Yellow Submarine

July 6, 2018 · 0 comments

by Jeremy Clarke.

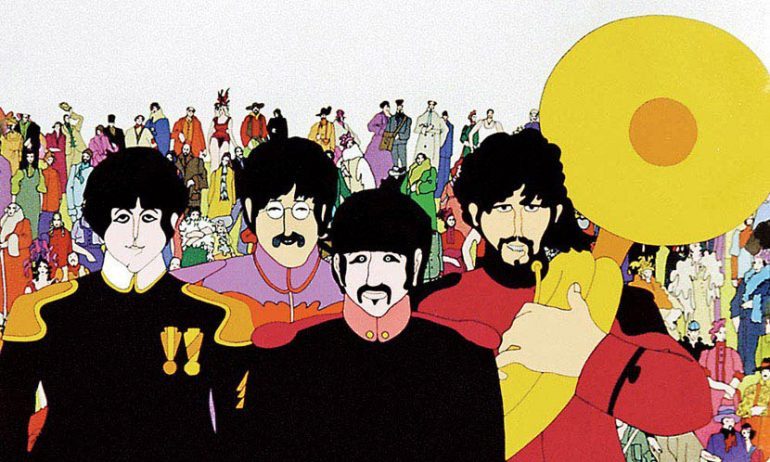

Back on the big screen in a welcome one-day outing fifty years after its original 1968 release, The Beatles: Yellow Submarine remains one of the most remarkable animated feature films ever made. It turned the medium on its head in the English-speaking world, eschewing Disney’s dominant visual style and children’s audience for something much more experimental, aimed at older viewers.

Back on the big screen in a welcome one-day outing fifty years after its original 1968 release, The Beatles: Yellow Submarine remains one of the most remarkable animated feature films ever made. It turned the medium on its head in the English-speaking world, eschewing Disney’s dominant visual style and children’s audience for something much more experimental, aimed at older viewers.

The Beatles themselves were emblematic of the decade. John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr morphed from suited and booted mop-top heartthrobs who sang Please Please Me to screaming teenage girls into colourfully clad, long-haired spokesmen for a generation. Their seminal Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album provided the inspiration for the film.

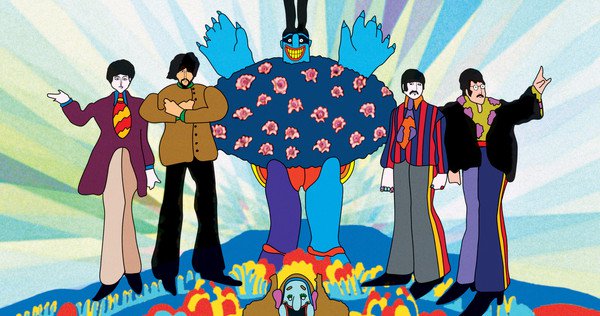

Yellow Submarine is loosely woven around a number of Beatles songs, 12 in all, four of them new, another four from the Sergeant Pepper album and one a hit song providing the title. The script follows a basic quest structure. Pepperland is a place of colour, love and harmony where the people relax in the park to Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The army of the Blue Meanies attacks Pepperland, intent on destroying all music and reducing colour to a monotone more to the Meanies’ dull taste. As Pepperland’s defeat seems certain, its Lord Mayor sends Young Fred away in a yellow submarine to get help. He enlists the Beatles. Together, they travel through several seas – the Sea of Time, the Sea of Monsters, the Sea of Holes and, from the title song, the Sea of Green – to Pepperland where, posing as Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, the Beatles use the power of music to overcome the Blue Meanies and restore the country to its former pleasant and colourful state.

Thanks to a bad TV contract signed by manager Brian Epstein, there was already a Beatles cartoon TV series in the US which exploited their music successfully but reduced John, Paul, George and Ringo to unrepresentative, stock characters. The band disliked it intensely and wanted nothing to do with any proposed animated feature. Co-founder of London’s TVC (Television Cartoons) studio John Coates had similar misgivings, having done the animation on the series. But exposure to recordings from the soon-to-be-released Sergeant Pepper album convinced him that the feature was something with which his studio needed to be involved.

Thanks to a bad TV contract signed by manager Brian Epstein, there was already a Beatles cartoon TV series in the US which exploited their music successfully but reduced John, Paul, George and Ringo to unrepresentative, stock characters. The band disliked it intensely and wanted nothing to do with any proposed animated feature. Co-founder of London’s TVC (Television Cartoons) studio John Coates had similar misgivings, having done the animation on the series. But exposure to recordings from the soon-to-be-released Sergeant Pepper album convinced him that the feature was something with which his studio needed to be involved.

When a script by Harvard and Yale classics scholar Erich Segal failed to grasp the intricacies of Liverpudlian dialogue, it fell to uncredited Scouse poet Roger McGough to rewrite it and effectively recreate the Fab Four’s natural camaraderie so evident in their televised press conferences. Woven brilliantly into the dialogue are numerous Beatles lyrics and title references.

Actors John Clive, Geoff Hughes and an uncredited Peter Batten voice John, Paul and George respectively. Paul Angelis takes on Ringo plus the additional roles of the head Meanie and the narrator. Lance Percival, who had voiced Paul and Ringo for the TV series plays Young Fred, which character frequently refers to himself as Old Fred. Dick Emery has the multiple roles of the Lord Mayor, the Blue Meanie sidekick Max and the Nowhere Man Jeremy Hillary Boob PhD.

Helming the production was director George Dunning, a Canadian who’d worked with animation pioneer Norman McLaren in the fifties before founding TVC in London with the more business-oriented Coates in 1957. Dunning and Coates hired Czech-German designer Heinz Edelmann to give the feature a unique look, radically different from anything previously seen in animated movies and arguably since.

Unlike the slick animation techniques of Disney, then the industry standard with their rounded figures of light and shade, naturalistic character movement and squash-and-stretch dynamic, Edelmann’s visuals often showed characters facing camera or in profile at ninety degrees to it. Flat areas of colour are very much to the fore with a palette not dissimilar to the foursome’s photos on the Sergeant Pepper LP cover.

The real life Beatles were so impressed with the direction the film was taking on a mid-production visit to TVC that they shot a live-action epilogue and contributed the recordings of the four new songs.

Specific sections stand out. The early Eleanor Rigby sequence which does little more in narrative terms than introduce the urban environment of Liverpool as Young Fred’s submarine searches for the Beatles is a masterpiece of cinematic photo-collage, employing newsreel footage, cut-outs and photographs. The later Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds sequence uses rotoscoping, the technique of tracing images from live action frame-by-frame, in a way that had never been done before. Rather than copying footage of live-action figures to produce a hyper-realistic animated character as Max Fleischer did in Gulliver’s Travels (1939), Dunning takes the drawings from footage of a girl dancing as a springboard for his artists to go completely wild with paint, which differs utterly in composition from one frame to the next, leading to some truly arresting moving images. And When I’m 64 includes a memorable minute, counted off one second at a time.

Specific sections stand out. The early Eleanor Rigby sequence which does little more in narrative terms than introduce the urban environment of Liverpool as Young Fred’s submarine searches for the Beatles is a masterpiece of cinematic photo-collage, employing newsreel footage, cut-outs and photographs. The later Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds sequence uses rotoscoping, the technique of tracing images from live action frame-by-frame, in a way that had never been done before. Rather than copying footage of live-action figures to produce a hyper-realistic animated character as Max Fleischer did in Gulliver’s Travels (1939), Dunning takes the drawings from footage of a girl dancing as a springboard for his artists to go completely wild with paint, which differs utterly in composition from one frame to the next, leading to some truly arresting moving images. And When I’m 64 includes a memorable minute, counted off one second at a time.

Other impressive elements include two particularly nightmarish characters in the Blue Meanie army. One is the Apple Bonkers, monstrously tall, thin men wearing top hats who drop giant apples from a great height onto unsuspecting victims, petrifying them on impact. Worse still, the Flying Glove is the subject of the chief Meanie’s soothing, caressing words who then hunts down and viciously squashes those he pursues with more than a hint of vindictiveness. It’s hard to think of a more frightening apparition in any film ever, animated or otherwise.

The Beatles: Yellow Submarine is back on the big screen in the UK and Ireland on Sunday 8th July 2018.

Leave a Reply