Mifune: The Last Samurai

February 26, 2019 · 0 comments

by Jeremy Clarke.

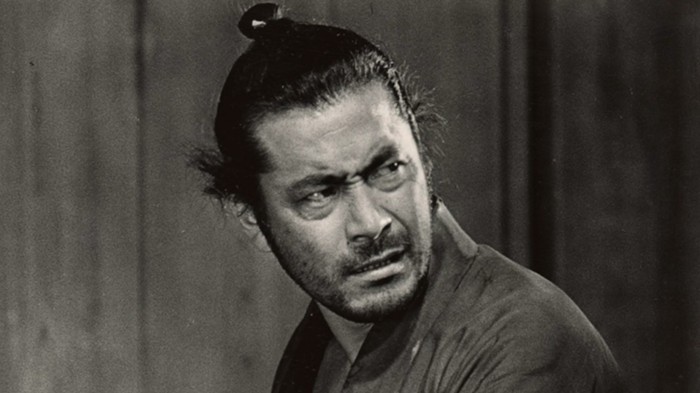

Toshiro Mifune (1920-1997) is director Akira Kurosawa’s iconic star of his samurai movies Rashomon, Seven Samurai and Yojimbo. He’s the subject of three time Oscar-nominated documentary film maker Steven Okazaki’s useful documentary Mifune: The Last Samurai (2015). As narrator Keanu Reeves says in voice-over, without Mifune there would have been no Magnificent Seven, Eastwood would not have had A Few Dollars More and Darth Vader would not have been a samurai.

Toshiro Mifune (1920-1997) is director Akira Kurosawa’s iconic star of his samurai movies Rashomon, Seven Samurai and Yojimbo. He’s the subject of three time Oscar-nominated documentary film maker Steven Okazaki’s useful documentary Mifune: The Last Samurai (2015). As narrator Keanu Reeves says in voice-over, without Mifune there would have been no Magnificent Seven, Eastwood would not have had A Few Dollars More and Darth Vader would not have been a samurai.

The documentary spends a good twenty minutes on background Japanese history, early Japanese film and Mifune’s life before his career in movies began. Among other things, this means lots of enthralling clips of silent chanbara (period swordplay movies). Mifune was born to Japanese parents in China; he grew up helping at his father’s photographic studio. At age 20 he was drafted and sent to Japan.

The slightly younger actor Takeshi Kato who later worked alongside Mifune on several of Kurosawa’s films recalls being schooled as “little citizens, children of the Emperor who must be prepared to die for him.” Mifune’s son Shiro relates how his father was required to train pre-pubescent boys to fly suicide missions, telling them not to say “Banzai!” for the Emperor as per official requirements but rather to just say goodbye to their own mother. Mifune’s parents didn’t survive the war and there’s no record as to exactly when or how they died.

Demobbed after the war with one and a half yen and a blanket which he turned into a coat, Mifune was desperate for work. He got into movie acting by accident, having originally applied to work at Toho Studios as a camera assistant. Kurosawa spotted him there, immediately recognised a unique quality and decided he wanted to work with him as an actor. The pair would go on to make sixteen films together.

Rashomon’s winning the Golden Lion at the 1951 Venice Film Festival catapulted director, star and indeed Japanese cinema into the international spotlight as never before. At the time, Kurosawa did not command the same respect back in his homeland. According to Mifune when interviewed for a Guardian Lecture at the NFT in 1986 which can be found as a 60-minute alternate audio track on the DVD, Rashomon only made it to Venice as a fluke having been selected by Japanese film export people with little knowledge of what they were doing. A cynical Daiei executive sold Rashomon to Hollywood’s RKO Radio Pictures cheap, which made RKO quite a bit of money. The same executive who’d previously thought the film worthless then changed his mind and attempted to replicate Rashomon’s success by producing a series of unremarkable and today long-forgotten Kyoto gate movies.

For those unfamiliar with Rashomon, its period tale of woodland rape and murder charts the story of a bandit (Mifune) and a travelling husband and wife couple who become his victims. The tale is related from four different characters’ contradictory viewpoints, one after the other, forcing the audience to come to its own conclusions as to what actually transpired. Among the many elements that mark Rashomon out for greatness is Mifune’s performance. In preparation for his role, the actor studied the movement of lions. He’s “like a caged animal” according to the ever-enthusiastic Martin Scorsese.

For those unfamiliar with Rashomon, its period tale of woodland rape and murder charts the story of a bandit (Mifune) and a travelling husband and wife couple who become his victims. The tale is related from four different characters’ contradictory viewpoints, one after the other, forcing the audience to come to its own conclusions as to what actually transpired. Among the many elements that mark Rashomon out for greatness is Mifune’s performance. In preparation for his role, the actor studied the movement of lions. He’s “like a caged animal” according to the ever-enthusiastic Martin Scorsese.

Mifune and Kurosawa’s joint career continued through Seven Samurai (1954), Throne of Blood (1957), Yojimbo (1961) and Red Beard (1965). Clips from and discussion of Rashomon and these other four films will make you want to sit down and watch them. Restricting the in-depth discussion to those five Kurosawa films only is a smart move since it not only enables satisfying segments on each but also allows time to adequately sketch the wider contexts of both Mifune and, to a lesser extent, Kurosawa’s subsequent careers.

Seven Samurai, in which poor farmers hire warriors to protect their village against bandits, is arguably the greatest action film ever made. According to Mifune it was originally to have been Six Samurai until Kurosawa decided that a seventh was needed to bridge the gap between samurai and peasants. The seventh was conceived as a Joker card. “I was told to play that any way I wanted,” he says with relish. Hollywood remade Seven Samurai as The Magnificent Seven and Italy Yojimbo as A Fistful of Dollars. Throne of Blood rehashes Macbeth in period Japan and recently topped a poll of Shakespeare movie adaptations. Actress Yoko Tsukata, picked out by red lettering in a Yojimbo fight sequence clip, talks about Mifune’s generous treatment of women on set. Stuntman Kanzo Uni, killed onscreen by Mifune more than 100 times, is similarly highlighted in a Red Beard clip as one of several thugs battling the actor. Uni is particularly good value with a lot of stories to tell.

There’s not much on post-1965 Kurosawa beyond mentions of his later works without Mifune, such as Kagemusha (1980). His highly regarded Ran (1985) doesn’t even get a look in. The 20 minute Steven Spielberg interview supplied as a disc extra also mentions Dreams (1990) for which Spielberg secured the finance. We hear part of Kurosawa’s moving letter sent to Mifune’s funeral which the director himself was too ill to attend. He died a year after his star in 1998.

Additionally mentioned in passing are further Kurosawa/Mifune collaborations, other Japanese films and a handful of international movies. The first group include Snow Trail (director Senkichi Taniguchi, screenplay Kurosawa, 1947), Star Wars inspiration The Hidden Fortress (1958) and crime thriller High And Low (1963), the second, Hiroshi Inagaki’s Samurai Trilogy (1954-6) and the third, John Boorman’s Hell In The Pacific (1968) and Steven Spielberg’s 1941 (1979). Spielberg calls the actor unique and says that no-one can imitate him, though many actors study his work closely.

Some two decades after Mifune’s last film for Kurosawa, 34-year-old Steven Okasaki came across him in 1986 at a party hosted by the Hawaii International Film Festival. Mifune was the film-maker’s favourite actor since seeing Seven Samurai at age 11 which for the boy placed the actor above “John Wayne, James Stewart, Paul Newman or even Sean Connery in the James Bond movies”. Not being much of a party animal, Okazaki was hanging around the edge of the event when he noticed Mifune, drink in hand, observing the gathering from the sidelines. “I knew immediately it was him. He had perfect posture and held himself just like Toshiro Mifune would.” Thirty years on, Okazaki’s documentary is a striking piece of work likely to endear itself equally to either Mifune or Kurosawa connoisseurs on the one hand or the newcomer on the other.

Mifune: The Last Samurai is out now on iTunes and released on DVD on 18th March.

Leave a Reply