The Kindness of Strangers

October 28, 2015 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

Moving to a new town and a new school, sparky teenager Tetsuko Arisugawa (“Alice”) is still getting used to her new surname after her parents’ divorce. Dad is a charmer but a loser in life; Mum is a flaky author with a habit of dramatising their private life for profit. Meanwhile, her new schoolmates claim to be sinister occultists, and a dusty, empty desk in the middle of the classroom alludes to a disaster that none dares speak of. All that she can glean is wreathed in urban myths, loaded with quasi-religious significance – a boy called Yuda (Japanese for “Judas”), supposedly murdered by his own classmates, and said to have “four wives”.

Moving to a new town and a new school, sparky teenager Tetsuko Arisugawa (“Alice”) is still getting used to her new surname after her parents’ divorce. Dad is a charmer but a loser in life; Mum is a flaky author with a habit of dramatising their private life for profit. Meanwhile, her new schoolmates claim to be sinister occultists, and a dusty, empty desk in the middle of the classroom alludes to a disaster that none dares speak of. All that she can glean is wreathed in urban myths, loaded with quasi-religious significance – a boy called Yuda (Japanese for “Judas”), supposedly murdered by his own classmates, and said to have “four wives”.

The Case of Hana & Alice is loaded with paths not taken, racking up anime stereotypes that can and have taken many other stories in sensational directions. The mysterious transfer student; the ominous empty desk; the whispering classmates; the twitching curtains across the street; the hunky unattached teacher; the colleague he might be seeing in secret; the over-tended flower garden; the vulpine class princess with occult leanings; the childhood friend who comes back into one’s life… the storyline is veritably groaning under the weight of schlocky set-ups, none of which turns out to go anywhere. It’s not that Alice has inherited her mother’s over-active imagination, so much that her mother remains happily ensconced in a wistful teenage daydream, where every word and deed has the potential to escalate into world-shattering drama. It’s this stage of teenagerdom that The Case of Hana & Alice relishes, not the tall tales that its characters concoct. Its storyline takes anime tropes in reverse, winding back into real-life inspirations and everyday misunderstandings.

In the character of Hana, truant and shut-in, Alice finds the perfect friend and the perfect foil. Ridiculously likeable and believably inept, the pair blunder into a series of spiralling situations, until a simple search for information has generated a bunch of new urban myths of its own. They cut a swathe through suburban Japan, leaving chaos and bafflement in their wake in a film that lovingly celebrates the silliness of kidulthood.

In the character of Hana, truant and shut-in, Alice finds the perfect friend and the perfect foil. Ridiculously likeable and believably inept, the pair blunder into a series of spiralling situations, until a simple search for information has generated a bunch of new urban myths of its own. They cut a swathe through suburban Japan, leaving chaos and bafflement in their wake in a film that lovingly celebrates the silliness of kidulthood.

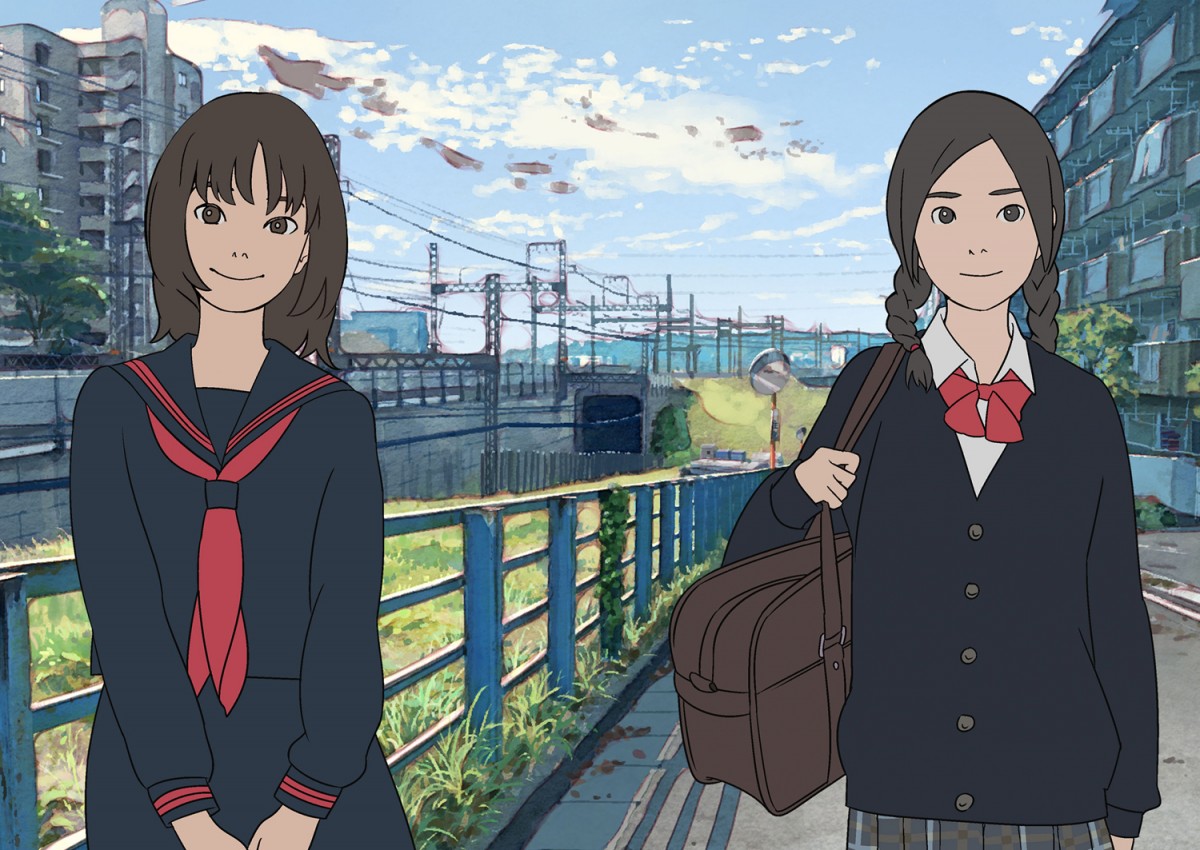

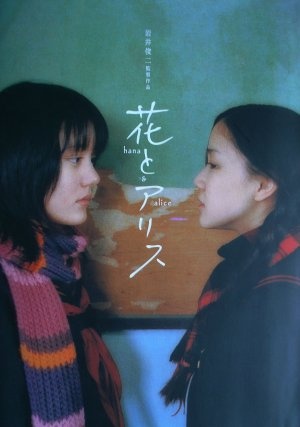

Its original inspiration, the earlier live-action movie Hana & Alice (2004), was a quirky, sardonic riff on While You Were Sleeping, in which two deluded school friends convince an amnesiac boy that one of them is his girlfriend, and the other his embittered, stalking ex. The film began as a series of commercials for Kit-Kat – Nestlé remains a sponsor, and can be held responsible for a laughably blatant moment of product placement in the follow-up. But the original made stars of its then-teenage leads Yu Aoi and Anne Suzuki, and was a jewel in the crown of director Shunji Iwai’s turn-of-the-century output. The Case of Hana & Alice (2015), is a prequel, outlining the girls’ first meeting in their mid-teens, and billing itself, in imitation of their own playful self-regard, as a murder mystery. Since both actresses are now over a decade older, their teenage selves are cunningly recreated by the use of adding their voices to rotoscoped footage – shot live and then over-drawn to give it the appearance of anime. Single stills look like any other Japanese cartoon, but when the pictures actually come to life, they display a fluidity of motion that only the most expensive of animation budgets can ever aspire to.

Its original inspiration, the earlier live-action movie Hana & Alice (2004), was a quirky, sardonic riff on While You Were Sleeping, in which two deluded school friends convince an amnesiac boy that one of them is his girlfriend, and the other his embittered, stalking ex. The film began as a series of commercials for Kit-Kat – Nestlé remains a sponsor, and can be held responsible for a laughably blatant moment of product placement in the follow-up. But the original made stars of its then-teenage leads Yu Aoi and Anne Suzuki, and was a jewel in the crown of director Shunji Iwai’s turn-of-the-century output. The Case of Hana & Alice (2015), is a prequel, outlining the girls’ first meeting in their mid-teens, and billing itself, in imitation of their own playful self-regard, as a murder mystery. Since both actresses are now over a decade older, their teenage selves are cunningly recreated by the use of adding their voices to rotoscoped footage – shot live and then over-drawn to give it the appearance of anime. Single stills look like any other Japanese cartoon, but when the pictures actually come to life, they display a fluidity of motion that only the most expensive of animation budgets can ever aspire to.

This can be a difficult sell for both live-action and animated audiences. The film was in competition at 2015’s Scotland Loves Anime festival, where the jury hotly debated whether it was reasonable to confer an award on an animated film that was not “really” animated. Even though it was pipped at the post by Miss Hokusai for the coveted Golden Partridge, it was a clear winner in the voting for the rival Audience Award. But Hana & Alice is part of a long tradition in cartooning, stretching back to Disney’s Snow White & the Seven Dwarfs, which was similarly shot as-live and then augmented with extras. Like Snow White, Hana & Alice betrays its origins not only with perfect motion – particularly in dance sequences that reference and evoke similar moments in the 2004 original – but also with faces that can drift off-model: one of the perils of realism being an absence of the impressionistic guidelines that allow animators to impart symbolic emotion to animated faces.

This can be a difficult sell for both live-action and animated audiences. The film was in competition at 2015’s Scotland Loves Anime festival, where the jury hotly debated whether it was reasonable to confer an award on an animated film that was not “really” animated. Even though it was pipped at the post by Miss Hokusai for the coveted Golden Partridge, it was a clear winner in the voting for the rival Audience Award. But Hana & Alice is part of a long tradition in cartooning, stretching back to Disney’s Snow White & the Seven Dwarfs, which was similarly shot as-live and then augmented with extras. Like Snow White, Hana & Alice betrays its origins not only with perfect motion – particularly in dance sequences that reference and evoke similar moments in the 2004 original – but also with faces that can drift off-model: one of the perils of realism being an absence of the impressionistic guidelines that allow animators to impart symbolic emotion to animated faces.

“I had no idea how I should proceed,” Iwai said at a press conference for the Japanese release, in conversation with Makoto Shinkai. “The more I did, the more troubles it created further along, with things I should have done differently. We didn’t even agree on the way we should consistently title all the separate files, so that gradually failed. There were so many accidents like data reverting to two generations before its most recent back-up, which gave the staff so much grief.”

“The last couple of weeks were chaos. Nobody could sleep. If there was a mistake, the whole studio became silent. The atmosphere was like: ‘Whose fault is this? Maybe it was him!’… There was a horrible feeling of being cornered. Just as the footage was all coming together, a couple of days before [delivery], I found out there would be no time to adjust it. I felt total despair.”

Iwai finished the production sure that he had learned so much that he would be able to do better by his staff in future. “Based on that, I thought that I would be able to be more humane next time. But when I said that to Hideaki Anno, he replied: ‘That never happens in anime!’”

Hana & Alice is an intriguing product of modern Japanese film-making. Its hybrid status between live and cartoon is also likely to be a product of budgetary restrictions, affording Iwai the chance to shoot a rapid, guerrilla movie, knowing that issues in lighting, sound, or backgrounds can be fixed in post-production. Watch out for Alice’s disappearing coat near the swings in the park, a continuity error that lingers as evidence of a break-neck schedule, and periodic shadows that suggest the whole thing was shot on the run. Just as the production of Perfect Blue was downgraded from a live B-movie to an A-grade anime, Hana & Alice uses its animation staff as the ultimate in fixers, salvaging a workable print from a movie that might have otherwise been unfit for purpose.

“In live-action film-making, you to have to give up so much more than in anime,” enthused Iwai. “On live productions, I have these images in my mind before production begins, but I have to jettison them because there are always restriction on quality. In anime, you often find yourself saying ‘That was too simple, let’s try this!’ My next film is going to be live-action, but I definitely want to work with animation again.”

The Japan of The Case of Hana & Alice is not a sinister metropolis of muggers and rapists, but an entirely benevolent society of kindly passers-by and chivalrous strangers. Buried beneath the comedy situations of Iwai’s script is a study in what the Japanese call omotenashi, an ingrained kindness for the sake of kindness, with no expectation of reward. Just like the idealised 1950s countryside of My Neighbour Totoro, which Alice briefly acknowledges in an aside, the film’s world is one without danger or confrontation, where even a pair of clueless runaway teenagers can expect to be watched over by a succession of real-world angels.

The film is also part of a multimedia mix, adapted into both a manga version by Dowman Sayman and a novelisation from Otsuichi, while the onscreen imagery is evocative of a time that is already a generation in our past. The girls coordinate their activities on cell phones, with the sort of conspiratorial glee once reserved for crime-busting CB-radio fanatics in 1980s kids’ films. But those same devices are now also gateways to entire worlds of data. The Case of Hana & Alice is a period piece, like several other modern Japanese dramas, because the super-connected digital generation of 2015 would have been able to solve all of its problems and mysteries in 30 seconds with Google and Facebook.

The film is also part of a multimedia mix, adapted into both a manga version by Dowman Sayman and a novelisation from Otsuichi, while the onscreen imagery is evocative of a time that is already a generation in our past. The girls coordinate their activities on cell phones, with the sort of conspiratorial glee once reserved for crime-busting CB-radio fanatics in 1980s kids’ films. But those same devices are now also gateways to entire worlds of data. The Case of Hana & Alice is a period piece, like several other modern Japanese dramas, because the super-connected digital generation of 2015 would have been able to solve all of its problems and mysteries in 30 seconds with Google and Facebook.

One wonders if kids today have as much of a chance to be charmingly silly – sharing memes on Twitter is hardly the same thing. But after the film’s UK premiere, I was waiting outside the cinema as a 12-year-old girl came out. She was humming the film’s closing theme and began to skip, happily down the street.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History.

The Case of Hana & Alice is released in the UK by Anime Limited.

anime, film, Hana & Alice, Hana and Alice, Japan, Japan Foundation, Jonathan Clements, live-action, rotoscoping, Shunji Iwai, The Case of Hana & Alice

Leave a Reply