Chie the Brat

September 26, 2017 · 0 comments

Jonathan Clements on Isao Takahata’s obscure pre-Ghibli comedy.

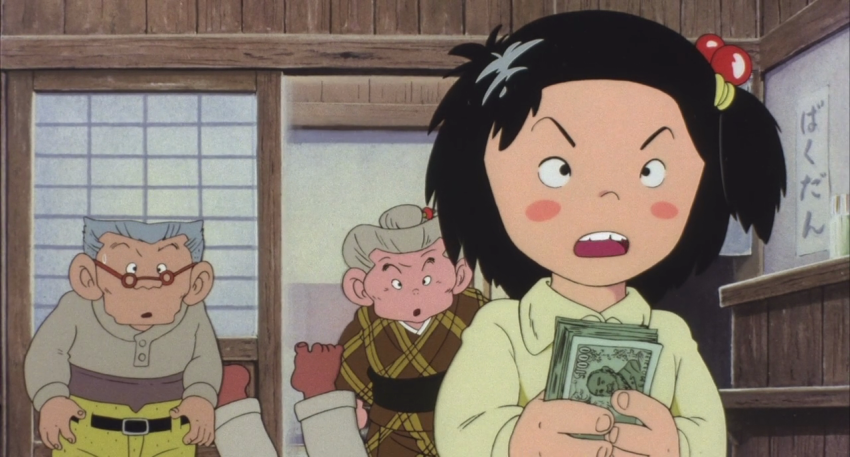

Chie the Brat, the adventures of “the unluckiest girl in Japan,” was conceived as a slapstick celebration of blue-collar life in Osaka, based on an award-winning strip by Etsumi Haruki in Manga Action. Chie helps out at the family restaurant, a shack selling grilled offal in downtown Osaka. Her father Tetsu is irascible and violent, not always comically so, while local rake Occhan is a gangster turned okonomiyaki seller. Chie’s relentlessly good-natured mother, as well as Kotetsu and Antonio, a pair of fighting cats, round off the cast. “No other comic has depicted Osaka people in this way,” wrote animator Yasuo Otsuka in his memoirs, “loveable and living without pretension, despite not being cool. The subjects of mainstream animation in Japan are superhumans, legendary heroes and fantasies, so Chie the Brat, with its life-sized humans and a funny cat, was very much a pole apart.” Today, it remains an obscure but intriguing entry on the CV of future Ghibli star director Isao Takahata.

Chie the Brat, the adventures of “the unluckiest girl in Japan,” was conceived as a slapstick celebration of blue-collar life in Osaka, based on an award-winning strip by Etsumi Haruki in Manga Action. Chie helps out at the family restaurant, a shack selling grilled offal in downtown Osaka. Her father Tetsu is irascible and violent, not always comically so, while local rake Occhan is a gangster turned okonomiyaki seller. Chie’s relentlessly good-natured mother, as well as Kotetsu and Antonio, a pair of fighting cats, round off the cast. “No other comic has depicted Osaka people in this way,” wrote animator Yasuo Otsuka in his memoirs, “loveable and living without pretension, despite not being cool. The subjects of mainstream animation in Japan are superhumans, legendary heroes and fantasies, so Chie the Brat, with its life-sized humans and a funny cat, was very much a pole apart.” Today, it remains an obscure but intriguing entry on the CV of future Ghibli star director Isao Takahata.

Propelled suddenly into both a feature anime and an anime TV series in 1981, Takahata was lured into the production by his colleague Yasuo Otsuka when he was supposed to be enjoying a post-production holiday after finishing Anne of Green Gables. “The producer told me to ask Paku-san,” remembers Otsuka, using the affectionate nickname for Takahata, based on his habit of grazing on pieces of toast around the studio [paku-paku is “munch-munch”, hence also Pacman]. Takahata refused to get involved until he had checked out the comic original himself, but came back ready and enthusiastic to take the job.

Animator Yoichi Kotabe recalled reading the Chie manga at a café – a phrasing that suggests he never shelled out for a copy, but was happy to flip through the freebies lying around noodle bars. For him, the anime would be the first time he had worked with Takahata and Otsuka since Panda Go Panda nearly a decade earlier, representing the slow accretion of the team that would eventually make Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind in years to come. “Me, Paku-san and Otsuka-san all agreed that we should respect Haruki Etsumi’s original thoroughly,” he told anime historian Seiji Kano. “We tried to make the most of the robust, expressive taste of the original. Otsuka did Tetsu most of the time, and I drew Chie and Kotetsu the cat. By getting into the role, animators could get twice as much enjoyment out of drawing pictures with different flavours.”

“The protagonists are all morons,” observed Otsuka, using the Osaka dialect term aho. “But they have these great relationships, like Occhan the okonomiyaki seller, whose relationship with his cat Antonio changes when he is drunk, and Tetsu, who fails to be a match for his well-mannered wife. And more than anyone else, Chie, who has to balance her full school life with helping at the restaurant. But Paku-san’s direction makes the audience think of all of these characters as loveable people. There’s no pretense, and the camerawork makes the viewers feel they are among the characters. There is a true respect for the point of view of the original, even down to the aggressive old lady and the stupidity of the small-time yakuza.”

“The protagonists are all morons,” observed Otsuka, using the Osaka dialect term aho. “But they have these great relationships, like Occhan the okonomiyaki seller, whose relationship with his cat Antonio changes when he is drunk, and Tetsu, who fails to be a match for his well-mannered wife. And more than anyone else, Chie, who has to balance her full school life with helping at the restaurant. But Paku-san’s direction makes the audience think of all of these characters as loveable people. There’s no pretense, and the camerawork makes the viewers feel they are among the characters. There is a true respect for the point of view of the original, even down to the aggressive old lady and the stupidity of the small-time yakuza.”

Norio Nishikawa, who played Chie’s father Tetsu in both movie and television versions, was a celebrity stand-up at the time and something of a catch. However, his edgy humour, often improvised in the recording booth, would cause headaches for television producers, when he dared to throw in “Baka da-nee” as a punchline so regularly that it turned into a catchphrase. In English, it sounds ridiculously tame: “That’s so stupid” or “You’re so stupid”, but in a language where even long-term friends add honorifics to each other’s names, it sounds callous and contemptuous.

A board member from the TV broadcaster came over to Tokyo Movie to protest about the use of inappropriate language, only for Takahata to turn on him, shouting that they should have thought of that before they bought the rights to a series about Osaka slum life.

“Because both the film version and the TV version were being made around the same time,” remembered script supervisor Keishi Yamazaki, “the producer figured they were both based on the same original, so we could just recycle clips from the film on television. It must have seemed natural to him, to save money and time. However, this cost-cutting measure backfired. Inserting animation created for a film into the middle of a TV show would look strangely high-quality, so the whole work would become unbalanced.”

The animators, however, came up with an off-the-wall solution, upgrading the entire TV series to movie quality, using two to three times as many cels per episode as were usually required for TV.

Sometime after the film was created, the producer Yutaka Fujioka had subtitles made up for it to show to Disney stalwarts Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston. “They were really amazed,” recalled Otsuka, “and said it was the best Japanese animation that they had seen to that date. There were, they observed, many ‘Tetsus’ in the United States as well, but Chie reminded them of strong, admirable children in America. The kind of warm perspective and solid human depictions were something Disney hadn’t [yet] achieved. [They said:] ‘People will certainly understand this work one day. It is a wonderful work, and we applaud you from the bottom of our hearts.’”

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History.

anime, Chie the Brat, Isao Takahata, Japan, Jonathan Clements, Scotland Loves Anime, Yasuo Otsuka, Yoichi Kotabe

Leave a Reply