Warning! Chatterley

July 12, 2016 · 0 comments

Jonathan Clements reviews a book on Japan’s landmark censorship cases.

It began with newsboys in the Tokyo streets with stacks of a racy foreign book, wearing jackets that proclaimed “WARNING! CHATTERLEY.” For the first big test of Japan’s new free-speech constitution was the publication of the unexpurgated Lady Chatterley’s Lover in 1951, when the country was still under the American Occupation. Japanese censors had originally hoped to nobble Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead, but it had a pacifist message that chimed well with the Americans. Instead, they went for DH Lawrence’s book, in part because of its naughty language and the suggestion it might be corrupting, but also for its depiction of Lord Chatterley, an impotent war hero liable to ruffle feathers among Japan’s defeated veterans.

It began with newsboys in the Tokyo streets with stacks of a racy foreign book, wearing jackets that proclaimed “WARNING! CHATTERLEY.” For the first big test of Japan’s new free-speech constitution was the publication of the unexpurgated Lady Chatterley’s Lover in 1951, when the country was still under the American Occupation. Japanese censors had originally hoped to nobble Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead, but it had a pacifist message that chimed well with the Americans. Instead, they went for DH Lawrence’s book, in part because of its naughty language and the suggestion it might be corrupting, but also for its depiction of Lord Chatterley, an impotent war hero liable to ruffle feathers among Japan’s defeated veterans.

As recounted in Kirsten Cather’s book, The Art of Censorship in Postwar Japan, the Chatterley case soon assumed absurd proportions – if you put it in a novel, nobody would believe it. One psychologist tried to argue a statistical case for corruption, by counting the number of orgasms. Another wired witnesses to a lie detector and read them pornography, trying to show a correlation of arousal in response to paragraphs from the book. Some of the arguments rested on the words themselves, with translator Sei Ito offering fascinating testimony about his decisions to be blunt and direct, and not to make any of the localising euphemisms often employed in translations of foreign books into Japanese. There is plenty of food for thought here for the Japanese linguist, as lawyers debate the best way to translate rude words – as direct Japanese, as medical terminology, as poetic imagery (a “chrysanthemum seat”, apparently, is an anus) or as direct transliteration of the English terms, which would be unintelligible to the average Japanese reader, and frankly wouldn’t be a “translation” at all.

Cather’s book tracks censorship in Japan from the landmark Chatterley case, through several key cinema and literary rulings, all the way to the present day and the first manga to have its merits debated in court. Her wit and irreverence takes its cue from VS Naipaul, who quipped on the issuing of a fatwa against Salman Rushdie that the Ayatollah of Iran was offering a somewhat extreme form of literary criticism. She moves into film in the 1960s, revealing that Tetsuzo Watanabe, last seen in Anime: A History leading a group of tanks against striking special effects technicians at Toho, went on to find an even more bonkers job working for the censorship authority Eirin. Eirin saw themselves as defenders of public morals, surrounded by an ever-rising tide as erotica as Japanese cinemas increasingly chased the blue-movie market. The statistics do not lie; Cather uses metadata to point to the transformation of Japanese cinema. “In 1963, only 37 of the 370 films checked by Eirin warranted adult ratings, whereas by 1965 the number had reached 233 of the total 503.”

Cather’s book tracks censorship in Japan from the landmark Chatterley case, through several key cinema and literary rulings, all the way to the present day and the first manga to have its merits debated in court. Her wit and irreverence takes its cue from VS Naipaul, who quipped on the issuing of a fatwa against Salman Rushdie that the Ayatollah of Iran was offering a somewhat extreme form of literary criticism. She moves into film in the 1960s, revealing that Tetsuzo Watanabe, last seen in Anime: A History leading a group of tanks against striking special effects technicians at Toho, went on to find an even more bonkers job working for the censorship authority Eirin. Eirin saw themselves as defenders of public morals, surrounded by an ever-rising tide as erotica as Japanese cinemas increasingly chased the blue-movie market. The statistics do not lie; Cather uses metadata to point to the transformation of Japanese cinema. “In 1963, only 37 of the 370 films checked by Eirin warranted adult ratings, whereas by 1965 the number had reached 233 of the total 503.”

It’s enthralling to read Cather’s account of the arguments over Black Snow, an eroticised frippery that contained sharp, indictments of the corrupting influence of American culture in the Occupation era. Japanese prostitutes are depicted mastering pidgin English, but only learning about their own culture in order to have something to say when their GI boyfriend asks them about kabuki. The prosecution argues that this is all a political smokescreen to justify shots of jiggly bosums. The defence argues that the jiggly bosums conceal a political message.

And so it goes on with the Japanese court room turned into an impromptu forum for a discussion of art and entertainment in a free society – witness the moment when an incredulous witness in the dock asks his prosecutor why the authorities think adult audiences can be trusted not to imitate images of murder, but need to be protected from the sight of sexual intercourse. Naturally, Cather devotes plenty of space to In The Realm of the Senses, the erotic film whose director, Nagisa Oshima, was so sure of getting into trouble that he didn’t even develop it in Japan, preferring to do so in France. But he was caught anyway when he published the script in Japan, and included some photographs that were too hot for the prosecutors.

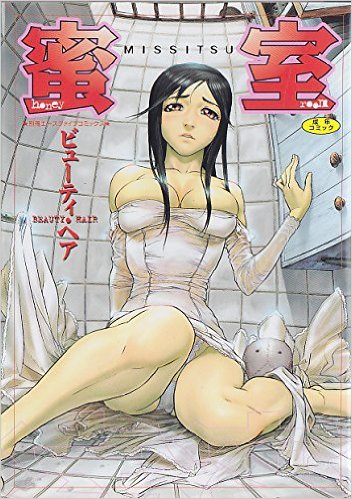

But it’s the last series of cases that are the most intriguing, as Cather chronicles the troubled court battles this century over Honey Room, an erotic manga by the artist “Beauty Hair” in which, in Cather’s words, “both sides adopted the mantle of feminism” – the prosecutors complaining about the abuse and subjugation of women in the comic, while the defence produced Yukari Fujimoto, an anti-censorship critic who was prepared to argue that scenes in the manga depicted “mutually pleasurable sex”, suggesting that even supposed rape victims were actually role-playing.

But it’s the last series of cases that are the most intriguing, as Cather chronicles the troubled court battles this century over Honey Room, an erotic manga by the artist “Beauty Hair” in which, in Cather’s words, “both sides adopted the mantle of feminism” – the prosecutors complaining about the abuse and subjugation of women in the comic, while the defence produced Yukari Fujimoto, an anti-censorship critic who was prepared to argue that scenes in the manga depicted “mutually pleasurable sex”, suggesting that even supposed rape victims were actually role-playing.

Wherever you stand on censorship, the case makes for fascinating reading, as Cather dissects the strategies of both defence and prosecution, and the rhetoric of manga apologists. She outlines what she calls the “insecure pretension” of defenders of comics who use high-faluting terms like “graphic novel”, or who attempt to relate modern pictorial media to old-time antecedents like Hokusai. But she also notes the intriguing parallels and double-standards of the authorities, who turn a blind eye to the publication of explicit art books by the print artist Utamaro, but complain about a bit of boob in an adult comic. Shunga – erotic prints – are dragged into the argument in a most entertaining fashion, after the prosecution suggests that Honey Room is nothing but grunts and groans. A classical scholar is produced to read some of the squiggles in the back of the average “classy” Edo-period erotica, which turn out to be nothing but grunts and groans as well.

Author Tamaki Saito also shows up for the defence, mounting a deeply suspect argument that otaku are “unable to act on their sexual desires”, which is what makes them otaku in the first place. Anyone who has had sex at an anime convention should hand back their fan badge, it seems. Saito was, of course, disingenuously conflating otaku with hikikomori, but he also tripped himself up with his claims that there was no chance whatsoever of real-life harm. As Cather points out herself, what about Tsutomu Miyazaki, the infamous otaku murderer, who was arrested after he murdered four young girls?

There’s also some remarkably interesting data about the distribution of adult comics in Japan – the notorious Honey Room is sold via a surprisingly small number of bookstores (just 35), but is reprinted a surprising number of times, clocking up three iterations in just two years before a “concerned parent” found a copy in his son’s bedroom and reported the publisher to the police. For publishing nerds like me, the most exciting elements are too be found in the logistics of bagging – no, not a bizarre sexual practice, but the mundane concept of protecting casual browsers by sealing adult comics in plastic bags. Introduced by Honey Room’s publisher in 1989, the idea costs them between two and five yen a time, racking up additional costs on the average print run of up to £1000, all so people can’t see your product!

Anyone with an interest, pro- or anti-, in Japanese erotica will find plenty of food for thought in Cather’s book, as she debates whether pornography is a “safety valve or boiler room”, and whether art should be “mimetic or deformative”. She ends with a telling comment about the rise of the internet, which she suggests has rendered “quixotic” much of the task of the censor, in a world where such images can be piped directly to someone’s phone or laptop.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History. Kirsten Cather’s The Art of Censorship in Postwar Japan is published by the University of Hawaii Press.

anime, Beauty Hair, books, censorship, erotica, hentai, Honey Room, Japan, Jonathan Clements, manga, Misshitsu, Missitsu, Realm of the Senses

Leave a Reply