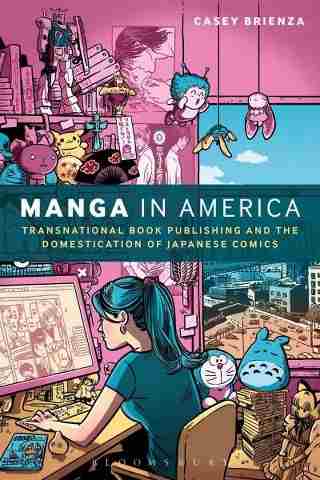

Books: Manga in America

January 28, 2016 · 0 comments

Jonathan Clements on the bistromathics of manga.

Casey Brienza’s Manga in America: Transnational Book Publishing and the Domestication of Japanese Comics reveals an ultra-modern publishing industry, exploiting the bleeding edge of digital ingestion and yet staffed by scattered freelance peons, some of whom literally sift through dumpsters for their dinner. Or is it, perhaps, a consensual hallucination of Cool Japan, which is actually “little more than ad copy to allow public funds to go to advertising companies”? Anonymous interviewees pack her pages as she tracks down everybody from the bloviating big boss to the over-worked, under-appreciated translator in pyjamas. The picture she paints is of a business in constant crisis, where, to steal a phrase, nobody knows anything.

Casey Brienza’s Manga in America: Transnational Book Publishing and the Domestication of Japanese Comics reveals an ultra-modern publishing industry, exploiting the bleeding edge of digital ingestion and yet staffed by scattered freelance peons, some of whom literally sift through dumpsters for their dinner. Or is it, perhaps, a consensual hallucination of Cool Japan, which is actually “little more than ad copy to allow public funds to go to advertising companies”? Anonymous interviewees pack her pages as she tracks down everybody from the bloviating big boss to the over-worked, under-appreciated translator in pyjamas. The picture she paints is of a business in constant crisis, where, to steal a phrase, nobody knows anything.

Brienza acknowledges the awful poison at the heart of the American manga industry, which is that it was colonised some 15 years ago by snake-oil salesmen and carpet-baggers determined to slap the word manga on anything that they did, out of a cynical desire to clamber aboard a bandwagon that promised, at the time, “double-digit growth.” As I have pointed out on many previous occasions, this didn’t just confuse everybody as to what manga actually was, but also corrupted much of the available data. A manga is a Japanese comic, anybody who says otherwise is selling something.

Brienza admits her frustration with this issue, although inevitably some of her sources are those self-same opportunists, still prepared to glibly insist that any comic is a “manga” if the characters have big eyes, or there is a talking fox in it, or that has “attitude”, or any such number of sad little tropes, none of which relates directly to comics from Japan or drawn by Japanese people. As a result, in spite of her attempts to establish firm ground-rules and diligent approaches to data and research, her account of the American domestication of Japanese comics occasionally struggles to maintain its focus, as if a child is constantly dragging her by the hand, demanding that she pause to praise the colouring-in on someone’s big-eyed vampire strip. This begins with one of the first statistics she offers: a financial estimate of the size of the American manga business, from an organisation that sometimes counts manga, and sometimes counts American comics that claim to be manga, and sometimes counts American comics that merely contain Japanese subjects. Your guess is as good as mine as to what this ridiculously bistromathic number actually represents.

But Brienza struggles and succeeds. Despite a buffeting of lies and spin, she hangs onto her subject with white-knuckle resolve. She chooses her term “domestication” with immense and closely-argued care, pointing out that there is more to localising manga than mere translation, but also that publishing manga in America has had a deeper, cultural effect on the attitudes of Americans and Japanese to the product itself, and to each other. Manga, for Brienza, becomes a lens through which she examines a broader issue in publishing: the colonisation of the world of books by the world of comics.

The bulk of her research is concentrated on the 21st century. “Nobody has reliable data on total American manga sales prior to 2002,” she writes, “because among other things, suffice to say, it was not important enough to measure.” Brienza hence delineates a decade-long archive of accessible data and materials. This, however, exposes her to the mind-melting danger of the Tokyopop Reality Distortion Field, wherein a single, aggressive company crammed the publishing world with pile-’em-high, sell-’em-cheap comics, some of which were Japanese, some of which were not.

Tokyopop’s role was certainly influential, not the least in matters of memory, where it seems whoever shouts the loudest is the winner. Stu Levy, the flamboyant company founder, speaks perfect Japanese, which swiftly ingratiated him with Tokyo rights-holders swayed by the ease of communicating with him, regardless of what happened to their products further down the production chain. Brienza points to certain technical issues such as trim size, where the company made strides ahead of the competition that were invisible to the layman. But it is simply not true to say that Tokyopop’s retention of the Japanese right-to-left presentation was “unprecedented in the United States” – it was first done by Blast Books on Hideshi Hino’s Panorama of Hell in 1993, and my own translations of Takeshi Maekawa’s Ironfist Chinmi, similarly unflipped, were on sale from Del Rey in America from 1997. As Brienza notes, much of Tokyopop’s achievement was in its masterful, world-class management of hype, and occasionally such blather still seems to dominate the discourse. It’s not that I am hung up on “firsts” – Brienza’s arguments are still persuasive. It’s just that in spite of her diligence, sometimes the hype rubs off, like ink on your fingers from a grubby bargain-bin.

Tokyopop’s role was certainly influential, not the least in matters of memory, where it seems whoever shouts the loudest is the winner. Stu Levy, the flamboyant company founder, speaks perfect Japanese, which swiftly ingratiated him with Tokyo rights-holders swayed by the ease of communicating with him, regardless of what happened to their products further down the production chain. Brienza points to certain technical issues such as trim size, where the company made strides ahead of the competition that were invisible to the layman. But it is simply not true to say that Tokyopop’s retention of the Japanese right-to-left presentation was “unprecedented in the United States” – it was first done by Blast Books on Hideshi Hino’s Panorama of Hell in 1993, and my own translations of Takeshi Maekawa’s Ironfist Chinmi, similarly unflipped, were on sale from Del Rey in America from 1997. As Brienza notes, much of Tokyopop’s achievement was in its masterful, world-class management of hype, and occasionally such blather still seems to dominate the discourse. It’s not that I am hung up on “firsts” – Brienza’s arguments are still persuasive. It’s just that in spite of her diligence, sometimes the hype rubs off, like ink on your fingers from a grubby bargain-bin.

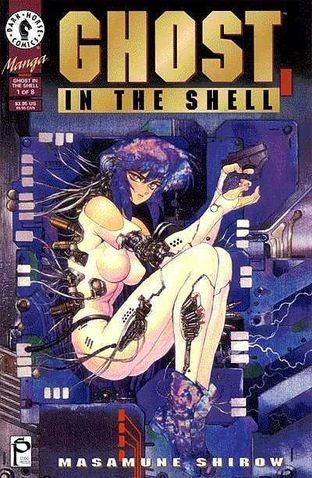

It saddens me, for example, that her account never quite appears to engage with the late Toren Smith – although some of the anguished accounts she quotes of dealing with the Japanese could easily be from him. In many ways, Smith was the greater fool with whom the new arrivals were contending; his approach with titles such as Ghost in the Shell was regarded by Tokyopop and their ilk as over-engineered. And yet, Ghost in the Shell is still in print. Smith saw manga as a field that required long-term husbandry, but his blue-chip, slow-burn approach was entirely swamped by an onslaught of what Brienza diplomatically calls “less labour intensive and expensive” publications, on cheaper paper with cut-rate translations and half-hearted retouch, which apparently made them “100% authentic” – Tokyopop’s words, not Brienza’s! When Smith died in 2013, I was shocked how many manga fans had never heard of him.

It saddens me, for example, that her account never quite appears to engage with the late Toren Smith – although some of the anguished accounts she quotes of dealing with the Japanese could easily be from him. In many ways, Smith was the greater fool with whom the new arrivals were contending; his approach with titles such as Ghost in the Shell was regarded by Tokyopop and their ilk as over-engineered. And yet, Ghost in the Shell is still in print. Smith saw manga as a field that required long-term husbandry, but his blue-chip, slow-burn approach was entirely swamped by an onslaught of what Brienza diplomatically calls “less labour intensive and expensive” publications, on cheaper paper with cut-rate translations and half-hearted retouch, which apparently made them “100% authentic” – Tokyopop’s words, not Brienza’s! When Smith died in 2013, I was shocked how many manga fans had never heard of him.

Nor does Brienza appear to have accessed the Japanese-language memoirs of Seiji Horibuchi, Smith’s occasional nemesis at Viz Communications and the self-styled midwife of manga in America. Viz Communications makes an appearance as part of the fervid competition with Tokyopop, but Brienza could have written a whole chapter on Horibuchi’s activities in the 1990s, before Tokyopop was a twinkle in Stu Levy’s eye. However, this is all quite understandable – these are not omissions but decisions. Brienza’s interest is in big-picture publishing, specifically as a mass-market industry rather than the artisanal fumblings of the pioneers, so it is unsurprising that she begins with Tokyopop (or Mixx, as it then was called) at the turn of the century, not so much for the company’s breathless self-regard, but for the happenstance in 2005 that saw its releases racked in bookshops rather than in comic stores. Founded on false equivalences, with apples traded as oranges, the American manga business slumped soon afterwards in 2007 – it took many years to recover.

Although Brienza asserts that “there would be no American manga industry without Tokyopop,” she is also ready to discuss many of the criticisms levelled at the company and its evangelist founder. The main body of her work discusses those who actually work in the manga business – the opportunists who want to shake down the consumers for money, say, or the sales specialists who realise that “buying an end cap display at Barnes & Noble sells more books than a full page ad in the New York Times Book Review.”

She is particularly good on the conflicts behind the scenes. There is an even-handed account of the tensions of bringing a manga creator to the US as a convention guest, told through both the frustrations of the organiser facing mountains of red tape, and the Japanese publisher who cannot afford the “damage” of giving his artist a one-week vacation from his 1.5 million expectant readers. Her horror stories of the bad boys among the Japanese rights-holders ring all too true, particularly in the case of a disdainful editor who seems to regard his job as an opportunity to avenge himself on America for imagined racist slurs. Where foreign sales are worth only 15% of the revenue for the Japanese manga business (compare to 10% in anime), Brienza points to a new field of arm-twisting: the insistence by manga publishers that American rights-buyers also take the original prose novels if they want the manga, creating an entire sub-set of fiction published in limited runs merely to satisfy a contractual clause.

Brienza’s wild ride through the noughties takes the manga business through its infamous slump, revealing on the way the dismal triage of so-called Platinum, Gold and Lead titles, the latter being unwanted acquisitions given the most cursory treatment to satisfy contractual bundles – a single font, no marketing, and sometimes no editorial attention. No wonder nobody bought them. She details the immense ruptures caused by the rise of digital publishing, not merely in the prospect of paperless books, but in the avenues it created at every stage of the chain – speeding up contacts, outsourcing translation and off-shoring design (lettering is now done in Indian sweatshops at $1 a page), as well as crowd-sourcing projects, making the customers bear the entire brunt of the investment.

Some of us, of course, saw the slump coming from way off, as companies first tried to take out the damage caused by their bad decisions on their employees. During the manga boom she describes, the price of translation fell through the floor, causing many translators to quit the field. In my case, I gave up translating manga around 1998, when my choice was to accept McJob money or to produce shoddier work. So no, Dr Brienza, I did not leave the manga business because “UK citizens… cannot reasonably be expected to be fully fluent in the American vernacular.” I left it because none of the Americans begging me to work for them could offer me more than $18 a day, and I could get ten times the money translating a book by a guy who had been dead for more than two thousand years. So I laughed my socks off at her description of the end result of this, with linguists in such short supply at some of today’s companies that the staff have to trawl illegal scanlation sites for “research.” It’s hardly surprising, given the inconvenient expense of people who actually know about matters Japanese, that so many publishers would try to find a way to survive without them.

Brienza drives home the fact that an “American manga business” relates to the “American business” of manga, rather than the business of “American manga”, but nevertheless, the commissioning of original non-Japanese material still fits into her methodology. She points out that one of the impetuses behind the pseudomanga boom was the mealy-mouthed legal argument that a “manga” adaptation was somehow different from a “comic” adaptation, and hence often possible to renegotiate in a media contract that was otherwise inflexible. She also notes, very reasonably, that the American manga business was largely created, run and developed through the agency of Americans, and that many such figures arrived in a business that began as an enterprise to sell Japanese comics, and organically diversified into other concerns. And who can blame them? Her stories of certain resentful, obstructive licensors make it very clear why so many people in the American manga field might want to remove the “Japan” component from the things that they sold. In a rather touching note, she also observes that the presence of manga, and the belief, misguided or otherwise, that The Kids dug it and it was going gangbusters, was sufficient to significantly skew the kind of home-grown material that mainstream publishers were prepared to consider releasing.

“I would argue,” she writes, “that graphic novels like American Born Chinese and Amulet, by and for Americans, would not have been published by Marvel and DC under different conditions. They would, rather, have not existed at all.”

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History and has been writing the Manga Snapshot column in NEO magazine for the last ten years.

books, Casey Brienza, comics, Japan, Jonathan Clements, manga, Manga in America, pseudomanga

Leave a Reply