Books: Leiji Matsumoto

January 25, 2021 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

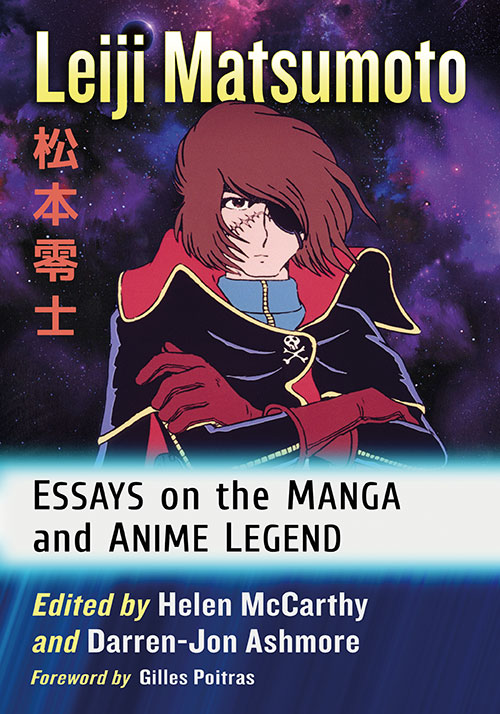

For all the passion and excitement that the contributors bring to the new collection Leiji Matsumoto: Essays on the Anime and Manga Legend, their subject can be a tough sell. That’s not to say that he isn’t one of the top creators in the anime and manga world, and a hugely influential figure in the 1960s and 1970s. An English-language book on his life and work is, as editors Helen McCarthy and Darren-Jon Ashmore note, long overdue, and several of the essays in this volume make clear just how big a deal he really is.

But Leiji Matsumoto’s work doesn’t lend itself well to concise summary. Several massive, sprawling, internally contradictory serials feature reincarnations and doppelgangers of the same basic cast. The same story is retold a dozen times, with different whistles and bells on an iconic spaceship. Massive chunks of his manga output remain untranslated, and he arguably has a greater media footprint in the French-speaking world than in English. Like several other major franchises among the anime classics, we might even say that some of his landmark works are really known more by reputation than direct experience – how many people do you know who have actually seen every episode of any one of his best-known anime creations? Space Cruiser Yamato has its American followers d’un certain age, one of the most prominent of which, Tim Eldred, is a contributor to this volume. But hardly anyone in the English-speaking world except Helen McCarthy herself has sat through all of Captain Harlock, and as for Galaxy Express 999, I can count on one hand the people I know who have even seen it.

The aforementioned Tim Eldred is not merely a Matsumoto super-fan, but an artist in his own right, who has spent a lifetime deconstructing Matsumoto’s manga. Having literally been paid to pastiche and adapt Matsumoto’s work in comics of his own, Eldred offers an insightful breakdown of everything from panel composition to framing devices. Similarly, Matsumoto’s translator, Zack Davisson, dives deep into the poetry within Matsumoto’s writing, unpicking the simple phrase “I am Emeraldas,” but venturing ever further into his work. In a lovely and illuminating touch, Davisson challenges the acclaimed academic Jay Rubin to a “translation battle”, and the two of them each deliver their own version on the same speech from a Matsumoto manga.

Stefanie Thomas entertainingly trains a feminist lens on Matsumoto’s heroines, asking to what extent these queens of the space age are actually trapped in time, unable to leave the attitudes and assumptions of the patriarchal 1970s. Meanwhile, Edmund Hoff, supposedly investigating the world of costuming, actually smuggles in an overview of materials available for investigating the history of Japanese fandom. Because while I might cheekily suggest that Space Cruiser Yamato is “obscure” to the average UK millennial fan today, any anime historian has to concede that it was the sci-fi blockbuster of the early 1970s in Japan, attracting a legion of devotees. When it comes to fandom, as Hoff notes, this was not merely a case of who dressed up as a space pirate in a hotel ballroom, but a more contentious issue of the 1980 “civil war” that played out in conventions between horrified fans of prose SF and an invading horde of anime weebs. Japanese SF fandom was never the same again; just ask Gainax.

Jonathan Tarbox writes an account of Matsumoto’s The Cockpit, which at first seems to be just about to break new ground by delving into the untranslated nine-volume manga series, but eventually scales back its coverage to the three stories contained in the anime adaptation. This, supposedly, is because they were regarded by Matsumoto himself as the essence of the whole series, but despite illustrations dropped in from the manga, Tarbox gives every appearance of only describing the anime. He even recounts the last line of “Slipstream” in which a German pilot, saving Europe from an A-Bomb, boasts that he did not sell his soul to the Devil. As the translator of the UK release, I happen to know that line was not in the original script, but was scrawled into my copy in ballpoint pen, a last-minute addition in the recording studio. Is Tarbox telling us that line was in the manga, or is he simply hearing it on the anime soundtrack?

Darren-Jon Ashmore finishes off the book with a 12-page interview with the man himself, sure to be mined by others in search of foundations for their own work on the subject. Matsumoto holds forth on all sorts of odd subjects, including several of his media inspirations, the possibility that Disney animators did the special-effects work on Gone with the Wind, and that time that he and Osamu Tezuka were dragged in for police questioning. They had been sneaking around at night with film projectors and materials, in order to put in extra hours on the first cut of Astro Boy, and the authorities had mistaken their nocturnal scurrying for a pair of spivs setting up an unlicensed cinema.

We make a habit on this blog of price-shaming publishers who want to charge the Earth, so credit where credit is due: I can forgive a lot in a book that can be had for a cheap and cheerful £17. Such a bargain makes me less likely to gripe for all that long about an editorial policy towards Japanese spelling that seems to change from chapter to chapter, or some contributors’ occasional tendency to ramble on like drunken uncles. This book doesn’t claim to be the be-all and end-all of Matsumoto scholarship; instead, its cover boasts the incredibly modest promise of nothing more than some essays. It does not set itself standards that it cannot deliver.

When it comes to Matsumoto, this book is a good place to start. In addition to its wide-ranging collection of essays (did we really need two on cosplay?), and introductions to both Matsumoto the man and his themes by the two editors, it has the aforementioned highlights and a chunky bibliography of Matsumoto’s published and produced works. It’s less satisfactory, however, in its marshalling of secondary material; the editors begin by announcing that remarkably little has been written about Matsumoto in English, but do not bother to point the reader at some of the most pertinent work that actually has been. There is a revealing interview with Matsumoto, for example, about his youth illustrating girls’ comics, in Masami Toku’s International Perspectives on Shojo, but the contributors ignore it, despite including a reference to an interview in the same volume with his wife, Miyako Maki; nor would anyone reading this book be informed that they could read a story from The Cockpit in Frederik L. Schodt’s Manga! Manga!. The introduction is also off-handedly dismissive of Japanese sources, mentioning that there are a few “contradictions” to be found. That’s as maybe, but Osamu Takeuchi’s bibliography of anime and manga scholarship lists five pages of closely-printed, small-font references for Japanese works about Matsumoto, few of which seem to have made it onto the contributors’ reading lists. They can’t all be awful, can they…?

When putting out a call for papers, particularly for a book that does not carry the cultural capital of being published by a university press, beggars can’t be choosers. If I were drawing up an editorial wish-list on Matsumoto, I would probably hope for something on his Francophone footprint (including Daft Punk), and something else specifically on his non-sf works. Considering the amount of ink spilled in Japanese over his long spat with Yoshinobu Nishizaki, it would have been nice to have seen something specifically on the legal battle over who got to flog the never-quite-dead horse of the Yamato franchise, but those aren’t the people who showed up for this project, so you get what you’re given. The editors’ stated aim is to inspire others to fill in those gaps themselves in other venues – they have provided such future scholars with a reasonable starter kit.

“Our aim” they write in their introduction, “is to open the door and reveal a little of what lies beyond, in the hope that others will follow the path and explore further.”

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History. Leiji Matsumoto: Essays on the Anime and Manga Legend is published by McFarland.

Leave a Reply