Mary & the Witch’s Flower

May 4, 2018 · 1 comment

By Andrew Osmond.

Two years ago, the British film magazine Little White Lies interviewed director Hiromasa Yonebayashi, then best known for directing Ghibli’s Arrietty and When Marnie was There. Yonebayashi was asked about the first Ghibli films he saw. Nausicaa and Totoro, he answered. “I’ve been watching all of them since I was a child… then eventually I joined the Ghibli team and I was building one of these worlds for them. That was a wonder. The history of Studio Ghibli is also a history of myself, from childhood to this very moment.”

Two years ago, the British film magazine Little White Lies interviewed director Hiromasa Yonebayashi, then best known for directing Ghibli’s Arrietty and When Marnie was There. Yonebayashi was asked about the first Ghibli films he saw. Nausicaa and Totoro, he answered. “I’ve been watching all of them since I was a child… then eventually I joined the Ghibli team and I was building one of these worlds for them. That was a wonder. The history of Studio Ghibli is also a history of myself, from childhood to this very moment.”

This tribute might not have impressed the crusty director of Nausicaa and Totoro. Hayao Miyazaki seems to hate the idea of people, especially kids, watching his films avidly, rather than playing outdoors. He’s also said that anime artists should observe real people, not other anime. The relationship between fandom and creation is awkward; if fans revere an idol, will they only copy that source of adoration? Miyazaki’s Kiki warns against this, when the artist Ursula says, “I painted and painted but none of it was any good. They were copies of paintings I’d seen somewhere before… I’d swore I’d paint my own pictures.”

It’s especially pertinent now Yonebayashi has directed his first feature outside the Ghibli studio, which looks phenomenally like a Ghibli film. Mary and the Witch’s Flower is the first feature of the new Studio Ponoc, which was founded in 2015 when Ghibli looked all but dead. Like “Ghibli”, taken from a Libyan-Arabic word for a desert wind, Ponoc’s name is non-Japanese – it’s a Serbo-Croat word for midnight, but also implies the start of a new day.

You could file Mary as a quasi-Ghibli production next to The Red Turtle and Ronja the Robber’s Daughter. Both were branded “Ghibli” but the studio didn’t make them. Mary definitely isn’t Ghibli, but looks closer to it than either. To be precise, Mary looks like Miyazaki’s Ghibli. Anime connoisseurs may prefer the films by Takahata, which have no house style, or the studio’s non-fantasy life-slices by other directors. But Ghibli’s public image, both in Japan and abroad, is defined by Totoros and Stink Gods and wolf princesses.

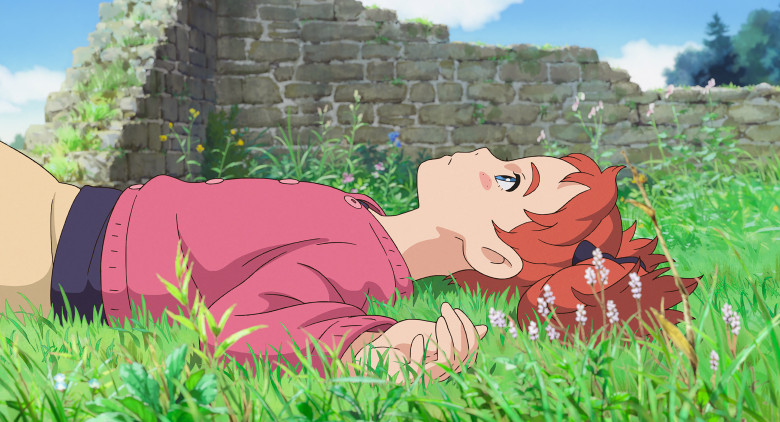

Mary is a family fantasy about a girl who finds a magic world, as Chihiro does in Spirited Away. Like Yonebayashi’s Ghibli films, Mary is based on a British children’s book; namely The Little Broomstick by Mary Stewart, published in 1971. But while Yonebayashi’s past films transposed British stories to Japan, Mary is actually set in England. It’s Shropshire, full of damp green watercolour forests and handsome houses and lanes and paths leading into mist. Like Studio WIT’s recent TV anime The Ancient Magus’ Bride, which uses similar scenery, Mary will have the effect on Londoners that Totoro had on Tokyoites – tempt them to give urban life a break and head out to the country.

Mary is a family fantasy about a girl who finds a magic world, as Chihiro does in Spirited Away. Like Yonebayashi’s Ghibli films, Mary is based on a British children’s book; namely The Little Broomstick by Mary Stewart, published in 1971. But while Yonebayashi’s past films transposed British stories to Japan, Mary is actually set in England. It’s Shropshire, full of damp green watercolour forests and handsome houses and lanes and paths leading into mist. Like Studio WIT’s recent TV anime The Ancient Magus’ Bride, which uses similar scenery, Mary will have the effect on Londoners that Totoro had on Tokyoites – tempt them to give urban life a break and head out to the country.

Mary Smith lives in her great-aunt’s cottage while her parents are away. The exact circumstances are vague, but it’s an excuse to put Mary into the starting point of many child protagonists, in a strange place at a loose end. Mary encounters an annoying boy her own age; a nonchalantly indifferent cat (which turns out to be one of a pair); and some striking blue flowers in the nearby woods. She also finds a hidden broomstick which whisks her up to the heavens and to a floating island any Ghibli fan would have to call Laputan in appearance. It serves as the base for a magic school, whose staff is convinced Mary is a wondrous prodigy. But the story doesn’t proceed as you’d expect…

In a previous article, I wondered if Japanese viewers might find Mary outmoded in the age of Your Name. Since then, I’ve seen it subbed and dubbed – the dub’s splendid, full of real British accents, from Jim Broadbent as a mad scientist to Ewan Bremmer (Trainspotting’s Spud) as a hairy Scots groundsman. But I stand by my earlier comments, especially the worry that Mary may be too slow to connect with Japanese youngsters who flocked to Your Name. Jasper Sharp’s report on Japan’s box-office in 2017 confirms that Mary broke no records; it never made the number one spot and earned barely a quarter of the Japanese takings of Beauty and the Beast. Outside Japan, the standard is set by Pixar’s Coco, another story of a child in a fantasy world, spirited via the Day of the Dead.

Nonetheless, Mary is solid, entertaining, beautiful to watch, and extraordinarily close to Ghibli. As a Ghibli fan since the 1990s, I would have flunked the taste test; if someone had removed the Ponoc logo, I would have sworn Mary was by the studio of Arrietty and Totoro. In my earlier article, I mentioned some obvious names carried over from Ghibli, such as Animation Director Takeshi Inamura and Yonebayashi’s co-writer Riko Sakaguchi (Kaguya). Beyond that, many of the key animators are Ghibli heavyweights, including – yet again – Masashi Ando, who did much to define Spirited Away, Marnie and Your Name, and mad animator genius Shinya Ohira.

Nonetheless, Mary is solid, entertaining, beautiful to watch, and extraordinarily close to Ghibli. As a Ghibli fan since the 1990s, I would have flunked the taste test; if someone had removed the Ponoc logo, I would have sworn Mary was by the studio of Arrietty and Totoro. In my earlier article, I mentioned some obvious names carried over from Ghibli, such as Animation Director Takeshi Inamura and Yonebayashi’s co-writer Riko Sakaguchi (Kaguya). Beyond that, many of the key animators are Ghibli heavyweights, including – yet again – Masashi Ando, who did much to define Spirited Away, Marnie and Your Name, and mad animator genius Shinya Ohira.

The animators also include Hideki Hamasu (who drew Kusanagi tearing up the tank in Ghost in the Shell), Shinji Otsuka (who animated Hana in Tokyo Godfathers), Atsuko Tanaka, Eiji Yamamori and others. As for background art, Ponoc’s founder Yoshiaki Nakamura – who himself produced several Ghibli films – explained in an interview how he worried Ghibli artists would “scatter” after Marnie. But they were gathered up in a new company, Dehogallery, founded with the help of Hideaki Anno.

But is this continuity no more than copying? Certainly Mary has a surfeit of images that seem very close, not just to a Ghibli “style”, but to specific images from Miyazaki-Ghibli films. The most obvious borrowings are from Kiki, Laputa and Howl, perhaps in that order. It’s no knock on Mary to say it’s not up to their level, but it does mean viewers are being constantly reminded of better works. One critic, David Ehrlich, deemed Mary a “cheap Ghibli knockoff” with a “bootleg vibe”. The “cheap” part is silly taken literally – has he looked at Mary’s animation? – but perhaps a plagiarised aesthetic is no aesthetic at all.

For myself, I found Mary’s story and characters sufficiently engaging to find the Ghibli borrowings enjoyable, not irksome. Mary is no cipher; she has her own reactions and foibles, as Anna and Arrietty did in Yonebayashi’s past films. The non-human characters are excellent, from the surly black cat Tib to the manically bouncy magic broom. Mary’s story is straightforward, perhaps more than any of Miyazaki’s films since Kiki, with none of the hazy left turns or emotion-trumps-logic of Spirited Away or Howl. Some viewers may mourn the lack of “strangeness” in Mary; others may find it a relief. I found it a well-paced and structured story with an ethos shown not told, especially in a charming, funny strand concerning Mary’s sensitivity about her red hair – it’s paid off in a climactic switcheroo that needs no words.

Notably, this strand is absent from the source Mary Stewart book, on which the film improves substantially. Many of the details are in the book, from a little dog called Confucius to the flocking animals of the climax. However, much of the last act is entirely new, as is the dramatic pre-titles prologue and backstory. The book introduces a boy, Peter, late in the book in clumsy fashion, but the film integrates him much better. The magic school in the book is very different. It’s darker and more sinister, echoing with distorted nursery rhymes, but it’s far less vivid than Stewart’s descriptions of nature (“Everywhere was damp, and decay, and the end of summer”) and of flying (Mary’s broomstick spears into cloud that’s “a whirling, tossing mass of lighted foam.”)

The film keeps the nature and flying and fortifies the school, especially in some lively glimpses of student life that let the animators have fun but set up a Lemony Snicket-style joke; this is not the film we’re going to stay with. The flying island may suggest Laputa, but I found it more reminiscent, pleasantly so, of the magic realms often visited by Rupert Bear. Some elements of Mary’s expanded plot parallel – but not derivatively – the stop-motion Coraline, with it and Mary sharing ornate gardens that look very different after sundown. An elevator carrying Mary through the magic school feels like one in the vertical world of The King and the Mockingbird, a classic French cartoon that hugely influenced Miyazaki.

The film keeps the nature and flying and fortifies the school, especially in some lively glimpses of student life that let the animators have fun but set up a Lemony Snicket-style joke; this is not the film we’re going to stay with. The flying island may suggest Laputa, but I found it more reminiscent, pleasantly so, of the magic realms often visited by Rupert Bear. Some elements of Mary’s expanded plot parallel – but not derivatively – the stop-motion Coraline, with it and Mary sharing ornate gardens that look very different after sundown. An elevator carrying Mary through the magic school feels like one in the vertical world of The King and the Mockingbird, a classic French cartoon that hugely influenced Miyazaki.

There’s also a rather fascinating dimension to Mary’s adaptation that may have been unintended, or only meant as a small point. The Little Broomstick was published a quarter-century before Harry Potter, yet for a time the film seems destined to become a Potter-style story of a girl enrolling at a magic school. But instead, Mary subverts our expectations of stories of student wizards with preset destinies. Indeed it seems to link such stories with dangerous power fantasies! At least Mary is easily read that way, though with deniability; there are no cheap jokes about lightning-shaped scars.

Intended or not, it makes Mary an interesting reflection of how British children’s literature has changed over the decades, and how anime is preserving its heritage from the other side of the world. Like the book of When Marnie was There, The Little Broomstick was long out of print in Britain before the anime adaption – unsurprisingly, a new edition has appeared with a “Now a motion picture” tag. It’s also notable that this anti-Potter anime comes soon after Studio Trigger’s hilarious series Little Witch Academia, which also pokes fun at magic schools and “chosen one” narratives. According to its director Yoh Yoshimari, the British-set anime was partly inspired by him seeing The Worst Witch on TV – which was based on another pre-Potter vintage British kids’ book, published just three years after The Little Broomstick.

Mary has opened in America and enjoys a healthy Rotten Tomatoes score, though lower than Yonebayashi’s Ghibli films. Personally, I think Mary challenges Arrietty, though I found the subtle, sombre Marnie more interesting than either, and the most convincing evidence that Yonebayashi can break out of Miyazaki’s shadow. Now, of course, Miyazaki himself is back in the picture, prepping his feature How Do You Live? and it seems Ghibli may be soon back in full production, taking away any sense that Ponoc is its closest inheritor. But will Yonebayashi, or another director, be bold enough to take Ponoc’s Ghibli-derived skillset and draw pictures that are indisputably its own?

Mary and the Witch’s Flower is released in UK cinemas this month.

Andrew Osmond, anime, cinema, Hiromasa Yonebayashi, Japan, Mary and the Witch's Flower, Mary Stewart, Studio Ponoc

Liam Quane

May 6, 2018 2:31 pm

I understand that real, pure, natural inspiration can be a good influence but we don't live in a time where collecting insects was the only hobby most children can afford. Miyazaki is perfectly within his own right to criticise modern filmmakers for ther influences (he doesn't have to be so sociopathic in his approach like The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness shows him being.) There doesn't have to be one way of doing things, it's only in the subjective "pudding-tasting" that quality becomes to x-factor when it comes to a film's reputation.