Kaiba

December 5, 2021 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

The paradox of Masaaki Yuasa’s series Kaiba is that for much of the time, it’s a sad story, and yet there’s something joyous about it. What lies behind that joy would be expressed succinctly in a more recent Yuasa anime. At the start of his 2020 series Keep Your Hands of Eizouken!, a young girl investigates her new home, an apartment block. She explores everywhere; then she creates simple drawings in her exercise book, which we see animated into a world of pencil lines. They twist and turn as the girl, a crude drawing herself, runs happily around the wobbly stairs and landings, providing her own sound effects. Of course, she’ll become an animator, in the spirit of Yuasa himself.

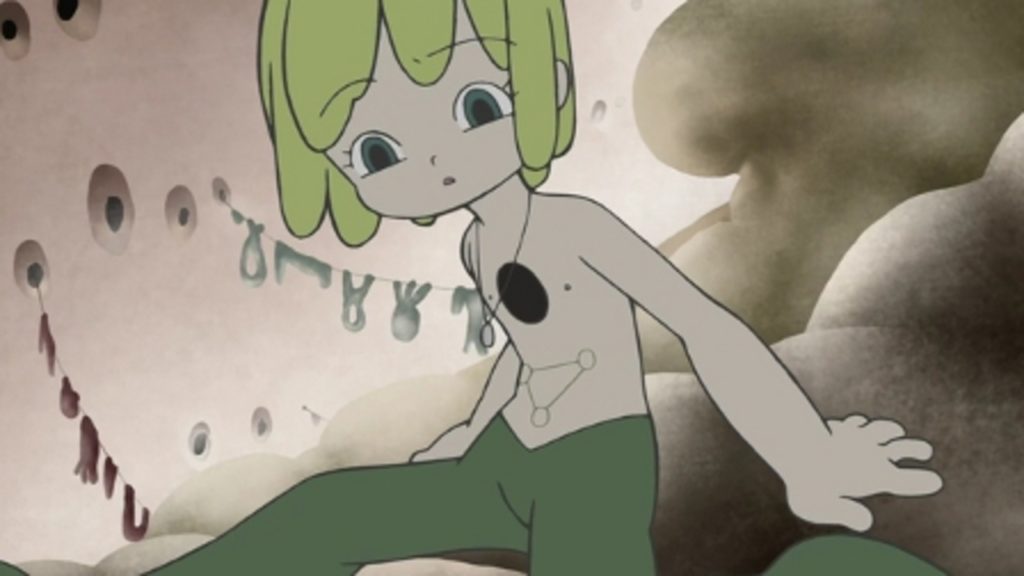

Made twelve years before Eizouken!, Kaiba is infused with the same spirit. At the start of episode 1, a cute boy with blond hair, and green leggings wakes on the ledge of a glassless stone “window,” overlooking a dilapidated town. Everything is rough-curved; perspectives feel crooked and interesting, like an adventure playground. A few scant moments later, the boy is being shot at, and out the window he goes, hurtled round walls, through tunnels and even into a rotating millwheel of sludge. The sequence clearly makes use of computer technology, and yet it feels like an immersive world of imperfect drawings.

“I want to see more relaxed animation coming from Japan,” Yuasa told the Screen Anarchy website in 2013. “Animation where everything is not so perfectly drawn. The strict way it looks now, it sometimes seems like working on anime is more pain than pleasure! I prefer to have joy in making animation.”

Yuasa’s name is familiar to many anime fans today. In recent years, much of his “signature” anime have become available in Britain, series such as The Tatami Galaxy, Ping Pong and Devilman Crybaby, and films such as Mind Game and The Night is Short, Walk on Girl. In terms of commercial popularity, Yuasa once said that he saw The Tatami Galaxy, broadcast in 2010, as his “breakthrough.” However, he’d been working in anime for more than twenty years before that, and many of Yuasa’s fans adore his pre-breakthrough work.

If you’re surprised by how naïve and “childish” Kaiba looks, then reflect that Yuasa cut his teeth working on children’s anime in the 1990s. In particular, he animated for two long-running children’s cartoons that are almost unknown in Britain – Crayon Shin-chan, about a brattish little boy, and Chibi Maruko-chan, about a nicer little girl. By Yuasa’s own account, they were a heavy creative influence on his style. There’s an excellent montage of this early work on YouTube, set to the song “Dancing on the Inside”, full of tumbling figures and crazily whirling perspectives.

“[Crayon Shin-chan and Chibi Maruko-chan] both have really simple animation,” Yuasa told me when I interviewed him in 2017. “Especially with the actions and motions, we could actually play around a lot in these series. Because the pictures are quite simple, and easy to draw in a way, you could make it more complicated if you want to, so that’s why it was very creative to work on these animations. From a directing point of view, the stories were based on everyday life, but you could be quite adventurous within that frame, which I think was also interesting.”

Yuasa animated on several Crayon Shin-chan films, as well as on Ghibli’s My Neighbours the Yamadas, fortuitously the Ghibli film nearest his own sensibility. That was followed by Yuasa’s own film directing debut in 2004, with the psychedelic Mind Game, made by Studio 4°C. Many anime fans and professionals rated the film a masterpiece, but it was not a box office success. According to Tokyo Weekender, Yuasa said: “while he received praise, others told him the film was too confusing or boring for mass audiences.”

Mind Game earned Yuasa the tag of an “experimental” animator, although the director claims not to think of himself in those terms. I asked him if he was frustrated by mainstream, repetitive, animation, and if he was fighting against those styles to tempt people into watching something different. “Actually, I want to make something that can appeal to the mainstream audience,” Yuasa said. “But I want something that I, as a member of the audience, would find fresh but not necessarily drastically different: That’s new and nice or I haven’t seen this for a long time.”

After Mind Game, Yuasa turned to television to develop his vision. There, he made three TV shows with the Madhouse studio: Kemonozume, Kaiba and The Tatami Galaxy. Of those, Kemonozume and Kaiba were broadcast on the WOWOW satellite channel, which had given a home to the uncut Cowboy Bebop series after it was truncated on Japanese network TV. More recently, WOWOW had also screened Madhouse’s sinister 2004 series Paranoia Agent, directed by Satoshi Kon.

Whereas many of Yuasa’s anime are adaptations, Kemonozume and Kaiba were original creations by Yuasa. Kemonozume, not available in Britain yet, is a horror series about flesh-eating monsters, with a graphic style leaning toward gekiga manga. Kaiba was a radical change in direction, towards softness, roundness and pliability. While it was certainly an adult show, involving sex and death, there’s a far more childlike sensitivity to it.

For all their craziness, most of Yuasa’s anime start off grounded in present-day Japan and ordinary people. Kaiba is completely different. It’s an otherworld; it has a completely fantastical setting and set-up. Its story might be happening in the far future, or in an alternate universe. Like Tatami Galaxy, Kaiba gets easier for viewers to grasp as it goes along, though many of the main story questions aren’t answered till the last episodes.

Although there’s a lead character in Kaiba, this person doesn’t know who he is. He’s not even always “he,” going through different names and bodies! For the purposes of this article, we’ll call this person Kaiba, one name that the character is given. Apart from being confused like us, Kaiba is not made “relatable” to the audience. It’s not that kind of show; Yuasa wants us to embrace the mystery, the oddness, and the texture of its world.

Kaiba is set in a dystopian cosmos where people have found new things to buy and sell: bodies and memories. If you’re rich, you buy the body of someone poor and move your mind into it. Or you can buy a robot body. Even more enticing, you can delete your bad memories and replace them with good memories from another person. For the privileged, it’s all so much nip and tuck.

As early as episode 2, Kaiba himself has his mind poured into an inflatable hippo body. That’s lucky, given what happens to his “original” body a few moments later, at the hands of its woman owner. It’s a cute body, after all. We see nothing graphic, but this show about bodies isn’t shy about showing what bodies do.

Both innocently and carnally, this is a bouncy anime. Bodies and backgrounds, even planets, feel pliable and stretchy. Kaiba feels like it would squeak if you pressed it. The first half of the show is episodic, with the bewildered Kaiba travelling from one planet to the next, meeting people who turn out to have sad stories shot through with beauty. There’s a little girl resigned to losing her body; a mad designer of bodies who lives out an endless, fabricated rebellion; and an old woman in a lighthouse who’s both wise and deluded.

Some of these stories, especially the lighthouse one, evoke the French children’s classic The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. The story is beloved in Japan; it was also a major reference point in the anime film I Want to Eat Your Pancreas. Kaiba’s later episodes go back to the divided world where the story began, with lots of twisty reveals involving memories.

That’s not new in anime – even among mainstream movies, Ghost in the Shell, Your Name and Spirited Away all have memories being faked, shared or stolen. Another bit in Kaiba with cloned bodies feels very Evangelion. But Yuasa has always had a particular interest in escaping the constraints of the linear self. In that way, Kaiba’s journey is like those in Mind Game and Tatami Galaxy.

Other pundits have noted that Kaiba’s look seems exceedingly retro. The simple cartoon figures don’t feel that far from Osamu Tezuka. Nor does Kaiba’s combo of cuteness and tragedy, and indeed the whole idea of people being turned into commodities recalls Tezuka’s oppressed world of robots in Astro Boy. Madhouse revived these robot stories and Tezuka’s retro designs only a few years before Kaiba, in its 2001 film Metropolis.

Kaiba’s cartoon design doesn’t feel much like Yuasa’s later anime; it’s more like his work for Crayon Shin-chan and Chibi Maruko-chan. You could also put it on a continuum of world animation. Aside from Tezuka, you could align Kaiba with the 1960s anime of Cyborg 009, or with some of the ungainly adult animation of America’s Ralph Bakshi (Heavy Traffic). In its love of strange-drawn perspectives, Kaiba even has kinship with today’s family work by Ireland’s Tomm Moore (Wolfwalkers).

In Yuasa’s own oeuvre, Kaiba feels closest to some of his one-offs that also explore strange otherworlds: “Happy Machine,” from the Genius Party anthology, and Yuasa’s Space Dandy story (the season two episode, “Slow and Steady Wins the Race”). Kaiba’s inflatable hippo body anticipates a similar memorable prop in Yuasa’s film Ride Your Wave. Even a strange scene in Kaiba’s first episode, where bodiless faces rotate on a metal cog, speaking in the voices of the people they used to be, anticipates a grisly scene in Devilman Crybaby where the faces of a monster’s victims appear on its back, screaming for help. The latter image was taken from Go Nagai’s original Devilman manga, which Yuasa adores.

Kiyoshi Yoshida’s score for the series masterfully matches its helter-skelter swerves and strangeness. A couple of years earlier, Yoshida had composed the score for the Madhouse film The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, directed by Mamoru Hosoda. He’d later go on to score the Chinese animated fantasy film Big Fish and Begonia.

Kaiba’s three main characters also have familiar Japanese voices. The boy who’s sometimes called Kaiba is voiced by Hoko Kuwashima, who voiced Sango in Inuyasha, Clare in Claymore and the tempestuous Flay in Gundam Seed. Popo, another boy, is voiced by Romi Park, most famous as Edward Elric in Fullmetal Alchemist; she’s also Hange in Attack on Titan and the hero Loran in Turn A Gundam. Neira, Kaiba’s main girl character, is voiced by Mamiko Noto, whose other roles include Aisa in A Certain Magical Index, Mavis in Fairy Tail and Shinji in Full Metal Panic!

Two of Kaiba’s staff would become prominent Yuasa collaborators. One was Kaiba’s character designer Nobutake Ito, who’d first worked with Yuasa as an animator on Mind Game; he worked on the unforgettable finale where the heroes race down a whale’s throat. After Kaiba, Ito would design characters through the very different styles of Tatami Galaxy and Ping Pong and he went on to become the character designer and animation director on Yuasa’s INU-OH.

Meanwhile, Eunyoung Choi was episode director on Kaiba episode 5 – the “mad designer” episode – and episode 8. She also wrote episode 5 and was storyboarder and animation director on both those episodes. In 2014, six years after Kaiba, she and Yuasa co-founded the studio Science Saru. Choi would become its President and CEO in 2020. Speaking about Choi, Yuasa told me: “I think we are sort of looking in the same direction, but we are, in fact, pretty much polar opposites. When we decided to set up [Science Saru], that was the reason why we chose each other, because she’s the harshest critic I have. She can actually say no to me, and I normally accept that.”

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films. Kaiba is released in the UK by Anime Limited.

Leave a Reply