Memories: Stink Bomb

August 25, 2022 · 1 comment

By Jonathan Clements.

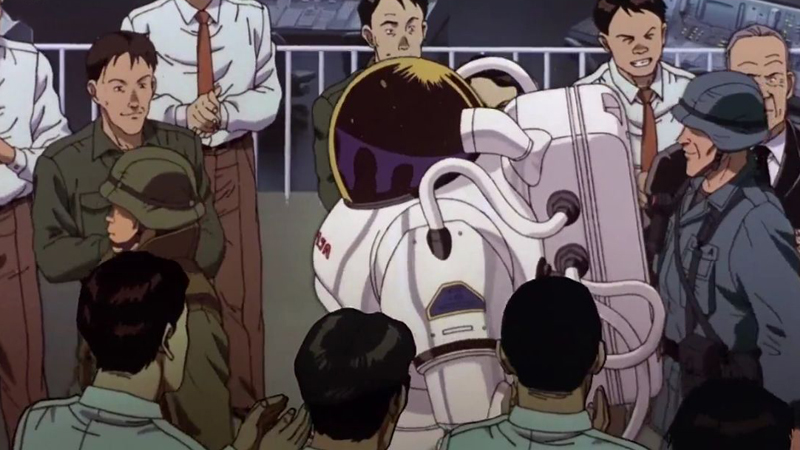

Hapless lab assistant Nobuo Tanaka is working on a new ‘miracle drug’ at a research institute. Unfortunately for him, his harmless project turns out to have a military dimension, and when Tanaka mistakes a stray pill for a cold remedy he fails to realise he has just become the ultimate weapon. Now he emits a gas that kills every living creature within range, but makes flowers grow, even in winter. Doggedly following orders to report to the Tokyo office, Tanaka doesn’t quite understand why the armies of the world will do anything they can to stop him.

Suddenly, we are in the country town of Yamanashi, a world away from the apocalyptic space bombast of the finale of Magnetic Rose. But that is all part of the plan, in the chapter of the Memories anthology movie that was fated to be stuck in the middle.

“In terms of quality,” admits director Tensai Okamura, “it was abundantly clear that the other two were going to be to be brilliant, so to be honest, I didn’t want to try to compete with them on a level playing field.” Instead, he deliberately brings the film crashing back down to Earth, from the deep space ending of Magnetic Rose, to the sleepy provincial town of Yamanashi.

“We needed the topography of a basin, adjacent to the Kanto Plain,” says Okamura, “a basin where Tokyo would be on the other side of the mountains.” But Yamanashi was not merely a convenient location. It was also the setting for one of the inspirations for Katsuhiro Otomo’s original script, Juko Nishimura’s Horobi no Fue (The Whistle of Destruction). Published in 1976, it features an ecological catastrophe in Yamanashi, when the local rat population reaches epidemic proportions after a rapid proliferation of bamboo grass. In subsequent novels in the series, this turns out to be only the first of a cascade of escalating disasters, as humanity faces multiple threats, uncovering the degree to which human governments and agencies are ill-equipped to cope. Yamanashi, in Nishimura’s series, is not merely a town in the mountains, but the flashpoint of a crisis that eventually envelops the whole world.

The other, more obvious inspiration was an unsolved real-world mystery from 1994, the so called “Toxic Lady” case in Riverside, California. The dying cancer patient Gloria Ramirez was admitted to hospital suffering from heart palpitations. As staff tried to administer treatments to her, several noticed a strange “fruity, garlic-like smell”, an “oily sheen” on her skin… and then people started to faint. It had been speculated that Ramirez had been self-administering dimethyl sulfoxide as a home-made pain remedy, which was transformed into toxic dimethyl sulphate by the electric shocks administered by medics through a defibrillator. However, the Ramirez case, written off by some as mass hysteria, has never been entirely explained. Stink Bomb extrapolates it into a military conspiracy in the vein of The X-Files, which also aired an episode in 1994, “The Erlenmeyer Flask”, drawing on elements of the Ramirez case.

“Rather than the protagonist’s actions, I wanted to depict how the Japanese state might deal with such an emergency,” says Okamura. “Like, the fire services get involved, and the police get involved. In the end, I omitted those processes, so I was wasn’t able to concentrate as much as I wanted to on how much they would lack the capacity to cope with crises. That is something I wanted to do more.”

Okamura alludes to the difficulties of cramming everything he wanted to say in a movie-length story but was restricted to a running time of 40 minutes. Watching the film in hindsight, it is easy to sympathise with his frustrations, that the necessary ten-minute set-up eats up a quarter of his allotted footage, thereby forcing him to cut his planned sequence of panics and misunderstandings all along the chain of command. Instead, he sighs, “it all went to the top brass in no time, so you could say I wasted that opportunity.”

Okamura had come up through ranks at the Madhouse studio as an inbetweener, and then as key animator on works including Wicked City and Ninja Scroll. Today, he is best known as the originator and show-runner on Darker than Black, but on Stink Bomb he was a rookie director for the cinema, fretting that he would suffer the embarrassment of over-running.

“When the production manager ran the numbers, he told me that we were ten minutes over,” he recalls. “I panicked, thinking that couldn’t be true. But come to think of it, when I watched the rushes, every single shot felt heavy and I thought it went over quite a lot, but when I asked the editor, it was 42 minutes. It was just fine. I still ended up dropping some shots because I believed we were over-running, but it turned out in the end to be a miscalculation!” The final cut of his film runs with watchmaker’s precision to 40 minutes on the dot, plus 14 seconds of black to separate it from the next film. Considering that supervising director Katsuhiro Otomo’s Cannon Fodder substantially over-ran (what we might call the show-runner’s prerogative), Okamura can be proud of his obsessive time-keeping.

The young Okamura also demonstrated an ardent ambition, exploiting the fact that the Madhouse studio had its own multi-plane camera. Instead of sending cels away to be composited, he found the irresistible urge to tinker with complex images, such as the bustling activity at the military command centre. “In some shots,” he admits, “we used six or seven planes [of movement]. As each cel has a depth to it, there are inevitably shadows.” Usually, that’s not the sort of risk an animator would take, since every issue with an image would involves calls back and forth between the compositors, some of whom could well be as far away as Seoul, and a director. But Okamura made himself fussily available on-site, ready to experiment with increasing or reducing layers – “I took things to the ultimate limit, so I think I really annoyed the filming staff.”

Stink Bomb remains an under-appreciated gem within the Memories anthology, an action caper over-shadowed by the two heavy hitters that bracket it. It’s also a film with an odd knack of catching the zeitgeist. Okamura himself ruefully notes that he and his crew were mixing the big-band soundtrack and bickering over how to model smoke and fumes in March 1995, when televisions began broadcasting newsflashes about the infamous Aum Shinrikyo sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway. He remembers it as “more scary than surprising” because of the number of real-world coincidences. “When I saw the police investigators, for example, they were all tramping around in the snow in Yamanashi. And that aerial shot as the guru [Shoko Asahara] was being transported along the Chuo Highway was just the same as we’d done it.”

Revisiting the film in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s surprising how many resonances seem very much of our time. Stink Bomb begins in a doctor’s surgery, as the sniffling Tanaka gets his flu jab, and locals grumble about the virus that’s going around. He walks out into the snowy streets wearing a face mask – an entirely everyday sight in 2022, but something of an Asian peculiarity in 1995. The custom of wearing a medical mask when ill to protect others, was commonplace in Japan, China and South Korea, but had yet to spread around the world.

Stink Bomb was not the first Otomo project to feature an unlikely militarised chase after an unsuspecting target. His earlier Roujin-Z winningly turned an old man’s desire to see the seaside into a chaotic cross-country chase as the authorities try to bring down a “robot bed” that is really a military prototype. Here, too, we have an everyman who is largely unaware that he is the problem everybody is trying to solve, and Okamura takes evident glee in his grand set-pieces of the army in action, to the point where one critic observed he was creating a “mecha crowd scene”, teeming with tanks.

Mr Tanaka’s tribulations are rendered all the more comedic by the fact that it’s his sweat that is found to be causing the noxious vapours. There is a stand-off prefiguring the ironies of the recent satire Don’t Look Up, as the US military’s desire to make good on its development investment over-rides the need of the Japanese government to neutralise the problem in the most effective, but lethal, means possible. Contending forces want to kill Mr Tanaka or take him alive, and either way, they’re sure to make his stress levels climb through the stratosphere.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History. Katushiro Otomo’s Memories is available for pre-order from Anime Limited.

Zali

March 13, 2023 8:26 am

I thoroughly enjoyed this segment of the anthology. It was Akira all over again and resonates with the recent pandemic. The sheer helplessness of the authorities, despite mobilising the entire JSDF and every resource available to them to stop one guy's noxious farts was humbling. Contrast this with how humanity eventually wins out in Shin Godzilla and Shin Ultraman, the clinically efficient and effective bureaucracy and military professionalism on display dealing with otherworldly monsters as if they were nothing more than natural disasters versus the utter chaos and SNAFU of throwing everything and the kitchen sink dealing with the unknown in "Stink Bomb". Quite different visions.