Satoshi Kon: Seraphim and Opus

October 19, 2015 · 0 comments

By Raz Greenberg.

It’s been five years since the shocking news of Satoshi Kon’s death, and the animation world is still mourning. The news that there’s nothing more coming from one of the man who directed innovative works as Perfect Blue and in his short lifetime managed to influence significant works by leading directors as Darren Aronofsky and Christopher Nolan was indeed shocking. But for the non-Japanese audience there was still a whole body of Kon’s works waiting to be discovered beyond his anime filmography: his early works as a manga artist. English-speaking readers got their first taste of Kon’s manga with vertical’s collected edition of his short series Tropic of the Sea, a mythological tale set in a modern Japanese beach resort which featured beautiful artwork but also a rather uninspired story.

It’s been five years since the shocking news of Satoshi Kon’s death, and the animation world is still mourning. The news that there’s nothing more coming from one of the man who directed innovative works as Perfect Blue and in his short lifetime managed to influence significant works by leading directors as Darren Aronofsky and Christopher Nolan was indeed shocking. But for the non-Japanese audience there was still a whole body of Kon’s works waiting to be discovered beyond his anime filmography: his early works as a manga artist. English-speaking readers got their first taste of Kon’s manga with vertical’s collected edition of his short series Tropic of the Sea, a mythological tale set in a modern Japanese beach resort which featured beautiful artwork but also a rather uninspired story.

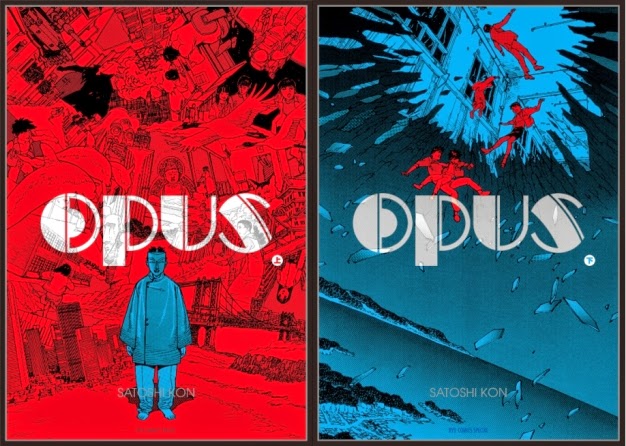

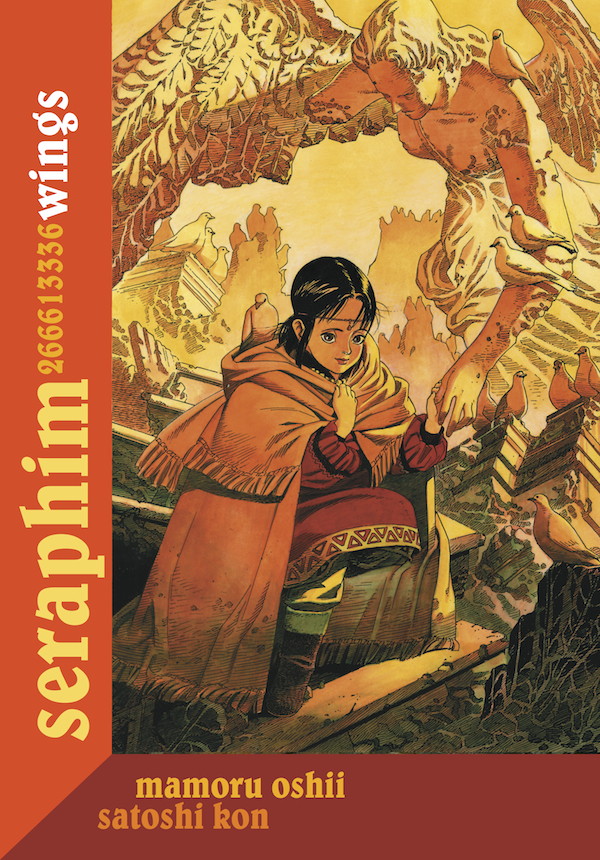

Now come two other collected volumes of Kon’s adventures in manga, published by Dark Horse: Seraphim 26661336 Wing and Opus. Seraphim is the more high-profile work of the two, drawn by Kon and written by another famous anime director whose influence extended beyond Japan, Mamoru Oshii. The series’ original Japanese publisher, Animage magazine, clearly had high aspirations for it given that it was chosen to fill the very big shoes of Hayao Miyazaki’s Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind upon the latter’s conclusion in 1994. Late 20th-century anime fans have every reason to be excited about the series as well – the director of Perfect Blue and the director of Ghost in the Shell doing a joint manga project! How could this possibly go wrong?

In more ways than you can imagine, it turns out, as Seraphim is a beautiful but incoherent, and boring mess. Set against the backdrop of a terrible plague that turns its victims into deformed, winged corpses, the plot follows a team assigned to the case of the plague centered around a mysterious girl named Sera. And just what is it that the members of this team are supposed to do? Good question. They move around a lot from one place to another; they occasionally get into hairy situations involving firearms, but they rarely, if ever, give readers any idea about what they’re hoping to achieve. The enigmatic dialogue in Seraphim certainly gives the impression of grand, important things that go on – problem is, they never seem to go on in the pages you’re currently reading. Oshii and Kon never got around to finishing the series, but by the time readers will reach the concluding chapters, they’ll have little reason to care.

Against the weakness of Oshii’s story, Kon’s artwork actually shines. From the visualization of Oshii’s usual obsessions with basset hounds and Christian imagery to ravaged urban landscapes and military hardware, Kon drew the series with impressive attention to detail. The series’ bursts of violence are also well-drawn, reminding readers of another famous manga artist turned anime director – Kon’s mentor, Katsuhiro Otomo. Kon’s fans wouldn’t want to miss the opportunity of reading Seraphim, if only for the chance to see his drawings of landscapes and objects that were largely absent of his film and television works. Coupled with a lengthy but informative afterward by Carl Gustav Horn, Seraphim makes a good purchase for artistic or historical reasons – just don’t expect anything that resembles an interesting story.

Against the weakness of Oshii’s story, Kon’s artwork actually shines. From the visualization of Oshii’s usual obsessions with basset hounds and Christian imagery to ravaged urban landscapes and military hardware, Kon drew the series with impressive attention to detail. The series’ bursts of violence are also well-drawn, reminding readers of another famous manga artist turned anime director – Kon’s mentor, Katsuhiro Otomo. Kon’s fans wouldn’t want to miss the opportunity of reading Seraphim, if only for the chance to see his drawings of landscapes and objects that were largely absent of his film and television works. Coupled with a lengthy but informative afterward by Carl Gustav Horn, Seraphim makes a good purchase for artistic or historical reasons – just don’t expect anything that resembles an interesting story.

Opus, a solo manga effort from Kon, provides a much better reading experience, though it’s still likely to leave readers unsatisfied. It tells the story of Chikara Nagai, a manga artist who finds himself sucked into and trapped inside his work – the tale of a violent struggle against a dangerous cult led by a mysterious masked figure. Things get even more dangerous when different characters within the world created by Nagai begin to realize that their creator is walking among them, and try to take advantage of the situation.

Opus was written and drawn just as Kon was making his transition into directing animated features, and it shows early signs of his familiar storytelling style that breaks the barriers between fantasy and reality. There is nothing particularly sophisticated about it here – the story plays more like a glorified version of the old A-ha music video Take on Me than anything that resembles the multilayered nature of Kon’s films – but in its initial chapters, it’s entertaining enough. Passages between the real world and the world of comics are imaginative, the protagonist’s fish-out-of-water behavior is amusing, and the violence and mayhem are exciting.

Alas, as Opus progresses, it turns out that Kon may have just been a little too autobiographical in telling a story about a manga artist losing control of his work; at some point it becomes painfully clear that Kon had no idea where he was going with his story and just piled one unlikely twist on top of the other, hoping something would stick. Like Seraphim, Kon left Opus unfinished, although the collected volume issued by Dark Horse includes the un-inked sketches for an additional chapter unpublished during the series’ original run, discovered in Kon’s files after his death. This chapter, unfortunately, turns out to be a redundant and sickeningly self-indulgent affair.

Another problem is the protagonist. Tropic of the Sea suffered from having a protagonist who just hangs around doing nothing, and readers had no reason caring for. Opus takes this a step further by giving its readers a protagonist who’s an annoying jerk. This makes it very hard to generate interest in anything that happens to him, especially as his presence pushes aside far more interesting characters as though policewoman Satoko.

Again, Kon’s art is the major selling point of Opus. The backgrounds feel somewhat less detailed compared to those of Seraphim, but the art has a far more dynamic feeling to it, as both action and dialogue give the feeling that things are always on the move. Kon was clearly already into his animator-mode here. Much like Seraphim, Opus demonstrates Otomo’s great influence on Kon, particularly in the design of urban Japanese landscapes and the fearsome cult-leader.

Opus also strongly hints of what made Kon so successful in his animation career that immediately followed the manga’s publication: the abovementioned tension between reality and fantasy, the presence of a strong (yet sadly, underused) female character caught in a cycle of violence who must also deal with her own personal trauma – these elements clearly found their way to Perfect Blue. But in his debut feature, Kon just put them into a much better use. Though providing an overall better reading experience, Opus, much like Seraphim and unlike Kon’s subsequent works in animation, leaves readers with far less than they have expected.

Raz Greenberg recently received his PhD on animation as a text from the Hebrew University.

anime, books, ghost in the shell, Mamoru Oshii, manga, Opus, Perfect Blue, Satoshi Kon, Seraphim

Leave a Reply