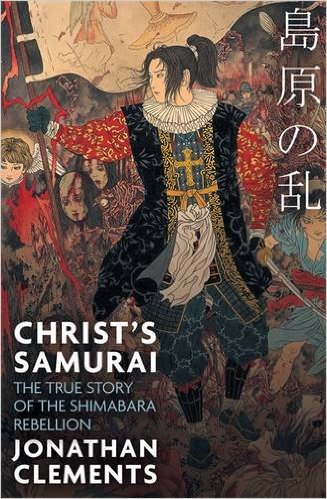

Books: Christ’s Samurai

April 12, 2016 · 0 comments

Andrew Osmond on the true story of the Shimabara Rebellion.

Christ’s Samurai by Jonathan Clements tells two stories, one enfolded within the other. The broader story is that of Christianity in Japan, beginning with the first missionaries to the country in the sixteenth century, their early success in winning converts (especially on the southern Japanese island of Kyushu), and then a backlash of persecution, purges and executions that turned Christianity into a secret religion, practiced at the risk of death.

Christ’s Samurai by Jonathan Clements tells two stories, one enfolded within the other. The broader story is that of Christianity in Japan, beginning with the first missionaries to the country in the sixteenth century, their early success in winning converts (especially on the southern Japanese island of Kyushu), and then a backlash of persecution, purges and executions that turned Christianity into a secret religion, practiced at the risk of death.

This story may gain broader mainstream attention in 2016 with the release of Martin Scorsese’s film Silence, based on a Japanese novel by Shusaku Endo and featuring Liam Neeson and Andrew Garfield as Jesuit missionaries. Whether it will change prevalent “liberal” attitudes is less clear. A news story about the Scorsese film on the Guardian website had several under-the-line commenters suggesting – with various degrees of nuance – that Japan’s violent suppression of Christianity was anti-colonial payback for Christianity’s atrocities elsewhere, as if the samurai beheading priests, their wives and children were somehow following the future teachings of, say, Noam Chomsky. One of the most chilling comments under the Guardian article read, “Japan should be grateful it cut out the tumour [Christians] before it destroyed their culture” – perhaps just weeaboo idiocy, or a warning that nothing changes.

As Clements points out in his measured account, the early missionaries in Japan weren’t thinking in terms of crusades or conquest. At the risk of using anachronistic terms, one might say their strategy was like the modern notion of soft power. “The missionaries were prepared to play a long game (in Japan),” Clements writes, “concentrating on the rich and powerful, in the hope that celebrity converts would drag many lesser members of society with them.”

The missionaries were hampered by their alien appearance in a country where very few Westerners had set foot. To the sixteenth-century Japanese, the missionaries looked grotesquely tall and long-nosed, and were often compared to tengu demons. And yet, the foreigners persevered and won converts, especially in the area around Nagasaki. The hawkish business of forced conversion was left to the first Japanese Christians, such as Lord Bartholomew of Omura, who “became such an enthusiastic convert to Christianity that he ordered anyone who did not similarly want to accept baptism to leave his domain immediately.”

Very soon, an enclave of Christian power was carved out in Kyushu, with Nagasaki at one end and Oyano, an island, on the other. One of the main figures of the time was an Italian Jesuit, Alessandro Valignano, whose achievements were remarkable. Thanks to the converted Bartholomew, he was the behind-the-scenes master of Nagasaki. Valignano also scored a PR coup by sending Japanese emissaries on an epic journey to the Vatican, where they met a dying Pope, attended his successor’s coronation, and returned to Japan with a printing press.

Very soon, an enclave of Christian power was carved out in Kyushu, with Nagasaki at one end and Oyano, an island, on the other. One of the main figures of the time was an Italian Jesuit, Alessandro Valignano, whose achievements were remarkable. Thanks to the converted Bartholomew, he was the behind-the-scenes master of Nagasaki. Valignano also scored a PR coup by sending Japanese emissaries on an epic journey to the Vatican, where they met a dying Pope, attended his successor’s coronation, and returned to Japan with a printing press.

But Valignano knew these successes could be snatched away. His great fear, Clements writes, was that “other Europeans would regard the Japanese with the same kind of condescension that had led the Spanish to annex great tracts of other heathen lands… Although he and his associates enjoyed high favour with many of the leaders of the southern provinces, he only enjoyed their support as a religious man. If politics ever got involved, or, God forbid, the military, Valignano predicted a terrible backlash.”

In fact, there were a series of backlashes, exacerbated by massive political upheavals in Japan. Some of Japan’s most powerful lords, finding Christian teachings incomprehensible, saw them only as political threats. The situation may have been worsened by an incident in 1596, when the San Felipe, a Spanish ship, was wrecked off Shikoku and arguments broke out over the salvaged cargo.

According to one account, the ship’s pilot tried to brazen it out to the local samurai, “by boasting of the immense power of the Spanish king, the uncountable troops of the Spanish imperial armies, and Spain’s manifest destiny to conquer the world… In a fatal, disastrous flourish, the pilot added that the front lines of any Spanish conquest were the missionaries who arrived first, preaching a message of peace, but all the while steering the will of the next generation to accept Christian Spain as its lord and master.”

It’s easy to see modern parallels with, for example, the incendiary rhetoric of headline-making groups like Islam4UK. A year after the San Felipe incident, twenty-six Catholics were crucified in Nagasaki. The crucifixions were ordered by the pre-eminent lord Hideyoshi, who died soon after, but what followed would be worse. From the power-struggle after Hideyoshi emerged a new Japan, unified as never before under the Tokugawa Shogunate. This would rule the country for two and a half centuries, sealing it almost completely from the outside world. And it aimed to purge Japanese Christians from existence.

In 1614, Christianity was decreed a “pernicious doctrine.” All foreigners (along with their mixed-race children) were told to leave the country, excepting only Dutch merchants, who were confined to tiny ghettoes in the Nagasaki area. Clements writes, “Brandings and mutilations of Christians continued throughout the decade, as the cult refused to die. The stories are often horrific, many of them tragic, but just as believers took constant heart from the many martyrdoms, their persecutors became increasingly unsettled by the sheer conviction of their victims.”

In 1614, Christianity was decreed a “pernicious doctrine.” All foreigners (along with their mixed-race children) were told to leave the country, excepting only Dutch merchants, who were confined to tiny ghettoes in the Nagasaki area. Clements writes, “Brandings and mutilations of Christians continued throughout the decade, as the cult refused to die. The stories are often horrific, many of them tragic, but just as believers took constant heart from the many martyrdoms, their persecutors became increasingly unsettled by the sheer conviction of their victims.”

Japanese missionaries must have felt they were following the persecuted tradition of the first Christians. Instead of Rome’s Circus, they faced pools of boiling sulphur, as they were martyred in the boiling lakes of Mount Unzen. Not all the anti-Christian measures were so monstrous. For example, it became standard procedure to order believers to renounce their faith by stepping on an image of Mary or a saint. For the Protestant Dutch merchants, this was no problem; but many Catholics proudly refused, even if it meant their torture and death.

The Japanese found this incomprehensible, much, perhaps, as modern secularists are baffled by suicide bombers. Clements describes the order to Christians to deface an image in terms of “that most Japanese of gestures, a white lie to save face with the majority, and government officials were mystified if Christians refused to do it. They were also a little scared, as refusal implied that the Christians truly did recognise and serve a higher power than the Shogun. What if, some reasoned, that same power ordered them not to die for their faith, but to fight for it?”

It is in this context that Clements places the second of the book’s stories – though it’s sometimes an enigmatic blur, a historical mystery, that’s given rise to many stories, most of them doubtful. From late 1637 to spring 1638, there was an uprising in Kyushu, involving tens of thousands of people, which is now generally named the Shimabara Rebellion. In many of the official records, it was linked to Christianity – certainly many of the people fighting the Rebellion saw it as such. But it may have been more of a Japanese peasants’ revolt, occurring in a region mercilessly taxed to the point of starvation.

It is in this context that Clements places the second of the book’s stories – though it’s sometimes an enigmatic blur, a historical mystery, that’s given rise to many stories, most of them doubtful. From late 1637 to spring 1638, there was an uprising in Kyushu, involving tens of thousands of people, which is now generally named the Shimabara Rebellion. In many of the official records, it was linked to Christianity – certainly many of the people fighting the Rebellion saw it as such. But it may have been more of a Japanese peasants’ revolt, occurring in a region mercilessly taxed to the point of starvation.

It wasn’t just the peasants who suffered. On some accounts, one official targeted a wealthy land-owner over a trivial debt, seizing his pregnant daughter-in-law and locking her in a flooded cell to freeze to death. Unfortunately for the authorities, the farmers weren’t just peasants. Many of the older ones had been involved in the battles that brought the Tokugawa Shogunate to power. They still had comrades, and some still had arms – including muskets, despite state efforts to ban the foreign weapons.

And they had a hero, a Japanese Christian guru called Jerome Amakusa. Clements picks his way through the legends, stressing how little we know of Jerome with any certainty. According to some accounts, he was a strikingly beautiful teenage boy, “an eerie, white-robed child messiah.” Other sources claim he was deformed by a skin disease. His image was conflated with the Portuguese boy-king Sebastian I of the previous century, whose story had been celebrated by the Japanese missionaries. In today’s media, Jerome is portrayed in Japanese films, rock musicals and videogames. He may also be an inspiration for the figure of Griffith in the Berserk saga by Kentaro Miura.

Historically, it’s uncertain if Jerome was a true leader, a figurehead installed by the revolt’s real leaders, or something between. Many details of the rebels are fuzzy, yet, their achievements were substantial. They won several battles and gained ground in Kyushu, helped by blunders on the part of the authorities in a country that was far from being a cohesive nation. It could take three weeks for a messenger to travel from the area of trouble to the seat of Japanese government and back again. Local lords on the ground dismissed the rebel threat as “a crowd of angry villagers with picks and hoes” and would pay dearly.

While Clements debunks many of the more lurid stories – such as suggestions there were ninja lurking among Jerome’s ranks – some of the most remarkable developments in the Rebellion are backed by the records. For example, the Rebellion could be seen as a movement driven by alien, un-Japanese influences…Yet the samurai lords fighting it commandeered the help of the Dutch community, still locked down in Nagasaki. The result was Dutch Protestants lending their firepower to a war on Japanese Catholic converts, although their help was limited and could literally backfire.

Later, there were extraordinary developments involving a traitor in Jerome’s ranks, and a samurai “army” so divided and competitive that on their day of glory, they may have been as keen to kill each other as the enemy. The final part of the Rebellion reads as an extraordinary action film, a desperate last stand with Jerome’s hundreds of followers confined to a castle, raining down everything from fire arrows to excrement on the samurai. Readers should be warned, though, that the story has a devastatingly bleak ending. This was a battle of annihilation, “a genocide against fellow Japanese, all to create a Japan that could claim a unity of belief and purpose.”

Later, there were extraordinary developments involving a traitor in Jerome’s ranks, and a samurai “army” so divided and competitive that on their day of glory, they may have been as keen to kill each other as the enemy. The final part of the Rebellion reads as an extraordinary action film, a desperate last stand with Jerome’s hundreds of followers confined to a castle, raining down everything from fire arrows to excrement on the samurai. Readers should be warned, though, that the story has a devastatingly bleak ending. This was a battle of annihilation, “a genocide against fellow Japanese, all to create a Japan that could claim a unity of belief and purpose.”

The last pages of Clements’ book serve as a coda, returning to the wider story of Christianity in Japan. If anything, the history of the religion after Jerome’s rebellion is more amazing than the rebellion itself. Christianity was reduced to the most secret and perilous of cults, the Hidden Christians or “Kakure Kirishitan” of remote farms and fishing villages. Their iconography adapted to a situation where discovery could mean slaughter. “The Kirishitan would form a cross made of coins on the floor – a symbol that could be removed with a sweep of the hand.”

With the sacred texts gone, Japanese Christianity was transmitted by word of mouth, leading to mutations of the holy word. One nineteenth-century Japanese Bible gives King Herod two henchmen, Pontia and Pilate. Another “Hidden Christian” cell claimed that Jesus had a teacher named Sacrament, while Judas – who had more than one fate in the Bible already – was turned into a tengu for his betrayal.

This underground cult survived into the mid-nineteenth century. It was ended not by a purge but by Japan’s opening to the world, and the end of the Tokugawa Shogunate. Clements recounts the story of an astonished bishop, permitted to minister to the foreigners in Nagasaki, who was greeted by Japanese people joyfully identifying themselves as Christian. Many hundreds of Japanese Christians were posthumously beatified and canonised by the Catholic church, though that did not extend to Jerome and his rebels, partly because saints are not meant to offer resistance.

It is hard to read even this as a happy ending. The faithful were still centred around Nagasaki in 1945, when the atom bomb killed three-quarters of the city’s Christians. Today, Christianity is a vanishingly small minority faith in Japan, yet with a unique legacy in the country’s history. For the secular reader, the Christians who endured such merciless persecution may be as alien to us now as they were to the Japanese themselves when the missionaries first came ashore. As Clements reflects, “there is an insurmountable distance between our superficial modern selves and the fervent, heartfelt resilience of the martyrs of the historical record.”

Christ’s Samurai: The True Story of the Shimabara Rebellion is out now in paperback and on the Kindle (UK/US).

Leave a Reply