still be under-represented in anime, but they’re making gains: think of A Silent Voice, which had a woman director, Naoko Yamada (K-ON!), and the scriptwriter Reiko Yoshida, who also wrote Lu Over the Wall.

Anime Supremacy! reflects this, being told through the eyes of three women in anime. One’s a producer, one a director and one an animator, and the book tells each of their overlapping stories in turn. The women work in TV, and Anime Supremacy! focuses on one season – the three-month period in which new shows fight for attention in the niche market. This is not primarily a fight for renewal, for more episodes. Many of today’s anime are designed to run for no more than a dozen episodes. Instead, the fight is for DVD and toy sales… and, for sentimental pros who think of more than numbers, the fight is for their shows to be remembered by viewers, like the Heidis and Gundams before them.

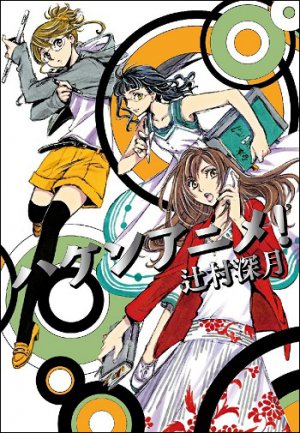

The women (who look very different on the original Japanese cover, right) are involved in two rival TV shows, both imaginary. One is a mecha series, the other a magic girl show. The book isn’t about the specifics of these imagined series, though they’re well-enough described. The best compliment is that their premises sound interesting enough that they could be real. The magic girl show starts with the heroines as grade schoolers, with each successive episode set a year after the last, showing them growing up week on week. The mecha show has a robot which can absorb particular sounds from the world, with devastating consequences for one of the youngsters who rides it.

The women (who look very different on the original Japanese cover, right) are involved in two rival TV shows, both imaginary. One is a mecha series, the other a magic girl show. The book isn’t about the specifics of these imagined series, though they’re well-enough described. The best compliment is that their premises sound interesting enough that they could be real. The magic girl show starts with the heroines as grade schoolers, with each successive episode set a year after the last, showing them growing up week on week. The mecha show has a robot which can absorb particular sounds from the world, with devastating consequences for one of the youngsters who rides it.

Kayoko is the producer of the magic girl show. Her main job is coping with the show’s prima donna male creator, Oji, who’s insisted on writing and directing it. Now there’s a crisis; Oji has vanished off the face of the earth, having only delivered the early episodes. Kayoko faces the hideous prospect of breaking the news to the parties involved with the eagerly-awaited show, but she can’t bear to do it. So she fights to keep a confident front in her everyday dealings – with surly animators, with the partner company handling the figurines, with the industry rivals she meets by accident – while she’s melting down inside.

The second storyline also deals with the producer-director relation, at another studio from the opposite side. Hitomi is director of the season’s mecha series, who’s having issues with recalcitrant voice-actors and the aggressive promotion strategies of her (male) producer.

Then the third segment focuses on Kazuna, a nerdy, gifted animator at a studio in the Japanese boonies, working on both Kayoko’s and Hitomi’s series. Kazuna’s story brings in the phenomenon of holy lands; that’s when an anime is set in a real place that becomes a mecca for fans.

A couple of the novel’s based-on-fact elements are transparent. The director Hitomi works at Tokei Animation, described as an “industry behemoth” and a “venerable institution”. That’s obviously Toei animation, the oldest and largest anime studio. The novel mentions that many great anime talents start at To(k)ei, then move elsewhere, which was true for Miyazaki, Takahata, Hosoda, and others. The real Toei makes anime of many of the most enduring franchises: Dragon Ball, Sailor Moon, Digimon, PreCure and a little show called One Piece.

As the novel acknowledges, To(k)ei has a particular track-record in making magic girl series (a form Toei instigated with Little Witch Sally in 1966). In the novel, this ties in with the backstory of Oji, who’s said to have started out at “Tokei” making a ground-breaking magic girl series. From the book: “The façade of his magic girl anime may seem to suggest children’s programming, but the actual content could be quite violent and mature… Oji’s anime had been widely lauded for showing the often painful coming-of-age process for teenage girls vividly and honestly.”

This description might nod to a Toei magic girl show like Sailor Moon (at least on some measures of “violent” and “mature”). However, it’s hard not to think it’s really referencing a far more recent series, Puella Magi Madoka Magica. Madoka wasn’t made by To(k)ei, but that’s the fun of fictionalising!

This description might nod to a Toei magic girl show like Sailor Moon (at least on some measures of “violent” and “mature”). However, it’s hard not to think it’s really referencing a far more recent series, Puella Magi Madoka Magica. Madoka wasn’t made by To(k)ei, but that’s the fun of fictionalising!

As for the tempestuous relationship between the patiently suffering producer Kayoko and the immature, infuriating, genius-creator Oji… Well, perhaps it’s hinting towards a well-known partnership at another studio, Ghibli. However, it’s hard to imagine Miyazaki standing up for “otaku”, as Oji does in the book’s most impassioned speech.

For any reader interested in the workings of the anime industry in Japan, there’s plenty of meat in Supremacy! One of the best scenes involves a mini-crisis when Hitomi’s mecha show is being featured on a magazine cover. It turns out that the art for the cover – which has to be an exclusive, original image – didn’t go through proper checks because of the tight schedule, and the image is terrible. The producer’s response is to get the mobile number of the show’s best animator, who’s the freelancer Kazuna. She’s on holiday, on a long-awaited romantic date in Tokyo, but that doesn’t matter; the producer calls her and tells her to come in to the office now to draw the picture.

In an inspired touch, this scene is described twice, from the perspectives of Hitomi and Kazuna in their respective narratives. It’s a great illustration of anime’s interdependent talents, the book stressing there are no one-man-bands. Even the prima donna creator Oji confesses, “If I don’t ask other people to help me, the project won’t move ahead… I’m being entrusted with a big chunk of everybody’s lives, for the sole purpose of giving shape to something I want to create.”

Kazuna, the animator, makes comparable comments about her talents. In the novel, her scenes in Hitomi’s series are picked out by fans, who call them “god genga.” (The book uses the words genga and doga for what we would call “key animation” and “in-betweens.”) Kazuna, though, argues her drawings “should never be looked at as works of art that can stand on their own. And when people see some value in an individual drawing, that’s entirely true to the charm and appeal of the overall creation.”

We don’t know if this is the author’s own view, or that of one or more professionals she interviewed. Either way it’s notable, given that some western “sakuga” evangelists seems to push for the reverse view – that anime’s art lies in individual bursts of brilliant drawing, seconds here and there, breaking out of the production line.

Oji, though, makes an interesting comment to muddy the waters. “Some fans will love (my anime) even more than I do… It belongs to whoever devotes the most affection to it.” This could be saying that everyone can be right about anime. Or maybe it’s saying that the true fans are those who shout loudest and longest about why Kemono Friends rules or why (outside anime) Last Jedi sucks.

Beyond Anime Supremacy!’s information about the industry, it’s an enjoyable read… for its first three-quarters. The prose (translated by Deborah Boliver Boehm) is workmanlike, with enough hackneyed phrases to drive off literateurs, but it’s a good story, making you consider characters in contrasting lights. For anyone wondering, the novel doesn’t really touch on sexism in the industry; only a few glancing references, like some puerile comments by the man-child Oji, and Hitomi suffering interviews “that try to frame her work as a ‘woman’s’ in a facile manner.” Maybe that whistle will be finally blown in 2027.

Beyond Anime Supremacy!’s information about the industry, it’s an enjoyable read… for its first three-quarters. The prose (translated by Deborah Boliver Boehm) is workmanlike, with enough hackneyed phrases to drive off literateurs, but it’s a good story, making you consider characters in contrasting lights. For anyone wondering, the novel doesn’t really touch on sexism in the industry; only a few glancing references, like some puerile comments by the man-child Oji, and Hitomi suffering interviews “that try to frame her work as a ‘woman’s’ in a facile manner.” Maybe that whistle will be finally blown in 2027.

Still, the segment about the woman animator, Kazuna, is gently pointed in a different way. The Tokyo-born Kazuna has to accompany a small-town employee around a countryside region that’ll be touted as an anime “holy land,” and getting more and more annoyed at his ignorance of fan perspectives. For example, he doesn’t realise it would be tacky to put life-size character cut-outs in a cave; “What anime fans see won’t be the actual place, but the landscape inside their heads.”

Finally, though, Kazuna realises that her own perspective is just as limited, in a plot strand that plays increasingly as a riff on the country scenes in Takahata’s Only Yesterday. In particular, the book suggests an interesting analogy between the otaku subculture and rural subcultures; they’re both small spheres of people, knowledge and mutual support.

The 400-page novel runs a good hundred pages too long at the end, after the interesting issues have been dealt with and the character disputes resolved. Still there’s one good late payoff, regarding the question of which series finally “triumphs” in the TV season. This is linked to the question of endings in TV anime. In the book, one of the creators deliberately doesn’t tie up a series in the way fans want, which has an impact on DVD sales.

Regarding the title, “Anime Supremacy” is described in the book as “an unofficial title to designate the most successful title among the many created in a given anime season.” The novel claims that “anime supremacy” is often used by both fans and professionals in Japan; I don’t know if that’s true or if it’s a dramatic device of the author. For the record, some of history’s greatest anime were commercial underperformers when they debuted in Japan.

Given the whole book focuses on TV anime, a couple of elements seem questionable. The book was written in 2014 and apparently set then, but it claims that nine years earlier – that is, in 2005 – the “predominant time slot for anime series wasn’t late at night” but rather at six p.m. in Japan. This is an enormous anachronism. By 2005, most anime TV shows were already being screened in late-night slots, to be seen only by night owls and TiVos.

Moreover, Hitomi’s mecha series in the novel – an original, self-contained series that appeals to children and older viewers – is supposedly made for early Saturday evenings. Such a show may not be impossible, but it would seem very unrepresentative of anime in 2014. A decade earlier, it wouldn’t be as odd. The first Fullmetal Alchemist anime played in early evenings in 2003-4, and Eureka 7 played on Sunday mornings in 2005-6. But by the 2010s, “primetime” anime was very largely dominated by kids’ shows and Shonen Jump-style franchises like Boruto, My Hero Academia and the new Black Clover.

In short, it looks like Anime Supremacy!, for all its insider insights, falls into the same trap as so much anime commentary, from East or West. It presents anime as far more mainstream in Japan that it actually is. Still, miracles can happen. If a quirky anime film by obscure director Makoto Shinkai can win “supremacy” at Japan’s all-time box office, then maybe TV anime can climb out of the margins. The first question, though, is whether mainstream TV anime should have mecha, or magic girls?

NB: The novel has a passing reference to an anime company called Studio Milky Candy. Unfortunately, we don’t know if it produced that great anime milestone, Schoolgirl Milky Crisis…

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films.

Leave a Reply