Books: Media Theory in Japan

March 8, 2017 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

Takashi Tsumura saw it coming. He suggested that the “computer line” and the television might one day be combined. Moreover, in a “somewhat radical hypothesis” that the Japanese broadcast and phone companies might also combine, he suggested the “net” such a merger produced would have all the power and invasive persuasion of wartime state propaganda. It might all sound like a statement of the obvious to you, but Tsumura said it in 1973, in a journal of Japanese broadcast theory. His comments are impressively prescient, seemingly even running a little ahead of the prevailing trends in science fiction, which usually gets to all the good ideas before academia. The anime historian might observe he wrote them when the industry was already setting up think-tanks to deal with the onrush of computer technology before it had even been invented. Marc Steinberg and Alexander Zahlten, in their just published collection Media Theory in Japan, would just like readers to notice that Japanese pundits have had some interesting things to say over the years.

Takashi Tsumura saw it coming. He suggested that the “computer line” and the television might one day be combined. Moreover, in a “somewhat radical hypothesis” that the Japanese broadcast and phone companies might also combine, he suggested the “net” such a merger produced would have all the power and invasive persuasion of wartime state propaganda. It might all sound like a statement of the obvious to you, but Tsumura said it in 1973, in a journal of Japanese broadcast theory. His comments are impressively prescient, seemingly even running a little ahead of the prevailing trends in science fiction, which usually gets to all the good ideas before academia. The anime historian might observe he wrote them when the industry was already setting up think-tanks to deal with the onrush of computer technology before it had even been invented. Marc Steinberg and Alexander Zahlten, in their just published collection Media Theory in Japan, would just like readers to notice that Japanese pundits have had some interesting things to say over the years.

A couple of months ago, I was sitting in on the viva voce – the oral examination that usually precedes the conferral of a doctorate – of a PhD candidate from China. His topic was a facet of global digital media, but his references were universally from the English-speaking world. I asked what had been written on the subject in Chinese, and he replied with a shrug that he was under no obligation to incorporate foreign language research in his findings. It was seemingly an attitude shared by his entire field, that if something didn’t happen in English, it didn’t happen at all. I thought he missed a real trick by failing to introduce ideas from his native language not only to his dissertation, but to his foreign colleagues. From my cursory glance at the literature in Mandarin, it was likely that Chinese research in this area was a decade behind the times, but even that might be a worthwhile fact to discuss, if only to dismiss. It was certainly worth knowing for sure before proclaiming oneself an expert.

It’s omissions like this that Steinberg and Zahlten hope to address. The chapters they curate in Media Theory in Japan point to numerous Japanese scholars whose ideas are not only unknown in the West, but seemingly unloved in Japan, where too many of their own colleagues cling to the shiny, exotic ideas of foreign theorists.

It’s omissions like this that Steinberg and Zahlten hope to address. The chapters they curate in Media Theory in Japan point to numerous Japanese scholars whose ideas are not only unknown in the West, but seemingly unloved in Japan, where too many of their own colleagues cling to the shiny, exotic ideas of foreign theorists.

As noted in their introduction, “Japanese models of industrial production were the subject of great interest – and much hand-wringing – from the 1980s onwards.” Western researchers were obsessed with robot factories and the Just-In-Time system, but nobody, it seems, cared all that much about the Japanese media, even as the Japanese media came to dominate several areas of transnational entertainment. Japan has one of the largest publishing industries in the world, containing local products that remain tantalisingly invisible to the non-linguist, as well as familiar Western books in translation, that are translated into Japanese with varying degrees of time lag. The critic Edward Fowler once suggested, only half in jest, that the best indicator of Japanese tastes would require not a translation of Haruki Murakami, but of Stephen King, out of Japanese and back into English. It would not necessarily be the Stephen King we think we know.

As Marc Steinberg points out in his chapter on Marshall McLuhan, such misunderstandings can themselves form a new and valid conversation, filtered through “local inflections” that in the case of McLuhan, saw him reinterpreted in Japan as a marketing guru and a prophet for the managerial class. There are, for Steinberg, several McLuhans – starting with the foggy local misconceptions about him before he was properly translated.

Some may be misunderstood; others just ignored. Marilyn Ivy writes an entertaining chapter on the rise and fall of InterCommunication, a Japanese media magazine that flourished during the “bubble-enabled cosmopolitanism” of the late twentieth century, and lumbered on through the first of the “lost decades” of economic stagnation, somehow managing to miss all the game-changing, iconic events of that period (the Kobe earthquake, the Aum Shinrikyo gas attack) in favour of navel-gazing art projects. Ivy finds the hardbound magazine archives occupying an entire shelf at Columbia University, where she proves to be the first person in a decade to check a volume out. This story turns her chapter into a meditation on the politics of reception – did anyone ever read InterCommunication? Should we regard it as a lone voice in the wilderness, a valuable archive for researchers of the future, or a pointless white elephant taking up library budgets and shelf space?

Some may be waiting for the right reader. Aaron Gerow introduces some new issues in his chapter on early theories of television, although he is able to call not only on his own previous publications on the subject, but also on Jayson Chun’s, so it’s hardly an unknown area in English. But one idea, buried away in his footnotes, is a captivating discussion of possible reasons for broad and predictable characterisation in TV dramas – not necessarily an example of bad writing, but as a form of storytelling that panders to the needs of a distracted audience. I’ve already made such an observation in my own writings on Japanese television, but as Gerow points out here, Hiroshi Minami made them long before me, in 1960.

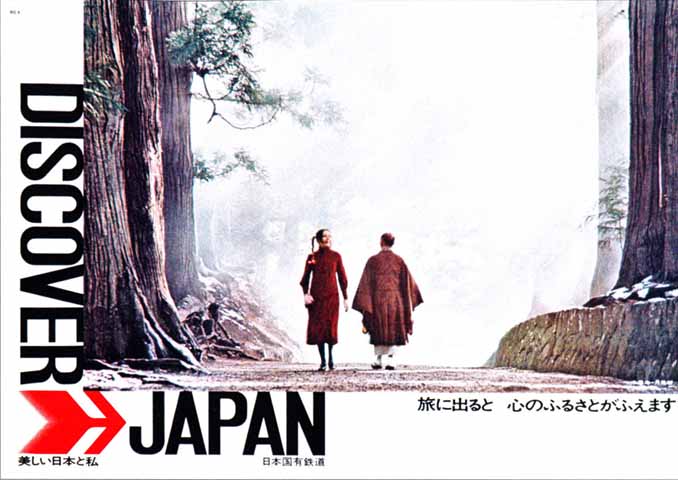

Tomiko Yoda presents an absorbing account of the way in which the Japanese mass media coped with a series of disruptions at the beginning of the 1970s to create a new, female-focussed area of consumption that would have repercussions for decades. Anticipating a drop in train usage following the closure of the 1970 Osaka Expo, the “financially beleaguered” Japan National Railways tore a leaf from the 1967 Discover America campaign, and devised an advertising strategy designed to push domestic tourism as the new cool, with nattily-dressed young ladies gorgeously photographed in all manner of castles, courtyards, temples and forests. These iconic Discover Japan images popped up around the same time as the Parco company ran its own campaign to push department stores concentrating on female fashion, presenting the first foreshadowings of a culture that would place the twenty-something yuppie girl with no rent to pay and a disposable income as the engine that drove the bubble economy.

Tomiko Yoda presents an absorbing account of the way in which the Japanese mass media coped with a series of disruptions at the beginning of the 1970s to create a new, female-focussed area of consumption that would have repercussions for decades. Anticipating a drop in train usage following the closure of the 1970 Osaka Expo, the “financially beleaguered” Japan National Railways tore a leaf from the 1967 Discover America campaign, and devised an advertising strategy designed to push domestic tourism as the new cool, with nattily-dressed young ladies gorgeously photographed in all manner of castles, courtyards, temples and forests. These iconic Discover Japan images popped up around the same time as the Parco company ran its own campaign to push department stores concentrating on female fashion, presenting the first foreshadowings of a culture that would place the twenty-something yuppie girl with no rent to pay and a disposable income as the engine that drove the bubble economy.

There is, of course, an element of chicken-and-egg here – were the advertisers creating a new niche, or were they reacting to realities in demographics? Regardless of what came first, the Hello or the Kitty, Steinberg and Zahlten themselves acknowledge that the history of Japanese media has all too often been left in the hands of a “very male clique”, spuffing enthusiastically about guns and boobs, while ignoring or marginalising the female audience. As noted in my own Anime: A History, this has become an issue in some areas of anime studies, where, for example, fanboy concentration on the “success” of Space Cruiser Yamato has largely swamped the equally popular, highly-regarded and ultimately influential TV run of Heidi, Girl of the Alps, which went toe-to-toe with Yamato in the ratings.

Hiroki Azuma’s theories of fandom get good coverage, but he is hardly ignored overseas – you can buy his Otaku: Database Animals in English. But Takeshi Kadobayashi’s chapter on Azuma does not so much revisit his otaku theories as place them within the context of his wider work, as one element of his ideas on post-modern media, blown out of all proportion by changes in circumstances and technologies. Much like Patrick Galbraith, who risked pigeonholing as “the Lolicon guy” because he dared to approach a hot-button topic, Azuma has been transformed into the poster-boy of Fan Studies weebs, to the detriment of wider-ranging elements of his thought. As Tom Looser notes in another essay on Azuma in the same volume, he has substantially more to say than that, not the least in his more recent writings post-Fukushima. I see Azuma cropping up in a lot of contemporary Japanese Studies dissertations, often from people who would be far better off using the more grounded, technologically derived periodisation of Nobuyuki Tsugata, who remains untranslated and sadly unmentioned in this book, despite his role in the assembly of the landmark collection Anime-gaku. But I digress – if you are citing Azuma in your schoolwork, you owe it to yourself to see what else he has to say.

Sometimes cultural theorists are their own worst enemies, so invested in coining clever new buzzwords that they forget to explain themselves. Both John Ellis, in Against Deconstruction, and the film studies polemics of Barry Salt have laid the blame for this confusion largely at the door of the French, who seem to possess an inexhaustible tolerance for letting old men witter and pontificate without due diligence. And if, like Ellis and Salt, you regard most media studies essays as a tepid puddle of self-regarding gobbledegook, I’m afraid that there are several parts of this book that will only confirm your suspicions. They are, however, greatly outweighed by the parts that are worth your attention.

One would think, in a book that championed access to foreign-language materials, that someone would have at least mentioned Toshie Takahashi’s Audience Studies: A Japanese Perspective, which has been available for eight years. Similarly, I wish there was a deeper treatment on “industrial strategies” – the Nomura Institute’s Otaku Marketing, for example or Tsugata’s aforementioned Anime-gaku. However, an appreciation of how the sausage is actually made and sold arguably takes us out of Media Studies into the applied world of actual Media, so such apparent omissions tell you more about my own interests than any significant flaws in the book.

That PhD candidate from China? I think he got a B. But if he’d thought more like Steinberg and Zahlten, he might have scraped an A.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History. Media Theory in Japan is published by Duke University Press.

Alexander Zahlten, books, Jonathan Clements, Marc Steinberg, media studies, Media Theory in Japan

Leave a Reply