Future Boy Conan & the Ratings

March 29, 2022 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

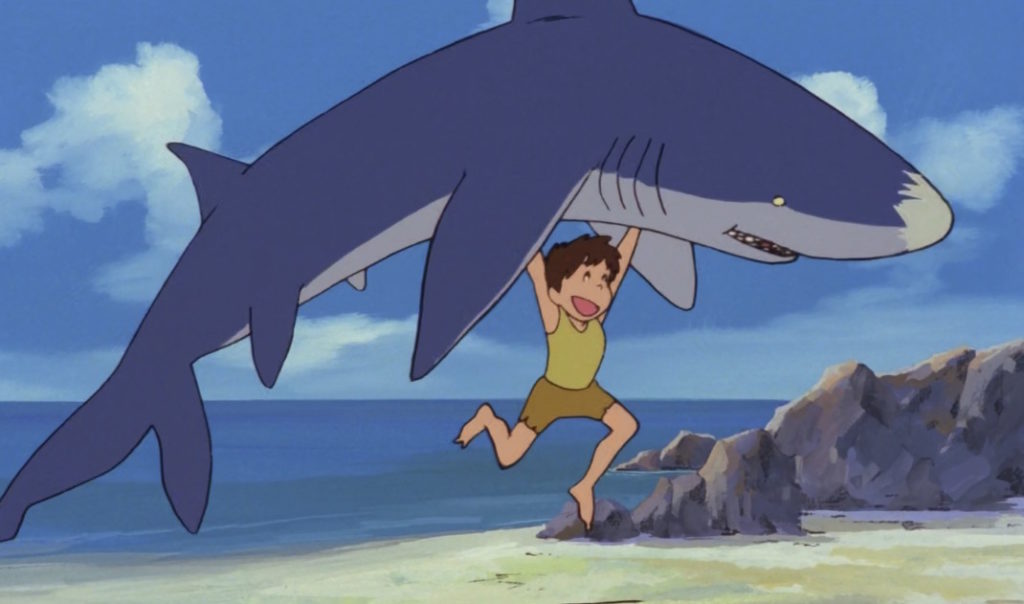

In a tongue-in-cheek reminiscence, Yasuhiko Tan, the NHK producer who greenlit Future Boy Conan over dozens of other possible projects, wrote of his interest in the show as if it were a deluded romance. Bewitched by the charms of the original offer, and over-awed by the appearance of the pilot episode, he alluded to the progress of his “relationship” as he continued to throw support behind a project that fell behind and became too big to fail, only to snatch disappointing ratings on broadcast.

“These days,” he wrote to Conan as if it were a fondly remembered ex, “people talk about you like you are the great anime masterpiece, but back then, your reputation, to be honest, wasn’t so good. The audience share didn’t meet up with people’s expectations, and I heard all sorts of stories. You know how difficult it is to hear bad things about the one you love, don’t you?”

In the 21st century, most anime producers would be more than happy with the sort of television ratings that Conan managed to achieve, but for its backers in 1978 it was a disappointment. In the days of only five major channels on air, an average distribution of viewers might allocate 20% to each – the sort of ratings one might achieve by randomly channel surfing. It was already understood that an audience share for a children’s cartoon of 15% would be enough to account for every child in Japan. This, then, would ultimately become the golden target, on the understanding that children were the primary viewership not only for the cartoons, but for the advertising messages contained within the cartoon breaks – sales of children’s anime-related merchandise rarely increased beyond the 15% audience share threshold.

However, expectations in the 1970s were higher, partly because of Miyazaki and his colleagues, whose work on Heidi in 1974 had been so well received that it achieved double the expected ratings in its time-slot, even while going head-to-head in the schedules with another much-loved anime, Space Cruiser Yamato. Even without advertisers to impress, NHK was expecting to see a return on their investment of audience shares in the 20s, but instead saw disappointing figures of a mere 8% for episode #1. Throughout its initial run, Conan struggled to climb out of single figures, and ironically even seemed to be more loved when it wasn’t on air – the biggest bump in audience share, from 7.6% to 12.8%, came after a two-week gap when it wasn’t broadcast at all!

But ratings are not numbers in a vacuum. They, too, come attached to a historical context. In the case of Conan, it ran at a 19:30 time-slot on Tuesdays in direct competition not only with the popular gameshow That’s a Perfect Answer [Pittashi Cancan], but also with another anime, Angie Girl on TV Asahi, which ironically was also partly made by Nippon Animation. Angie Girl leeched a number of viewers who might have otherwise been expected to tune in. Some viewers complained that Conan was not highbrow enough for a public broadcaster, although many of these comments seem to have come from disgruntled fans of the programme that had been taken off-air to make way for Conan. The live-action news show From Our Special Correspondent [Tokuha-in Hōkoku] had been running since 1964. “How disgraceful,” read one irate letter, “that the world-famous NHK is screening a television cartoon just as if it were a commercial channel, and cancelling a news programme on its behalf!”

Shoji Sato, who wrote Conan’s original story pitch, related an apocryphal story told to him by an NHK executive, about one complaint from an angry parent who felt he had lost the moral high ground: “This dad sees his child watching Conan and shouts at him: ‘Don’t watch those cartoons. Watch NHK!’ And the kid says: ‘Father, this is NHK.’”

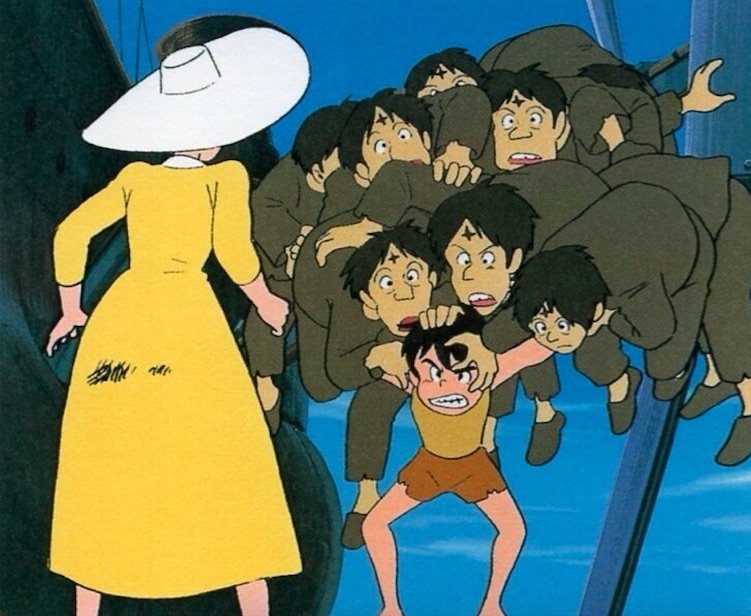

“I can sort of understand why the ratings weren’t so good,” Miyazaki confessed. “We were creating something that went against the grain of the times. Of course, some people later said that the ratings would have been a bit better if we had shown more of the Giganto plane flying earlier in the story.” The flight of the Giganto was a certifiable high point in the series, grabbing its largest audience share of 14.4%, and becoming a matter of some discussion among fans. As noted by Conan’s voice-actress, Noriko Ohara, the fans in question were not so much children as they were teenagers – the seed bed of the next decade’s otaku phenomenon, who commenced a letter-writing campaign that flooded NHK with almost 40,000 mails.

“More than anything else,” she wrote, “the parties concerned were all frustrated that such a good quality anime had been so misunderstood. However, just as the broadcast of all 26 episodes was over, everyone started talking about Conan, and the demand started to rise from people who had missed the show the first time around, or wanted to see it again. ‘Oh, they finally get it. We knew they would love it.’”

This is an extract from the book Future Boy Conan: Miyazaki’s Directorial Debut by Jonathan Clements and Andrew Osmond, which is included with the second part of Anime Limited’s Future Boy Conan collector’s edition. Part one is ready to order now.

Leave a Reply