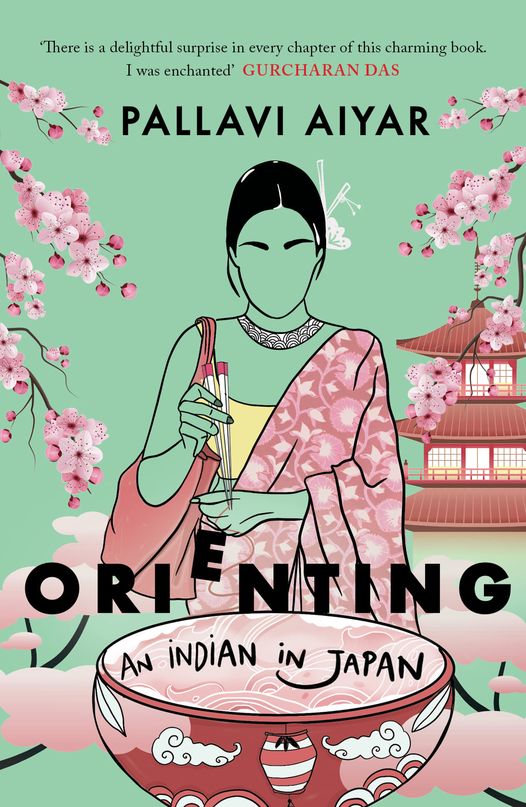

Books: Orienting

July 26, 2021 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

“My stay here has been so short,” said Rabindranath Tagore to Japanese students in 1916, “that one may think I have not earned my right to speak to you about anything concerning your country.” Pallavi Aiyar chooses to quote him in the final chapter of her Orienting: An Indian in Japan, a gentle apology for daring to add to the pile of books about the Land of the Rising Sun after only four years in the country. Her life around her in boxes, as she prepares to move to Europe mid-COVID in 2020, she frets about what her book is really about. “This book,” she writes, “was ultimately about me as observer, my circumstances and predilections, as it was about Japan.”

She says that like it’s a bad thing, like I wouldn’t want to hear her views on smart toilets and manhole covers, Tokyo’s “Little India” and the miseries of learning Japanese. All travel books are as much about the traveller as the place travelled. But equally, one’s travelling companion, in real life or in prose, can have a transformative effect on how you see the world.

The “by the same author” section at the front of her book foregrounds Aiyar’s more ephemeral populist work, including two books about her cats (which I am sure outsell everything else) and an earlier memoir on China. But it doesn’t mention Choked, her polemic about air pollution, or New Old World, in which she turned her outsider’s perspective on the inscrutable people of Europe. This, I suspect, is either the result of some publisher-specific demarcation, or an attempt to make her seem less experienced, less practised at observing the world around her, as if she is some student on a gap-year, blogging chattily for her friends, and not a cosmopolitan author who is currently an associate editor for The Globalist.

This is a disservice. Aiyar is a professional outsider, adept at dropping into an entirely alien culture, and ready to grab hold of it with both hands. She is not some listless plus-one, wearing out a groove between Starbucks and the diplomatic compound, she is an accomplished flaneur and enthusiastic student, flinging herself into cultural pursuits and research.

You have to pick your travel writers with care, lest you be stuck with some insufferable dude-bro or drama queen. As with her earlier work on China, Aiyar’s most obvious selling point is the perspective she offers from her home country, right from the moment when she observes that an old-time Japanese world for the world was “the Three Countries” – meaning the only places that mattered, China, Japan and India. Aiyar is fascinated by the transformation that Buddhism has undergone in China, as revealed by kintsugi (repairing broken ceramics with gold) and the tea ceremony.

She also grapples with what it means to be a parent in a foreign country. Oh, you carefree backpackers and travellers, showing up at the airport with just a pair of knickers and a toothbrush, waiting to see where travel and Tinder will take you. Try washing up in Shanghai at two in the morning and needing to find diapers, milk formula and a safe playground.

Aiyar already knows what other newcomers to Japan have said, and doesn’t waste your time with coffee in cans or underwear vending machines. Instead, she dives straight into what it’s like being a mother in Japan, fuming at the lack of bus provision at her kids’ expensive school, and then dropping her jaw in amazement at the reason: that’s it’s perfectly safe for a lone six-year-old to travel across Tokyo on public transport. You might think the ubiquitous convenience store is the place to buy tickets to the Ghibli Park and a pot noodle. But they are also the anchors of Japan’s children’s safety, boltholes for lost kids that offer free phone service to contact parents. A child wearing a yellow hat or patch on his or her uniform is a newbie to solo travel, subtly signalling to all around them that they might need a little guidance.

Having lived for several years in China, the subject of her first book, Smoke and Mirrors, Aiyar also comes loaded with an appreciation of things Chinese. I feel for her at a park full of cherry blossoms when she overhears some boorish pig farmer bellowing in Mandarin that he’s off to have a dump. Her arrival in Japan coincides with the grand expansion of Chinese tourists, which has been greeted by the Japanese with a succession of tuts, tsks and horror stories. But her grounding in China also brings with it a healthy cynicism for claims of Japanese essentialism – unlike many a weeb nodding enthusiastically about how peach blossoms, moon-gazing and poetry is all so uniquely Japanese, she can see just how much has been imported from elsewhere. She also can see immediately how the nihonjinron philosophy of Japanese uniqueness carries with it a certain nationalist, braggart taint, and quotes Tagore on pre-war Japan’s worrying tendency to “imbue the minds of a whole people with an abnormal vanity.”

She tracks down Yogendra Puranik, the first Indian to be elected to public office in Japan, which itself propels her into an investigation of Japanese attitudes towards all foreigners, including the Chinese, Indians, and Koreans (even “Koreans” whose families have lived in Japan for a century). She observes that Japan has twice selected dark-skinned women as beauty queens, including the half-Indian Priyanka Yoshikawa (pictured at the top of this article) and that “I certainly could not imagine a half-black Miss India, for all my home country’s surface plurality.” Her eye for fellow outsiders brings a revealing comment invisible to most first-time visitors: that immigrant labour is already vitally bolstering Japanese society: care homes staffed by Filipinas and convenience stores run by Vietnamese and Nepalese.

In the midst of the prime minister’s mad quest to get a UNESCO nod for Japanese cuisine, Aiyar chafes at a tourist junket menu that is all-kaiseki, all the time. In a refreshing side-turn from others enthusing about sushi and grilled fish, she confesses that she and her boys really love the pizza in Tokyo. Her true triumph, however, is her investigation of the history of curry in Japan, not merely in its adulterated heat-and-eat form, but in terms of the life of Rash Behari Bose, the Bengali rebel who fled the Raj to start Tokyo’s first ever Indian restaurant. Bose’s quest to bring real curry to Japan is presented not merely as a tale of restaurant grit, but of a devoted Indian trying to persuade the Japanese that what they think of as “curry” is actually a bastardised British knock-off.

Similarly, Aiyar presents an admiring account of the man who is probably the most famous non-Bollywood Indian in Japan, Judge Radhabinod Pal, the sole dissenting voice at the Tokyo war crimes trials, commemorated with a slightly misleading memorial at the Yasukuni Shrine. While it’s sweet for her to acknowledge that many, many other people have written books about Japan, exactly none of them have picked the exact same things, people and places to write about, and few of them have approached it with her heart and insight.

Orienting: An Indian in Japan is published by Harper Collins India. Jonathan Clements is the author of A Brief History of Japan.

Leave a Reply