Cyber City Oedo 808

December 3, 2020 · 7 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

With three hundred years to serve in consecutive life sentences, three hardened criminals in the 29th century are given an offer they can hardly refuse. If they are prepared to take on dangerous law enforcement cases, they can knock years off their sentences. But if they disobey orders or try to run, they will literally lose their heads.

Cyber City Oedo 808 (1990-91; UK 1994-95) focusses on just three of the crooks-turned-cop in the Cyber Police, the anti-social hard-nut Sengoku, the boxer-turned-hacker Gogol, and the androgynous master-thief Benten. From the opening shot, in which the camera pulls back from the view in Sengoku’s orbital prison cell, the production is marked out unmistakeably as a work by director Yoshiaki Kawajiri, much beloved by foreign audiences in the 1990s for his moodily lit, flashily shot works of urban gothic, and who would go on to make the fan-favourite Ninja Scroll.

Here, we are still in his sustained burst of creativity in the late 1980s that saw him taking a hands-on approach not merely to directing, but to the design of the characters in his films, in collaboration with his key animators. In the first moments of Cyber City Oedo 808, the screen is soaked in what critic Nobuyuki Tsugata has termed the “Kawajiri Blue,” a wash of pop-art azure, offset by the director’s other primary passion, a flash of red as the cell door opens. Buried among the key animators and layout artists are a slew of other names that would stick with Madhouse through the decade and beyond, including Hirotsugu Hamasaki, who would go on to work on Redline and Trigun: Badlands Rumble, and Michio Mihara, whose later projects included Spriggan and the films of Satoshi Kon. A young Takeshi Koike, who would go on to direct Redline, designed Cyber City’s various machines.

It’s never made all that clear why the Oedo police are so desperate for recruits that they have to drag convicts out of prison. As a military officer observes in episode two, there must surely be less risky ways of getting people to enforce the law, not the least because although the Cyber Police do face some dangerous situations, they are hardly the earth-shatteringly impossible missions implied by their last-ditch, suicide-squad task force. Maybe people in the 29th century have got better things to do than join the police, like… sit at home and read? Blink and you’ll miss it, but when he is prodded out of Cell #808 in prison, Gogol is reading a copy of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment… in Russian. In episode two, he is nose-deep in Malchiki (Boys), a story by Anton Chekhov.

In a touch straight out of period drama, the recruitment officer Juzo Hasegawa places a jitte in front of his three unwilling hirelings. It might look like something from a toolbox to foreign eyes, but in Japanese culture this humble dagger-like item was emblematic of an entire culture. The jitte was a parrying weapon, designed to stop a samurai’s sword. It was carried by Shogunal officials, forbidden from bearing arms within the Shogun’s palace, and in skilled hands could not only block a blow, but twist a sword clean out of an attacker’s hands. As something of a non-violent alternative to the swords on display all around Edo, it became a symbol of the city’s law enforcement – a man with a jitte, one could assume, was charged with keeping order, and might even be so bold as to stop a samurai from straying onto the wrong side of the law.

The Japanese urban gothic of the late 1980s could often seem like a traditionalist response to the cyberpunk movement. Whereas William Gibson began his Neuromancer (1984) with a view over a gritty, near-future Tokyo Bay – “the sky above the port was the colour of television, tuned to a dead channel” – many Japanese creators, particularly in the anime field, seemed to respond with a template born of cyberpunk + horror and legend.

Cyber City Oedo 808 was made in a critical moment in the history of Japanese animation. At the very height of Japan’s “Bubble” economic boom, which ran from 1986 to 1991, anime was attracting substantially higher investments than it had seen before. Confident in video success, and hopeful for foreign attention, the backers of Kawajiri’s earlier Wicked City (1987) had let him talk them into upgrading the project. What had once been intended as a work released straight-to-video was bulked up with enough footage to become a stand-alone movie. It would ultimately become one of the flagship titles of the UK’s anime boom, becoming one of Manga Entertainment’s top ten titles, but that long tail of overseas success was still in the future.

Since making Wicked City, Kawajiri and his stablemates at the Madhouse studio had lapsed cautiously back into lower-budget video, knocking out Demon City Shinjuku (1988), their second work based on the fiction of Hideyuki Kikuchi, and Goku: Midnight Eye (1989), based on Buichi Terasawa’s sci-fi respray of the legends of the Monkey King. They had also found themselves with a ringside seat as rival companies were garlanded with acclaim for high-budget SF projects – Gainax’s Wings of Honneamise carried off the Seiun Award in 1988, the same year that Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira would change the face of Japanese animation.

The appeal of the number 808 to Tokyoites is rooted in its samurai past. During 250 years of the Shoguns’ rule, their base at Edo-juku (Estuary Fort), eventually expanded into the sprawling city of Oedo (Great Edo). Packed out with outposts, servants’ and artisans’ quarters and multiple mansions for visiting delegations from the feudal domains, what was once a small castle town gained so many outposts that it swallowed up dozens of surrounding villages. Many of the names endure today as Tokyo districts – Shinjuku (the New Mansion), Nerima (the Tethered Horses), and Ibaraki (Thornbush Fort), to name but a few. The locals in the Shogun’s day would brag that Oedo was so large that it contained “808 districts.”

The number 808 had a double meaning in at the turn of the 1990s. It was also the quintessence of techno, the model number of the Roland TR-808 Rhythm Composer, the drum machine that launched a thousand house tracks. But it was chiefly a call-back to the samurai period – a lost era steeped in imagery from woodblock prints and kabuki. And there were plenty of studios ready to cash in on that cyber-samurai crossover – largely and perhaps justly forgotten today, 1988 saw the release of Toei Animation’s answer to the zeitgeist, Atsutoshi Umezawa’s Samurai Gold, which attempted to upgrade the tattooed kabuki crime-fighter Toyama no Kin-san with a light sabre, a blue-haired girlfriend, and a super-computer called EDO.

Cyber City Oedo 808 was conceived at the Madhouse studio as a similar mixture of science fiction, hard-boiled noir and jidaigeki (period drama – usually glossed in foreign criticism as “samurai” stories). However, it plainly owes a debt to the film that the Japanese call Special Assault Great Battle, better known in its homeland as The Dirty Dozen (1965). The idea of setting a bunch of condemned criminals on a mission to win back (at least partly) their freedom, and of setting it in a cyberpunk Tokyo, is credited here to one “Juzo Mutsuki”, a name which any Japanese reader can immediately tell is false, since it is simply a date: 13th June. It is, in fact, the date of birth of the man also known as Masayoshi Kubota, involved in several games and anime from Artmic, Enix and Madhouse, the founder of the Marcus software company, and later, with his wife Kei Arisugawa, one of the founders of Wonderfarm.

Mutsuki’s idea was pitched as a “media mix” – intended to hit the market as not only an anime, but also a computer game and a series of novels. It was conceived as an entirely in-house product, not packaged for an outside client like Wicked City, but entirely owned by the studio. Madhouse’s three-part video series would form only one facet of the franchise, which would ultimately also comprise a PC game and three novels by screenwriter Akinori Endo.

In Cyber City Oedo 808, the old Shogun’s city has now been turned into a somewhat unconvincing future acronym: O.E.D.O., the Oriental Electric Darwinism Oasis. The clash of old and new is signified in our first glimpse of Sengoku at work, as he waits in a chugging muscle-car beneath iconic cherry-trees shedding their blossoms, and then completes an incredibly unlikely stunt, leaping off a bridge and out of his car to apprehend a fleeing criminal in a hover-vehicle. It’s not a shot that one would expect to see in the realist science fiction that took over grown-up anime in the 1990s – it’s a ludicrous feat like something you would see in a bunraku puppet show.

That didn’t bother Mike Preece, the boss of Manga Entertainment during the wild three years that its videos clambered up the UK charts. In a notorious letter to the press and trade, Preece defined much of his company’s output as “beer-and-curry” movies, disposable fun for a drunken night and a good laugh. And much of the output he was describing was indeed from the Madhouse studio, animators on Wicked City, Demon City Shinjuku, and Lensman. Cyber City Oedo 808 was a perfect example, a trilogy that had come to a close in Japan in 1991, the very same year that Manga Entertainment’s Andy Frain got a plane to Tokyo to snap up anything that looked like it might do the same retail numbers as the phenomenal Akira. Cyber City Oedo 808 was a cartoon your granny wouldn’t like, with eye-popping violence, and more F-bombs on the soundtrack than your worst-ever report card. The visuals, too, were conspicuously cool – Cyber City Oedo 808 would become one of the titles that enjoyed a dual life, prized partly for its value as a film, and partly as imagery to be slapped elsewhere to promote Manga Entertainment as a brand. A decade after its heyday, in 2010, it was still striking enough to be plundered to make the eye-catching “Innocence” music video for the drum-and-bass act Nero.

“We hadn’t got a clue what everyone saw in the product because none of us understood it,” Preece confessed in a 2011 interview with The Raygun. “None of us were Otaku, none of us saw any great depth to it. We knew it was highly controversial and we knew how to collaborate with our customer base in order to maximise Manga’s potential. We were with it but just far enough removed so as not to become of it and I really believe that’s why it was successful, as up to then the genre had lent itself to those who become so fixated with the product that objectivity for its marketability is blinded by passion for content.”

A generation after Preece’s reign at Manga Entertainment, I watched a rowdy, drunken crowd at Scotland Loves Anime repeatedly losing its shit over a screening of Cyber City Oedo 808. The sweary dubbing, which even Preece himself once called “heinous,” was now the source of much hilarity, while the literally cartoonish stunts were greeted with good-natured jeers. He had not been wrong about the appeal of his product to a “beer-and-curry” crowd, even if its English-language presentation twisted it somewhat away from the played-straight techno-thriller of the Japanese original. The hard core of anime fandom in 1995 had disdained Manga Entertainment’s dub for outrageous liberties. At the film festival in 2018, they loved it for the same reason. The Japanese original, however, was not released in the UK; for audiences in the 1990s, the English interpretation was all there was.

The Japanese opening credits play under the rock song “Burning World: Memory’s Command”, sung by Hidemi Miura. This was stripped out for the UK’s Manga Entertainment release in the 1990s, and replaced with a new soundtrack by Rory McFarlane. This was not the only element of invasive localisation – in a sense, the last true grasp of the style in dubbing popularised by Carl Macek’s Streamline Pictures in the US, in which foreign release companies treated Japanese products as raw material, still awaiting fashioning into their final form, which would be whatever the company thought its customers would want. Today, it is assumed that those customers want faithful translation and respect for the original; in the early 1990s, Manga Entertainment’s dub sanded down some of the original’s exposition and scene-setting, in favour of wisecracks and subversion. When Sengoku takes down his first criminal, in Japanese, he observes that his black market data won’t do him much good in prison. In the English version, he tells him that “it’s far too late for a little lad like you to be out on his own.”

But this is all par for the course for Manga Entertainment mid-1990s dubs, in which the script adaptor John Wolskel, co-writer of I Bought a Vampire Motorcycle (1990), seemed to take a great deal of pleasure in “fifteening” up his jobs for the company, ratcheting the bad language, often for the cunning purpose of gaining a higher BBFC certificate and implying the material was more “adult” and edgy than it really was. You can also hear his work on fare like Psychic Wars, Mad Bull 34 and Violence Jack, which similarly come with American-accented voice actors, oddly slipping into occasional Anglicisms. And it’s him, presumably, we have to thank for little touches like Sengoku’s phone conversation to Okyo trapped in the elevator. In the Japanese version, he assures her that she will be back at her desk doing her paper-work the next day. In Wolskel’s English dub, he tells her that she’s lucky none of her fellow passengers have diarrhoea.

It should come as no surprise that the opening episode (variously known as Virtual Death, Time Bomb, or in the original Japanese, Memories of the Past) amounts to a sci-fi remake of Die Hard. The Bruce Willis vehicle was released in Japan in 1989, and was plainly a big hit with writer Akinori Endo, who had already tipped his hat to the movie that year with a novel about undersea mecha combat, Marine Battle Dy-Bard. Script work on Cyber City Oedo 808 came soon afterwards, with Endo returning to the idea of a fight over a skyscraper, also alluding to Die Hard’s distant inspiration, the disaster movie The Towering Inferno. But Endo’s storyline concentrates on an element that features in many more of his later novels and scripts – a mixture of a traditional ghost story with contemporary trappings. The tower that is holding 50,000 people prisoner is being “haunted” by the ghost of its own creator, a leading engineer thrown from a balcony by an embittered rival many years earlier. Now his spirit lives on in his computer code, a winning idea that had already been put to far more high-budget use in Kazunori Ito’s script for Patlabor: The Movie (1989).

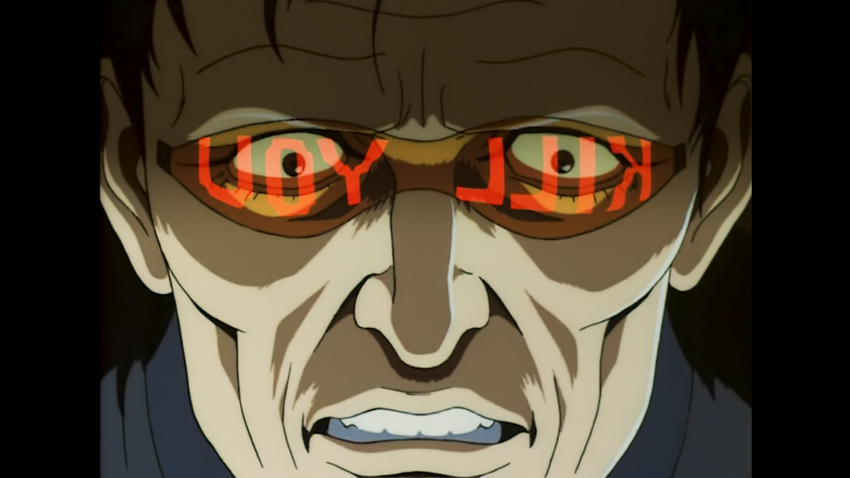

The opening of the second episode (The Psychic Trooper, or in Japanese, the Decoy Program) is palpably different in Japanese and UK versions, purely because of the sound. In the original Japanese release, we see Gogol climbing a ruined staircase in silence and shadow, the only noise coming from his footsteps and a few scattering birds. In the UK release, Gogol’s climb is accompanied by thundering rock guitars and drums from the McFarlane soundtrack. But the story is the same – a revelation, that Gogol, Benten and Sengoku are not the only special agents wearing exploding collars. Gogol has been sent to bring in Taku Yamahana, another man in the crew, but finds him tantalisingly close to unlocking his collar and running for freedom. But Taku’s new crime, which led to his fatal attempt at removing his collar, was the sale of Cyber Police data to an unknown client.

Whereas the first episode was at best a hostage situation or disaster movie, in which a crime was inadvertently solved amid the combat, the second episode puts the Cyber Police to work on actual detection. In a prescient consideration about the danger of data theft, Hasegawa wants to find who is prepared to pay such a high price for police files, but the investigation, such as it is, breaks out almost at random. In a story-telling mode that he would repeat on a broader scale in his later Cyber City novels, Akinori Endo’s script delivers three independent missions that accidentally hit on pieces of the same puzzle. Gogol’s exploding hacker has sold data to somebody; Sengoku finds the footprint of a military robot at a murder scene; and Benten halts a Chinatown operation smuggling dismembered body-parts.

As ever, what humour there is in the Japanese version was turned up to eleven by John Wolskel’s English script rewrite. In the Japanese original, Sengoku tells the nagging robot Varsus to get lost, only for the robot to explain that it has a global positioning system and is incapable of doing so. In the English dub, Valsus is left to contemplate the biological implications of being told to fuck off. When Sengoku finds Benten also sneaking around the army base, in Japanese he asks him if he is there to clean out the military sewers. In English, he asks him if he has “flushed an earring down the john.”

Gogol’s criminal connections allow him to guess that the hacker he is looking for is his former partner, Sarah. But she herself is working for the military, in a conspiracy that scales far out beyond simple data theft, into trade in human remains, and illegal cybernetics projects. As with the resonances of Patlabor in episode one, data theft is merely the gateway to a vast and corrupt crime that dwarfs the law enforcers in its size, and forces them to take on the establishment itself.

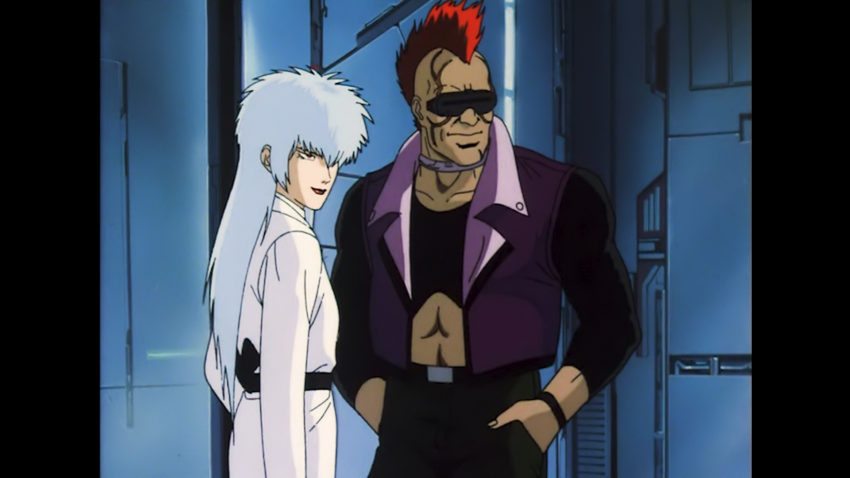

But it’s the third episode, (Blood Lust, or in Japan, Crimson Media) that remains the biggest fan favourite, not the least for its concentration on Benten, the androgynous, astrology-obsessed dandy with a mullet that should be a crime all of its own. He derives his codename from “Benten the Thief”, a notorious cross-dressing criminal in 18th century Japan, who was celebrated in several plays, beginning with Aotozoshi Hana no Nishiki-e (1863), in which at one point he infiltrates a bridal shop disguised as a woman shopping for gowns. In an era that was still resolutely “beer-and-curry”, the ambiguous and elegant Benten was a hit with the relatively small but growing community of female fans, becoming a recurring subject in the British Cyber Age fanzine that flourished in the late 1990s. His episode is conspicuously more stylish, leaning more heavily on Kawajiri’s urban gothic for a story that pushes hard to be a sci-fi retelling of vampire lore. Even in the English version, McFarlane’s rock soundtrack recognises the change in tone, held back in a more moody and spooky series of instrumentals.

Our sci-fi crime point of entry here is the murder of three geneticists. Our touchstone in Western media is Blade Runner, most notably in a scene in a Chinese bio-engineering chop-shop that references the lab of Hannibal Chew. Like Gogol in the previous episode, Benten tussles with a female associate who may have been a former lover, but his real quarry is Remi, the girl who has been awoken from centuries of slumber, hoping to find a cure for the disease that would have killed her in the less technologically aware past.

Interviewed in 2008 for a Plus Madhouse collection in his honour, director Yoshiaki Kawajiri ruefully commented that “there were still other stories to tell about Juzo Hasegawa” [the boss of the Cyber Police, apparently regarded by Kawajiri as the story’s true hero], and that further production was curtailed due to disappointing sales of the videos. There were other stories, of course, although they were never filmed. The CD-ROM adventure game Alignment of the Beast, in which Sengoku has to track down his companions and free them from captivity in order to defeat a greater boss, was released in Japan in 1991.

Depending on the degree to which we trust the claims that Cyber City Oedo 808 was intended from the outset as a media mix, Akinori Endo’s three untranslated 1991 novels were either always intended as spin-offs, or represent the scripts for three episodes that were never made. As with the original three video episodes, each of the novels concentrates on one of Hasegawa’s enforcers, but in a clever, post-modern touch, the stories take place simultaneously, each investigation crossing over with the other two, until the entire over-arching story is revealed by assembling the pieces. The first, Beowulf of the Rebellion, features Sengoku squaring off against a female bounty hunter in the slums of the city’s lower levels. The second, Lucifer Effulgent, pits Benten against a psychic assassin. The final part, Demon-Eyed Hercules, places Gogol centre-stage, as he follows the money-trail of HD=M55, a new drug with deadly side-effects.

Years after writing Cyber City Oedo 808, Akinori Endo would drift into retellings of classical Japanese ghost stories. We might regard his work on this anime as a forerunner of his later concerns, particularly in the way that each episode skirts around the issue of some form of life after death. Computers, cybernetics, or a virus – each episode offers its guest stars some semblance of immortality… but always at a price. The third episode, with its emphasis on psi powers and its visual evocation of horror movies, comes closest to Endo’s later interest in the supernatural. But in terms of unexpected “infections” conferring immortality, perhaps it also best mirrors the long-term appeal of Cyber City Oedo 808 itself, which is now remembered and celebrated far more for its UK versioning than for the Japanese original that has previously been unavailable to British fans.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History. Cyber City Oedo 808 is released on UK Blu-ray by Anime Limited.

Jon D

December 3, 2020 9:21 am

Why don’t Anime Limited try getting the rights to the Japanese CYBER CITY OEDO novels, translate them into English, and publish them as a trilogy novel collection? I know that UK CYBER CITY OEDO fans would really love these in their collections. I know I would.

Stephan

December 3, 2020 11:22 am

Yes! Been waiting for this one for a very long time! I agree with Jon D, it would be fantastic for the novels to be translated into English. Jonathan, is the above commentary of Cyber City Oedo 808 taken from your book?

Jonathan Clements

December 3, 2020 11:56 am

No, but it *is* taken from the 50-page "booklet" that Anime Limited are including in the Blu-ray release, which also includes interviews with Rory McFarlane and John Wolskel.

Stephan

December 3, 2020 12:02 pm

Thanks, Jonathan. Looking forward to reading those interviews too.

Rob

December 3, 2020 2:10 pm

Oh my Jonathan, thank you so much for this write up! What a trip down memory lane! This is the first news I've seen re this new release and it has quite literally made my day! For years, roughly 21 if memory serves, I have been dreaming of this... well more specifically by "this" I mean a definitive edition of one of my childhood (if 17 years of age can be considered as such) favourites! My well worn, though still very shiny Manga Ent UK VHS tapes along with their Cyberpunk Collection counterpart and even late night Channel 4 TV recordings from 1994/95 (anyone remember those?) still sit proudly on my bookshelf even if the tech I need to play them has long since ceased to work. This marked my first experience where the original Japanese version of a show I loved was completely underwhelming... from the score to the acting, everything felt very wrong about the experience, not helped at all by the abhorrently poor DVD mastering from US Manga Corps. I have passed on every subsequent DVD release of this classic since, though found myself randomly searching for info every now and then in the hope I would stumble upon a release including the UK Soundtrack... it certainly took a while, but boy does it seem like it was worth the wait!! Now, if Anime Ltd could kindly do the same for the Patlabor 1 & 2 movies with their respective Manga UK Dubs, and maybe find it in their hearts to give us a much tarted up release of Gunbuster with the original Chariots of Fire esque audio for Ep 1's titular training montage... well, let me just hand you the keys to my PayPal Account in advance :-) Thanks again for the great post!

Iain

January 23, 2021 1:26 pm

QC team miss out the cards/sticker sheet on this one?

karlos74k

August 26, 2022 2:19 pm

How can us fans get a hold (physically/pdf, etc.) of the fanzine?