Inu-Oh

June 11, 2023 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

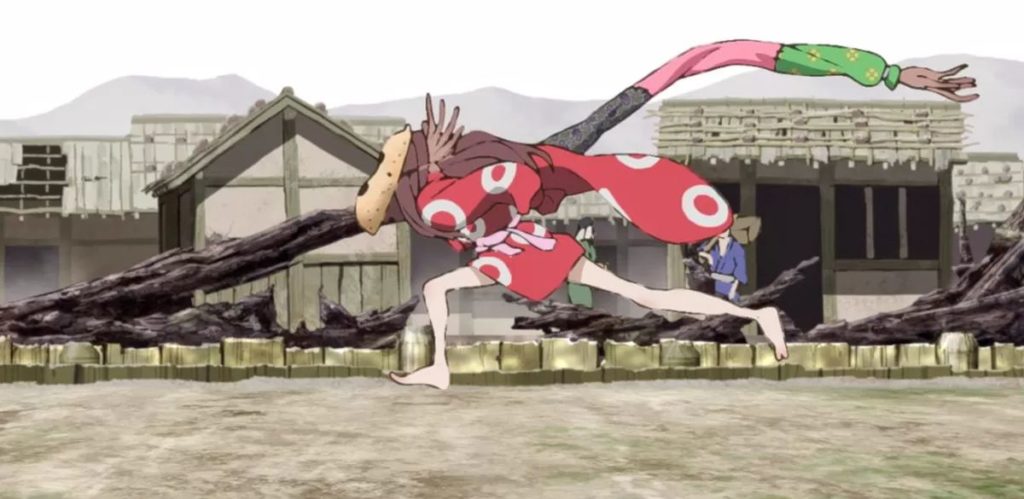

They meet one evening on a bridge in Kyoto, like those two samurai heroes of old, Yoshitsune and Benkei, but it has been 200 years since those legendary figures fought in the war commemorated in the Tale of the Heike. Now, in the 14th century, Kyoto is a gutted, ramshackle ruin, worn down by decades of samurai conflict, held in the unsteady grip of the Ashikaga shoguns. And these two youths are nobody of importance – Tomona (Mirai Moriyama) is a blind minstrel in training; Inu-oh (Avu-chan) is a disfigured outcast, the child of a family of theatre performers. And they are about to become rock stars.

Masaaki Yuasa’s Inu-Oh depicts two nobodies caught up in a scheme way, way over their heads, two characters literally sifting through the wreckage of a war that ended many generations in the past, but with scars that have yet to heal. Much as Akira’s biker-boys were drawn into a government conspiracy, Tomona becomes the collateral damage of a secret project designed to win the Ashikaga shogun the upper hand in an off-screen conflict. Japan has been plunged into its era of “Southern and Northern Courts”, rival regimes each claiming to back the true emperor. And some bright spark has come up with the idea that the way for the Ashikaga clan’s candidate to win, is to become the possessor of the three sacred imperial treasures, the Mirror, Sword and Jewel carried by the emperors since ancient times.

One small problem: Kusanagi, the sacred sword, was lost at sea in 1185, cast beneath the waves by the last of the Heike clan at the Battle of Dan-no-ura, where the Heike met their end against their Genji rivals. The bitter stand-off between the two houses, one with red banners and the other with white, has become an iconic division of the country not unlike Britain’s Wars of the Roses. To this day, it is echoed in the red and white teams of Japan’s annual New Year music contest, and even in the flag of Japan itself. But don’t take my word for it, here’s Carl Sagan explaining the whole thing with his customary brilliance, well worth eight minutes of your time.

The medieval Tale of the Heike had this to say about the aftermath of the battle: “The surface of the sea was thick with scarlet banners and scarlet pennants cast away, like scattered red leaves after an autumn storm on the Tatsuta River. The once-white waves that crashed upon the shore were dyed crimson. Masterless, abandoned ships drifted on the wind and tide, melancholy and directionless.”

But as director Yuasa notes, the war was not merely a time of catastrophic conflict, but a spur to artistic creation, as travelling bards began recording martial deeds in song, in saga-like chronicles like the aforementioned Tale of the Heike. It was, Inu-Oh suggests, a crisis that helped form the Matter of Japan, a terrible national event that only healed over the centuries as later generations processed the trauma at first as a form of exorcism, and later through the creative arts.

The depiction of Dan-no-ura in his film begins with a bird’s-eye view like wargaming table-top or a modern-day real-time strategy engine, before darting with creative mastery below the waves, to the battle as ‘witnessed’ by the largely uncaring fish on the sea bed. Suddenly, we are two hundred years later, and the fisherman’s son Tomona is diving amid the decayed wreckage, in search of relics of a lost age. Tomona’s family make a little money on the side by plundering the sea-bed, but now shady men have arrived from Kyoto, offering strings of coins to the first diver who can pull a particular item from waves. A sword, in a box, at a point marked on a map.

Actually, two small problems: the sword is cursed. Retrieved from the waters, it blinds Tomona and kills his father.

Blindness is a thorny thing to relate in a visual medium. Keiichi Hara’s Miss Hokusai also emphasised the “sound picture” of samurai-era Japan. Yuasa tries something a little different, creating impressionistic visions onscreen of how the sounds appear to Tomona’s mind’s eye.

“I wanted to portray Kyoto in the dark,” says Yuasa. “With very few street lights, it was pitch black at night. But in the darkness, Tomona sees the sounds he hears. At first, we see what he hears, but then we see images of the sounds that most capture his attention. Characters appear in the darkness, and filters are used on the drawings to create ambivalence.”

In one sequence, we are presented only with the most basic elements of Tomona’s sound picture – the slow-clopping of horse’s hooves, and the rustle of a package on its saddle. Because we “see” what Tomona hears, the package is immediately rendered transparent, because the noise Tomona hears is not the package itself, but the shaking of the rice inside it. And when the next sound is excited chirping, the imagery on screen tells us what Tomona has already realised… that the package is leaking rice, and local birds are pecking at a free meal behind the horse.

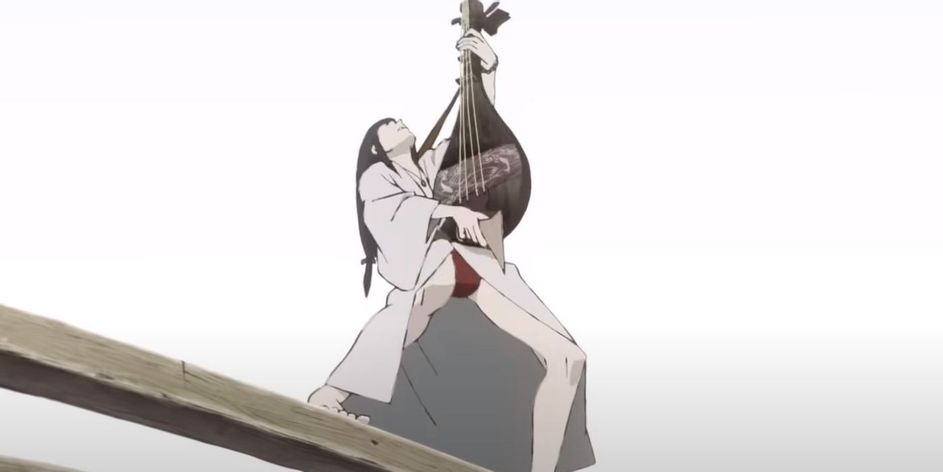

The film happily takes its time with such reveries, partly as an excuse to showcase everyday life of 14th-century Japan, but also to stretch out a life story in which, all too easily, nothing might have happened. There are moments where we see Tomona’s story might easily fade into obscurity, such as a scene where he is conferred with a new name Tomoichi, to reflect his apprenticeship to the biwa-player Hasuichi (Chikara Honda), one of the few professions available to the blind in old Japan. The news is supposed to be a great honour, but Tomona is literally haunted by the image of his aghast father, reminding him that he already has a name, and a mission to avenge him.

But Yuasa also works upon the viewer’s other senses, particularly in a scene in which Tomona and his mentor have an entirely mundane dinner in a dilapidated tavern. The focus of the dialogue, and the senses, is on the smell of Kyoto, the fact that the characters’ nostrils perceive a constant background whiff of fires and ash, indicating the ever-present series of street-fights and arsons that characterise the Ashikaga shogunate’s unsteady grasp on power.

Repeatedly Yuasa flits between ways of telling a story, creating a whirl of contesting narrative techniques evocative of Masayuki Miyaji’s Fuse: Memoirs of the Hunter Girl. The one that interests him the most is the bardic storytelling that first found prominence in the middle ages, a sort of song-talk that mixes dramatised narrative with spurts of song and musical stings. Not unlike similar sequences in Mizuho Nishikubo’s Musashi: The Dream of the Last Samurai, Yuasa drags the viewer into the middle of one such story, shilling with infectious enthusiasm for a lost art, augmenting the singer’s story with anime imagery, but evoking a world where the singer was all there was.

The casting for Inu-Oh hides some heavy-hitters up its sleeves. Mirai Moriyama, who plays Tomona is a stage performer in his own right, having played the lead in the Japanese production of Rent in 2008. He is also a familiar face on both the big and small screen. But the real coup comes in the casting of Inu-Oh, who is played by Avu Barazono, a.k.a. “Avu-chan”, the mixed-race, gender-bending lead singer of the pop group Queen Bee. Barazono had already made an impact in the anime world as the singer of the ending theme to Tokyo Ghoul: re, “Half” a song inspired on their own liminal identity between worlds. In particular, Barazono is known for a very wide vocal range, which they push to the limit in the performances of Inu-Oh.

The actors playing the two fathers who shape their children in very different ways are also of note. Tomona’s father, who dies in the film’s opening reel but lurks in ghostly form throughout (a very Noh thing), is played by Yutaka Morishige, best known to anime fans as Hokusai from Miss Hokusai. Inu-oh’s gruff father, obsessed with the “ultimate beauty” and tormented by his son’s disability, is played by Kenjiro Tsuda, an actor with a huge resumé in anime voice acting that includes Sadaharu Inui in Prince of Tennis, as well as Tatsu in The Way of the Househusband.

The crew is a collection of celebrated talents, including director Yuasa himself but also the acclaimed manga artist Taiyo Matsumoto (Ping Pong, Tekkonkinkreet) as character designer, and the award-winning screenwriter, Akiko Nogi (Library Wars, Fake News), adapting the original novel. But in a film that turns into a rock concert for a large part of its running time, it’s the music that matters, and for that Yuasa drafts in the composer and multi-instrumentalist Yoshihide Otomo. A former founding member of the band Ground-Zero, Otomo has composed scores for dozens of TV shows and films, including Tian Zhuangzhuang’s The Blue Kite and Anne Hui’s Summer Snow. He is deeply involved in Ensembles Asia, a society that seeks to establish musical links between different countries, as well as Sound Play Group, a music project for the disabled.

And then, of course, there is the director Masaaki Yuasa, who has already helmed one previous love-song to Kyoto in his acclaimed The Night is Short, Walk on Girl. Here, again, he thrills at the idea of Kyoto as a city out of time, where the ghosts of the past stare, baffled, at motor cars, while modern businessmen shuffle past the sites of ancient exorcisms and executions. We are propelled back in time from scenery of contemporary Kyoto, a thousand years back to the Middle Ages in a series of jump-cuts, stripping away the roads and buildings, until the great imperial capital of Japan is little more than a bunch of huts. But Yuasa has brought us here for a reason, the chance to tell a very tall tale about the moment in Japanese history where singing and talking to a crowd suddenly leapt up to a new level – when it turned into a primitive form of theatre. In telling a story about the transformation of Noh drama, so new-fangled here that word Noh is not actually use, and it is instead referred to as sarugaku, Yuasa is offering an origin story for the timeline of all Japanese drama, with the film we are watching as its most recent iteration.

“We often thing of history as moving in a single straight line,” explains Yuasa, “but it actually branches off, and the people in those branches have disappeared or been forgotten.”

The historical Inu-Oh (who died in 1413), exists as little more than a name and a few asides in ancient chronicles. In his day, he was a theatrical performer, highly regarded by the Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, to the extent that he was the superstar of his era, with a popularity greatly eclipsing that of his contemporary Zeami. But that’s part of Yuasa’s point – Zeami is remembered today as the “Shakespeare of Japan”, who with his father established many of the tropes and traditions that live on in modern Noh and Kabuki theatre. But in the 14th century, Zeami was a lower-ranking performer in Inu-Oh’s shadow, admiring of his elegance and delicacy onstage. Today, not a single one of Inu-Oh’s works survives, leaving his historical footprint shrouded in mystery. We don’t know anything about him, except that he changed everything.

Inu-Oh’s disability, it turns out, is the result of a curse – he has spent his whole life surrounded by the chattering, troubled spirits of fallen Heike samurai, the very same people whose war-graves the young Tomona plundered. But once the existence of this haunting is discovered, with the help of the cantankerous ghost of Tomona’s father, Inu-Oh starts to listen to their stories. And when he retells them, he does so with an immediacy that the other Noh performers have forgotten, new concepts in stage-craft and audience participation, with each ovation chipping away at a little more of his afflictions: drama as a healing process.

Noh, today, is notoriously staid and hidebound, an ossified performance technique trapped by the very traditions it is obliged to preserve. Every now and then, someone will find something to love about it – most memorably Ryosuke Takahashi’s Gasaraki, which used the power of Noh performance as some kind of fuel for giant robots (no, really). And animation, or at least motion capture, has become part of Noh’s modern-day existence, with an ongoing effort to digitise as many old masters’ performances before they are lost to posterity. But Yuasa wants to tear away all those assumptions, like he banishes the buildings of modern Kyoto, to show just how dynamic and exciting such drama must have been when it was new. He does it by throwing in an escalating number of anachronisms, emphasising the shock and awe of Inu-Oh’s and Tomona’s garish “new stories” and “new performances” by turning them into actual rock concerts.

“The biwa performances were born out of the desire to honour the fallen in battle,” says Yuasa. “The lost soldiers were mourned in Noh drama, and in songs by biwa priests. So, there might have been superstar performers even in that era. To us in the modern era, Noh is imposingly high-brow, but back then it, like Kabuki, was a popular entertainment. Modern Noh is slow-paced, but back then it was much faster. It was entertainment for the general public.”

Inu-Oh’s first concert is “under the bridge at Rokujo” but there isn’t a bridge at Rokujo, Kyoto’s “Sixth Street” – it’s another of the film’s historical teases. You can’t even walk from Rokujo all the way to the Kamo River today, without chain-sawing a tunnel through the Kyoto Community Centre (do not try this). There’s a bridge at Gojo (“Fifth Street”) of course, which is where Benkei and Yoshitsune had their famous showdown. And there’s one at Shichijo (“Seventh Street”), but Rokujo was known for something else in the time of the samurai, as being the site of the execution ground where the heads of dead Heike samurai were put on display. It is hence a spookily fitting place for Inu-Oh to suddenly launch into rock songs about cursed samurai, and lurid, visceral tales of the Heike clan’s desperate retreat.

As with Hideo Furukawa’s punk-style novel, from which the film was adapted, Yuasa deliberately introduces such anachronisms of technology and attitude, with the catch-all excuse that nobody can say for sure what didn’t happen. Yuasa relates his idea in science-fictional terms, bringing up a recurring element of Japanese Forteana – “out-of-place artifacts” or OOPArts.

“OOPArts are things that couldn’t exist when they did,” he explains. “Technologies that were too advanced for the times. Things that seem too advanced at that point in history. There were people who mattered, and events that were forgotten. And so, what if six hundred years ago there was a pop culture and celebrity like we have in Japan today? I thought there would be a real value in trying to portray the lost pop stars who aren’t mentioned in history.”

“People might not feel acknowledged by society,” says Yuasa, “even though they are strong and talented. I think there are people like that. But one’s talents will be noticed by someone somewhere. They’ll be passed on and remembered.”

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History. He hasn’t been to Kyoto since he was caught trying to chain-saw a tunnel through the community centre in search of a bridge that wasn’t there. Inu-Oh is released in the UK by Anime Limited.

Leave a Reply