Books: Totoro for Two

May 18, 2019 · 0 comments

By Motoko Tamamuro.

For months after the release of Laputa: Castle in the Sky (1986), Hirokatsu Kihara waits for news of the next production for Studio Ghibli. The studio suddenly gets lively when the announcement comes that the next film will be Grave of the Fireflies, directed by Isao Takahata. However, nobody says anything to Kihara. He feels left out, until suddenly Hayao Miyazaki pats him on the back and says: “Mr Kihara, we two will start Totoro.”

For months after the release of Laputa: Castle in the Sky (1986), Hirokatsu Kihara waits for news of the next production for Studio Ghibli. The studio suddenly gets lively when the announcement comes that the next film will be Grave of the Fireflies, directed by Isao Takahata. However, nobody says anything to Kihara. He feels left out, until suddenly Hayao Miyazaki pats him on the back and says: “Mr Kihara, we two will start Totoro.”

Totoro for Two: Hayao Miyazaki and the era of My Neighbour Totoro is Kihara’s second memoir of his career at Studio Ghibli, currently only available in Japanese. The first one, Another Balse: Hayao Miyazaki and the Era of Laputa: The Castle in the Sky, was published to commemorate the thirtieth anniversary of Laputa, and it was only a matter of time before a similar volume followed on My Neighbor Totoro (1988). If anything, this volume improves on Kihara’s insightful, interesting earlier account, possibly because Totoro itself remains dearer to his heart. Although the director is king in an anime production, the reader is left sometimes feeling as if Miyazaki and Kihara were more like a married couple or a comedy duo.

Miyazaki, claims Kihara, is so impressed by Kihara’s passion and dedication on Laputa that wants this young man to be on the Totoro production desk, responsible for the scheduling and budgeting of his new film. Kihara is over the moon, but initially declines the offer. He knows the limit of his abilities – he needs more experience. But Miyazaki is adamant, because he does not want someone who works for work’s sake. Kihara has no choice but to give in.

Miyazaki, claims Kihara, is so impressed by Kihara’s passion and dedication on Laputa that wants this young man to be on the Totoro production desk, responsible for the scheduling and budgeting of his new film. Kihara is over the moon, but initially declines the offer. He knows the limit of his abilities – he needs more experience. But Miyazaki is adamant, because he does not want someone who works for work’s sake. Kihara has no choice but to give in.

“Listen,” says Miyazaki, “I need to make something clear. This is a happy piece. Please produce it happily. That’s all I ask of the production desk.” A cynical reader might sense portents of Miyazaki’s infamous but world-beating refusal to pay attention to real-world fripperies like budgets and schedules – surely “happiness” should be a long way down the considerations of a production desk, the occupant of which is liable to have to deliver bad news and crack multiple whips? But Kihara reports Miyazaki’s intention to establish “happiness” as a baseline on the Totoro production, convinced that such an atmosphere would be reflected in the final product.

Kihara takes him at his word, recruiting a mainly female staff of experienced in-betweeners in the hope that more delicate line work and subtle depictions would bring Totoro to life. Grown-up women, he reasons, were once little girls like the characters of Satsuki and Mei, and could impart a certain naturalism to the film. Here, too, is a starry-eyed pronouncement with hidden implications – it’s a short step from Kihara’s typecasting of his animators to ethnically, racially or gender-delimited hiring policies. But Kihara’s account, boastful with 20/20 hindsight, reports a working environment suffused with joy, in which not a day passes without laughter, even at the most stressful times.

Kihara suggests that the heavily female staff causes the cantankerous Miyazaki to take things easier. If we are to believe his account, Miyazaki the notorious chain-smoker seemingly found less need to puff on his cigarettes in a less stressful environment, nor does he find the need to shout or display his irritation.

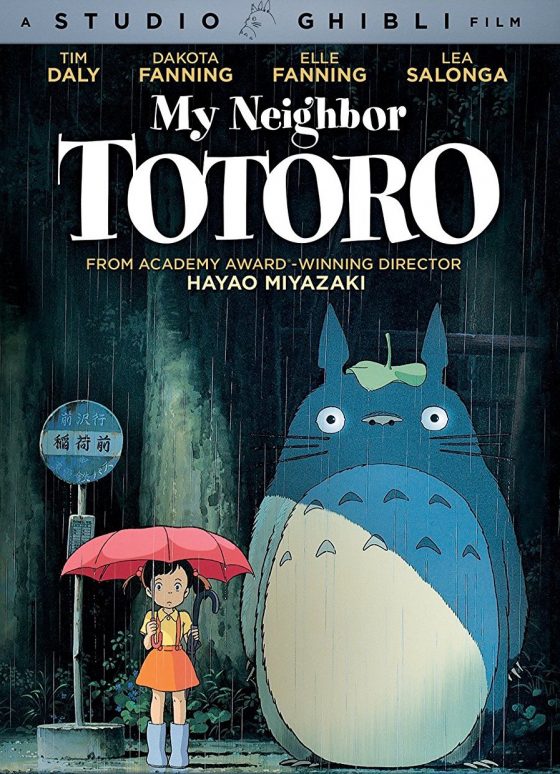

Then again, Kihara points to the possibility that Totoro itself was something of a dream project for Miyazaki, its first three storyboards drawn as early as 1975, soon after the completion of Heidi, Girl of the Alps. The iconic image, of Totoro and Mei standing at the bus stop, was already in embryonic form twelve years before production began on the film, as was the famous Catbus, both originally conceived as ideas for a picture book. In 1979, Miyazaki pitched Totoro as a TV special, without success – the film production is hence third-time lucky for him, an idea slowly warmed up over more than a decade. With his customary eye for incidental detail, Kihara points out that the Totoro storyboards contain remarkably few marginal doodles – Miyazaki is having too much fun drawing that he doesn’t stop to ponder.

Halfway through production, the team is showing signs of exhaustion, and Miyazaki decrees that they will have an outing in the countryside. In part, this is a team-building exercise, but also a side-effect of Miyazaki’s own working methods – he has refused to provide them with excess background material, and instead insists that they work for their own, personal observations of the natural world.

Halfway through production, the team is showing signs of exhaustion, and Miyazaki decrees that they will have an outing in the countryside. In part, this is a team-building exercise, but also a side-effect of Miyazaki’s own working methods – he has refused to provide them with excess background material, and instead insists that they work for their own, personal observations of the natural world.

Miyazaki becomes so involved with his heroines that the film’s final obstacle leaves him paralysed at his drawing board. As Satsuki searches for her missing sister, he looks up from the next blank page and asks Kihara: “Have I cornered her too much? It is too painful for me to continue.” His avowedly happy film faces a moment of jeopardy, and he is troubled by the injection of real drama into a story that is supposed to be all about joy. Should they abandon joy altogether?

Miyazaki’s hesitation convinces Kihara that he is creating a classic: that Satsuki’s moment of truth should be a reassertion of joy and faith, which Miyazaki eventually solves [spoiler warning, in case you haven’t watched Totoro at some point in the last thirty years] by having the Catbus bound to the rescue, Mei’s location literally listed as its next stop. “We have cornered the audience at this point,” says Miyazaki with a smile, “so it’s best that the children can rejoice now. We can see Mei, she is safe!”

Kihara finishes with a flash-forward to the present day, as he is putting the finishing touches to his memoir, and the Japanese media lights up with news stories about the death of Isao Takahata. He sees Miyazaki on television, delivering a tearful eulogy about the director known to all as Paku-san: “I’ll never forget Paku-san talking to me at that bus stop on that rainy day, fifty-five years ago.” With a flash of insight, Kihara realises why Miyazaki has always refused to update his original Totoro image board, refusing to draw the two girls. Even in the promotional posters for the film, he kept resolutely to his original picture, of a lone girl waiting with a Totoro spirit, even though that was no longer what happened onscreen. But Kihara realises the importance of the original image because of its deep personal meaning to Miyazaki: the rainy day long ago when his career truly took off, a lone human being falling under the spell of a benign deity. This closing revelation transforms the meaning of the entire book, and of the notional couple that it is about. When I finished reading, I had tears in my eyes.

Totoro for Two (Futari no Totoro) by Hirokatsu Kihara, is currently only available in Japanese.

books, Hayao Miyazaki, Hirokatsu Kihara, Isao Takahata, Motoko Tamamuro, My Neighbour Totoro, Studio Ghibli

Leave a Reply