Relatives for Rent

July 25, 2018 · 1 comment

By Andrew Osmond.

This April, an eye-poppingly extraordinary article about Japan appeared, not in a specialist otaku magazine, but in that august English-language journal, The New Yorker. Its opening line looks like it should start a science-fiction story, like Orwell’s clocks striking thirteen or Ballard’s protagonist eating dog in High Rise. The article, written by Elif Batuman, begins:“Two years ago, Kazushige Nishida, a Tokyo salaryman in his sixties, started renting a part-time wife and daughter.”

It’s not science-fiction. It’s a non-fiction story about what is described as “Japan’s rent-a-family phenomenon,” about Japanese agencies which rent out actors to paying clients, for a wide range of reasons. In the case of Mr Nishida, his real wife had died, his daughter had moved out, and he was lonely. So he paid forty thousand yen (about £270) to a rental company, Family Romance, and met two female actors supplied by the company, ready to behave as his wife and daughter.

Batuman writes, “The (rental) wife cooked okonomiyaki, a kind of pancake that Nishida’s late wife had made, while Nishida chatted with the daughter. Then they ate dinner together and watched television.” You can almost see the ghost of Philip K. Dick standing over the happy family, applauding.

That’s just the start. Batuman describes an actress who substitutes for overweight mothers at school parents’ evenings. The reason; “the children of overweight parents may be subject to bullying.” An actor helps out women who’ve been caught having affairs. The actor pretends to be the woman’s lover, dressed and tattooed like a yakuza to dissuade the cheated husband from getting aggressive. We read of entire staged weddings put on to deceive marriage-mad parents (we’ll talk more about this later).

For anyone whose mind has already raced into other areas, Batuman pours on some cold water. “In general, rental partners and spouses aren’t supposed to be alone with clients one on one, and physical contact beyond hand-holding is not allowed.”

The most extraordinary story is at the article’s end, and reads like the outline for a family drama by Hirokazu Kore-eda. A single mother is worried by her ten year-old daughter, who has a withdrawn personality. She calls the Family Romance agency, and hires an actor to play her long-lost dad, whom the girl’s never seen. The actor tells the girl that he, her dad, has remarried, but he still wants to see her. He turns up at the girl’s birthday parties; he takes her to Disneyland. Now the girl is nearing twenty, and still thinks this man is her father.

The article is a terrific read, a headspinning “Is this true?” experience that has the reader looking for references to 1st April or scanning the columns for a “wind-up” acrostic. You can read the full 9,500-word story here (the title is “A Theory of Relativity”) but be warned; the New Yorker website only allows non-subscribers to access five articles per month, or one article five times. The piece provoked astonished responses on Twitter, from “mouth-agape fascinating” to “one of the saddest things I’ve ever read”. There’s also been the odd dissenting note. One Tweeter pithily accused the New Yorker of “Using an outlier to perpetuate the Japan is weird stereotype.”

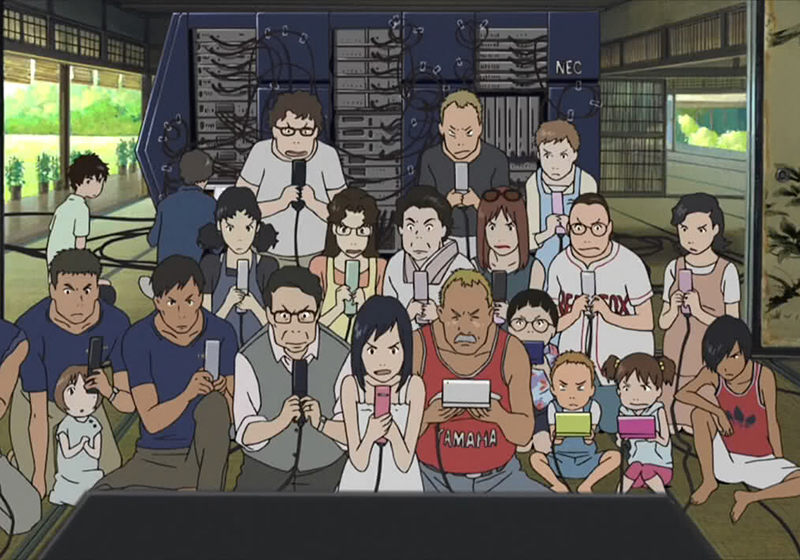

We’ll come back to that later. But the New Yorker story should feel oddly familiar to anime fans. Think, for example, of Mamoru Hosoda’s film Summer Wars. At the start of that story, our slightly nerdy boy protagonist is mysteriously asked to do a favour for a pretty girl classmate. She leads him to her family country home (actually, samurai-era fortress). Then, to the boy’s astonishment, the girl claims to her huge extended family that the boy is her fiancé. Later, she explains this charade is to cheer up her great-grandmother. If she had read the New Yorker, she could have hired a boy for the job, and a cuter catch to boot.

We’ll come back to that later. But the New Yorker story should feel oddly familiar to anime fans. Think, for example, of Mamoru Hosoda’s film Summer Wars. At the start of that story, our slightly nerdy boy protagonist is mysteriously asked to do a favour for a pretty girl classmate. She leads him to her family country home (actually, samurai-era fortress). Then, to the boy’s astonishment, the girl claims to her huge extended family that the boy is her fiancé. Later, she explains this charade is to cheer up her great-grandmother. If she had read the New Yorker, she could have hired a boy for the job, and a cuter catch to boot.

Other anime echoes include part three of Satoshi Kon’s Paranoia Agent, in which a troubled woman and her bland fiancé pay for staged photos of a church wedding they can’t afford (“It’s like actually having a wedding!”) The recent Sword Gai series on Netflix features a boy who lost his family in a car accident and hires actors to replace them, presumably from a rental family company. There’s also a touch of the idea in Pieta in the Toilet, a live-action film from an idea of Osamu Tezuka. A young man with cancer pays a schoolgirl to impersonate his sister, to fool hospital staff; so starts a prickly but genuine friendship.

Other anime echoes include part three of Satoshi Kon’s Paranoia Agent, in which a troubled woman and her bland fiancé pay for staged photos of a church wedding they can’t afford (“It’s like actually having a wedding!”) The recent Sword Gai series on Netflix features a boy who lost his family in a car accident and hires actors to replace them, presumably from a rental family company. There’s also a touch of the idea in Pieta in the Toilet, a live-action film from an idea of Osamu Tezuka. A young man with cancer pays a schoolgirl to impersonate his sister, to fool hospital staff; so starts a prickly but genuine friendship.

Then there are SF treatments of the similar themes, going back to Tezuka’s Astro Boy manga in the 1950s, about an inventor who creates a robot boy to replace his dead son. The anime Hal extends the idea, imagining androids which resemble dead people, purpose-built to help the bereaved through their grief. The hero of Phoenix 2772 (aka Space Firebird), another Tezuka-derived story, is raised from infancy by a customised android mum. The Puppet Master super-hacker in Ghost in the Shell implants memories, so that a luckless stooge treasures a loving family which doesn’t exist.

Away from SF, Bautman writes of a “substantial literary corpus” in Japan specifically about rental relatives, especially among postmodern and queer novelists. It figures in detective fiction; the mystery novelist Misa Yamamura wrote Murder Incident of the Rental Family back in 1993. According to Bautman, the first real rental family business appeared only a few years earlier, in 1989. It was run by a woman, and specialised in “renting out children and grandchildren to neglected elders.”

World media often presents Japan as if it’s already a giant simulation where rental relatives would fit right in. Japan is the country of Hatsune Miku, of robot dogs and pretend flights to Paris. Tourists see this side of Japan more than locals. I was once dragged (honestly) into an imouto “little sister” café in Akihabara, in which the waitress didn’t just wear a maid outfit, but greeted guests in character. “Hello, big brother! Have you had a good day, big brother…”

But having read the New Yorker article enthralled, I asked half a dozen Japanese friends in Tokyo if they had ever heard of agencies like Family Romance. Three said no; the rest had seen such companies mentioned on television, but knew no-one who had used them. Of course, this is a laughably small interview sample, but it’s possible that rental relative companies are very small subcultures in Japan, magnified by the media. Readers of this blog should know about those.

One of my friends was also baffled by a particular detail in the article. At one point, it refers to elaborate fake weddings, paid for by youngsters to dupe their “marriage-obsessed” parents – the costs run to tens of thousands of pounds. Batuman writes of “weddings” where “everyone is an actor except the bride and her parents”. In this, she seems to be relying on what’s she’s told by Yuichi Ishii, the founder of the company Family Romance.

But as my friend pointed out, such a deception would seem doomed to collapse in days, weeks at most. What if, for example, the parents glance at an official document about their child following the happy event? Japan is many things, but it’s not The Truman Show.

That aside, would it matter if the rental families phenomenon was a marginal subculture? It’s a hoary issue; when do subcultures reveal bigger truths, and when do they just generate great copy? Batuman argues that rental families can tell us things. Late in the article, she launches into a discussion of the ideological constructions surrounding love and family. In particular, she suggests, “the idea of a rental partner, parent or child is perhaps less strange than the idea that childcare and housework should be seen as manifestations of an unpurchasable romantic love.”

In itself, it’s a perfectly reasonable suggestion. But it’s possible that Batuman is using a Japanese “phenomenon” – a narratively engaging but maybe marginal one – to present and sell an agenda. A quick look at some previous English-language articles on rental families show other writers drawing different morals, Rorschach style.

In a Los Angeles Times article on rental families from as far back as 1992: “Behind the bright exterior of Japan’s material wealth are some pressing emotional wants… A society stressing the harmony of human relationships is in fact riddled with tensions about them.”

Or this from the Independent in 2009. “Observers say the ‘rent a friend’ trend is a sign of an accelerated deterioration in personal and professional relationships (in Japan). In the past, many companies were family-like affairs where workers spent most of their lives and knew their bosses. But the post-1990s disintegration of lifetime employment has fractured many of those bonds… A growing number of people are putting off marriage or children and leading atomised, lonely lives in cramped, lonely apartments.”

Such passages remind me of two of the “four Japans” proposed by Frederik L. Schodt in his analysis of how Japan is perceived abroad. Either rental families are a “Model,” a way to take apart Western ideological constructions, as in Batuman’s account. Or else they’re a dark “Mirror”, a cautionary tale of capitalism taking bad paths.

The argument is strangely brought home in a recent anime film that seems to offer its own oblique comment. In Studio Ghibli’s 2014 film When Marnie was There, the protagonist, Anna, is a girl with foster parents. Late in the story (slight spoiler), she reveals something she found out that traumatised her. Anna discovered that her parents receive government money to help foster her.

Ever after, Anna fears that her parents don’t really love her; in effect, they could be paid actors, playing the parts of her loving mum and dad. Are Japan’s “rental relatives” really every bit as real as it needs to be, as Batuman suggests at the end of her 9,500-word article? The irony is that Marnie isn’t a Japanese story, though it’s undoubtedly better known in its Japanese retelling. Marnie is based on a book, which comes from England.

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films.

Matthew

July 25, 2018 4:27 pm

Your webstore deals are hotter than the weather outside, good god. Wouldn't say no to some Funimation distro offers like Absolute Duo.