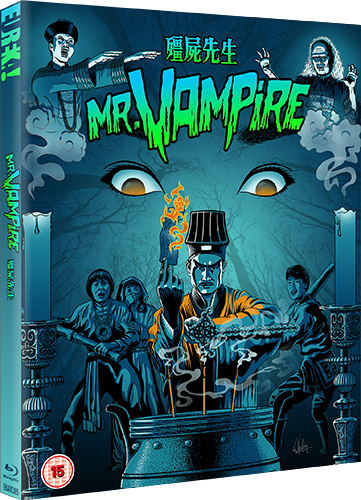

Mr. Vampire

July 21, 2020 · 0 comments

by Jeremy Clarke.

If your knowledge of vampire lore comes from Western movies about Dracula you’re in for some real surprises with the 1985 Hong Kong movie Mr. Vampire. This is the movie that put the Chinese hopping vampire on the map.

If your knowledge of vampire lore comes from Western movies about Dracula you’re in for some real surprises with the 1985 Hong Kong movie Mr. Vampire. This is the movie that put the Chinese hopping vampire on the map.

It’s evening, as mortuary assistant Man Choi (Ricky Hui) checks a number of upright standing corpses with talismans affixed to their foreheads. All present and correct. Behind him a corpse without a talisman advances towards him. By the time he’s realised this is fellow mortuary assistant Sang (Chin Siu-ho) playing a prank, the resultant air flow has blown the talismans off the other foreheads and eight vampires are hopping towards them, Man Choi runs to fetch his employer, Master Gau (Lam Ching-ying), who together with a visiting Taoist priest (Anthony Chan) bites two of his fingers to draw blood so that they can replace the missing talismans on each of the ravenous corpses’ foreheads with dual bloody fingerprints via a series of deft kung fu moves. Whew! Saved…

The ancient Chinese had a concept of ‘transporting a corpse over a thousand li’. Someone who died far from home would be reanimated by Taoist priests so that they could return by jumping along to save the family the cost of transportation. In reality, several corpses would be attached to bamboo poles carried by one man at the front and another at the back. As the pair walked along, the bamboo would flex, causing the dangling bodies to appear to hop. This gave rise to the somewhat fanciful folk legend of the jiangshi or hopping vampire.

The ancient Chinese had a concept of ‘transporting a corpse over a thousand li’. Someone who died far from home would be reanimated by Taoist priests so that they could return by jumping along to save the family the cost of transportation. In reality, several corpses would be attached to bamboo poles carried by one man at the front and another at the back. As the pair walked along, the bamboo would flex, causing the dangling bodies to appear to hop. This gave rise to the somewhat fanciful folk legend of the jiangshi or hopping vampire.

The word jiang meaning ‘stiff’, jiangshi can’t move much owing to the effects of rigor mortis. Instead they hop around with their arms outstretched in the hope of catching living humans to suck out their life force. They come out at night; during the day they hide from the light in a coffin or a cave. Depictions generally dress them in official clothing from the Qing Dynasty.

Jiangshi can be found as far back as Pu Song-ling’s story A Corpse’s Transmutation (1740). While the cinema in the West was quick to film Bram Stoker’s Victorian novel Dracula as Nosferatu (1922) in the silent and Dracula (1931) in the sound era, the Chinese were slower to put such aspects of their own culture on the screen. The Corpse-Drivers Of Xiangxi / aka The Case Of Walking Corpses (1957) employed cadavers hung from bamboo rods as a vehicle for transporting illegal drugs. It was swiftly upstaged by the international success of Britain’s Hammer Films’ Dracula (1958). Hammer later tried to crack the Chinese market with The Legend Of The 7 Golden Vampires (1974) in which, to quote critic Stephanie Lam from John Towlson’s essay in the accompanying booklet: “a Dracula movie appropriates and unfolds over the top of the image of Chinese culture, which in the 1970s was made portable and consumable in the kung fu film.”

A jiangshi made a brief appearance in director-actor Sammo Hung’s comedy horror vehicle Encounters Of The Spooky Kind (1980). Two years later, Hung starred in (and executive produced) The Dead And The Deadly (1982), set largely in a mortuary where various characters possessed others’ bodies. The po-faced Lam Ching-Ying appeared in both, as an inspector in the first and a priest in the second.

Mr. Vampire would make Lam a minor star. His serious demeanour anchors what is essentially a horror comedy, with bumbling characters unwittingly unleashing jiangshi. For the rest of his career, Lam mostly played vampire-hunting priests in jiangshi movies, including several more Mr. Vampire films. Mr. Vampire II (1986), III (1987) and IV (1988) provided more of the same but only Mr. Vampire 1992 (1992) was actually a sequel to the first film. Lam also appeared in similar fare in the form of Encounters Of The Spooky Kind II (1989), Magic Cop (1990) and Vampire Vs. Vampire (1989, directed by Lam himself). The TV series Vampire Expert (1996-7) was cut short when he died of liver cancer while shooting the third season.

One typical stunt has the Taoist priest immobilise a corpse with a forehead blood fingerprint only to realise that its hands are clasped around his neck. The only way to get the hands to release their grip is to wipe the fingerprint off the forehead and replace it with another print seconds later when the corpse’s hands have drawn back to attack. Job done. Alongside the stunts complete with humorous, cartoon sound effects comes burlesque slapstick comedy, Hong Kong-style. An extended gag later on involves Yam’s innocent daughter Ting-ting (Moon Lee in a rare, non-fighting role) being mistaken for a whore. Someone clearly thought this was funny but today it looks embarrassing.

There are three separate plots. The first features the late father of a well to do client Mr. Yam (Huang Ha) who needs to be exhumed and reburied to correct some bad Feng Shui. While dug up, he reanimates. The second involves a beautiful female ghost (Pauline Wong Siu-fung) seducing Sang, laying the groundwork for the Tsui Hark-produced A Chinese Ghost Story (1987) and sequels. The third sees Mr Yam bitten and turned into a hopping vampire. All three plots get mixed up in the course of the overall narrative.

There are three separate plots. The first features the late father of a well to do client Mr. Yam (Huang Ha) who needs to be exhumed and reburied to correct some bad Feng Shui. While dug up, he reanimates. The second involves a beautiful female ghost (Pauline Wong Siu-fung) seducing Sang, laying the groundwork for the Tsui Hark-produced A Chinese Ghost Story (1987) and sequels. The third sees Mr Yam bitten and turned into a hopping vampire. All three plots get mixed up in the course of the overall narrative.

Some culturally specific humour makes more sense after you’ve heard Hong Kong movie expert Frank Chan’s commentary, The standout element however remains the jiangshi. They’re first seen standing in a line wearing their officials’ uniforms with yellow paper talismans bearing written spells affixed to their foreheads to render them immobile. Once these talismans blow off or are otherwise removed the jiangshi hop with arms outstretched after any person unlucky enough to be nearby. Only the likes of Master Gau can stop them.

Although much research was done into customs relating to jiangshi, the yellow talisman appears to have originated with the scriptwriters. This became such an effective trope that it occasionally crops up in anime. Episode one of Devil Hunter Yohko (1990) has a demon stopped in his tracks by the affixing of a similar talisman to his forehead. Meanwhile, Mr. Vampire III, which featured an adult and a child ghost from the same family, among other things, proved hugely profitable at the Japanese box office.

The action element in Mr. Vampire felt far more enthralling in its day than the comparatively lacklustre stunts in Western cinema. That wasn’t to change until The Matrix (1999) put Hollywood actors through a Hong Kong-style action boot camp and brought that sensibility into the Hollywood mainstream. Viewed today, Mr. Vampire still holds up well. Often imitated, never equalled.

Eureka’s new disc also includes interviews with Chin Siu-ho and Moon Lee from the 2001 Hong Kong Legends DVD, plus a brand new interview with director Ricky Lau.

Mr. Vampire is released on UK Blu-ray by Eureka Classics. Jeremy Clarke’s new website is jeremycprocessing.com

Leave a Reply