Toonz, Toon Shaders and Studio Ghibli

April 27, 2016 · 0 comments

Jasper Sharp investigates the hype over “free” animation software.

Last month, a press release went out under the heading ‘TOONZ goes Open Source!’ The revolutionary 2-D animation software, developed for the professional market by the Rome-based company Digital Video in 1993 and originally distributed by Softimage as Creative Toonz, has now been placed freely within the reach of the independent and the amateur filmmaker, and it was a Japanese company that had put it there.

Last month, a press release went out under the heading ‘TOONZ goes Open Source!’ The revolutionary 2-D animation software, developed for the professional market by the Rome-based company Digital Video in 1993 and originally distributed by Softimage as Creative Toonz, has now been placed freely within the reach of the independent and the amateur filmmaker, and it was a Japanese company that had put it there.

That company was Dwango, a “new media” specialist and video portal provider founded in 1997 which counts the Japanese video sharing site Nico Nico Douga and the games developer Spike Chunsoft among its interests. Dwango is part of the Kadokawa Dwango holding company, established in 2014 through a merger with the Kadokawa media conglomerate. It was a match made in heaven: the Kadokawa side of “content creation” coupled with Dwango’s clout in the field of online distribution.

But it was a rather more familiar Japanese name that stole the story and caused such a stir within the animation community. Most of the news pieces that proliferated in the wake of the original announcement noted that it was the TOONZ Studio Ghibli Version that was being made available under its new name of OpenToonz.

“With one announcement, the animation software game may have changed forever” wrote Amid Amidi in a report titled ‘Toonz Software Used by Studio Ghibli and ‘Futurama’ Being Made Free and Open Source’. Other pieces circulating via social media over the following days were even more breathless. In a piece for Wired, Matt Kamen claimed that “Animators aspiring to be the next Hayao Miyazaki are now one step closer to their dreams” while Becket Muffson concluded on The Creators Project website that “We expect an uptick in high quality Totoro tribute films and animations inspired by the semi-retired animation legend while young animators are still in a position to play around and hone their styles.” The implication seemed to be that anyone with a computer could now knock out works of the quality of Princess Mononoke in their bedrooms.

But what exactly is TOONZ, and how has the software been used over the years by Ghibli? Since its international distribution deal with Disney in 1996, Ghibli has been regarded outside Japan as a force against the proliferation of completely 3D computer-generated features that have come to dominate the commercialmarket. But 3D animation and rendering techniques have regularly been used by Ghibli since the production of Princess Mononoke (1997) – the first feature to benefit from the distribution deal – to achieve complex effects that would be impossible using traditional pen-and-ink methods.

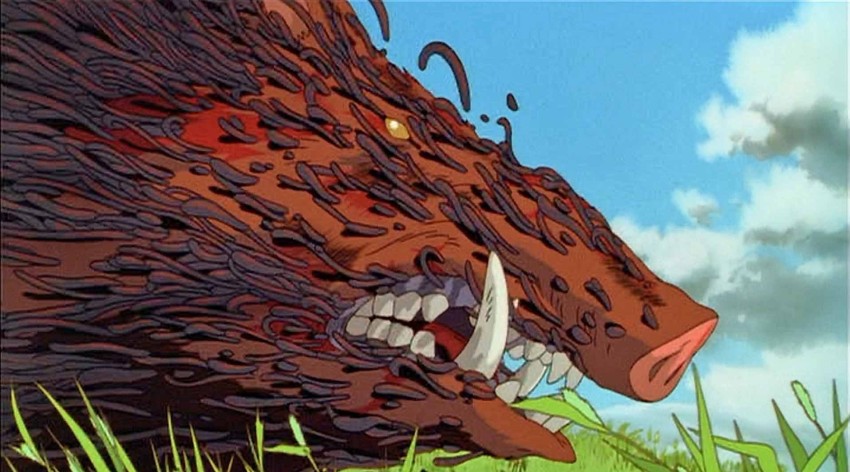

In the film’s standout scene, featuring the dynamic attack of the enraged tatarigami (a nature god incarnated as a slathering boar covered in writhing, snakelike tentacles), the boar was drawn and inked physically, but each of the individual worms covering the creature were animated as wireframe models. In Howl’s Moving Castle, to conjure up a suitable atmosphere of wartime patriotism, Miyazaki makes heavy use of flags as moving parts of the backgrounds. These again were created as 3D wireframe models, animated as if pushed by an invisible mass of air to give the impression of billowing in the wind, the relevant designs texture-mapped onto the surface, with a further degree of CG rendering to add shadows to the rumpled surfaces.

In the film’s standout scene, featuring the dynamic attack of the enraged tatarigami (a nature god incarnated as a slathering boar covered in writhing, snakelike tentacles), the boar was drawn and inked physically, but each of the individual worms covering the creature were animated as wireframe models. In Howl’s Moving Castle, to conjure up a suitable atmosphere of wartime patriotism, Miyazaki makes heavy use of flags as moving parts of the backgrounds. These again were created as 3D wireframe models, animated as if pushed by an invisible mass of air to give the impression of billowing in the wind, the relevant designs texture-mapped onto the surface, with a further degree of CG rendering to add shadows to the rumpled surfaces.

These are but two salient examples. Mitsunori Kataama, the Director of Digital Animation at Ghibli on both films, has revealed that Mononoke used 3DCG in 50 CG shots, Spirited Away had 100 shots (8% of the film), and Howl’s Moving Castle had 200 out of the 1400 shots (or roughly 15%), all of which were seamlessly blended with the hand-drawn images.

But there might be some confusion here leading to the hype from some commentators as to the influence of TOONZ on Ghibli’s characteristic style. The software responsible for the above examples was actually an entirely different entity called Toon Shaders, a collection of rendering tools used by 3D animators for simulating the “cartoon look” of traditional animation, which has nothing to do with the the TOONZ software now available Open Source.

The sole developer of Toon Shaders was Michael Arias, an American-born filmmaker currently based in Japan, best known for his production work on The Animatrix (2003) and for directing the 2005 adaptation of the Taiyo Matsumoto manga Tekkonkinkreet – both of which made heavy use of the software. Arias began work on the technology while at Softimage in 1995, refining its implementation through its first application on Princess Mononoke in close dialogue with Ghibli’s technical directors and CG animators, and then for Dreamworks’ The Prince of Egypt (1998).

Toon Shaders have regularly been employed by Ghibli in films including Spirited Away (2003) and Goro Miyazaki’s debut Tales from Earthsea (2006), as well as for countless productions by other studios both within and outside of Japan, with Arias continuing to maintain and improve it until quite recently. Shinji Aramaki’s Appleseed (2004) provides a notable instance of the renderers being used for character animation, the Toon-Shaders applied to motion-captured wireframe models to lend them the traditional cel-style anime look.

Toon Shaders have regularly been employed by Ghibli in films including Spirited Away (2003) and Goro Miyazaki’s debut Tales from Earthsea (2006), as well as for countless productions by other studios both within and outside of Japan, with Arias continuing to maintain and improve it until quite recently. Shinji Aramaki’s Appleseed (2004) provides a notable instance of the renderers being used for character animation, the Toon-Shaders applied to motion-captured wireframe models to lend them the traditional cel-style anime look.

Incidentally, subsequent to the initial patents for Toon Shaders being filed by Arias and Microsoft, and then Softimage’s owner, a number of competing vendors released software products that employed various different means to achieve a similar effect, and “Toon rendering” has become a generic term rather than explicitly referring to this original software.

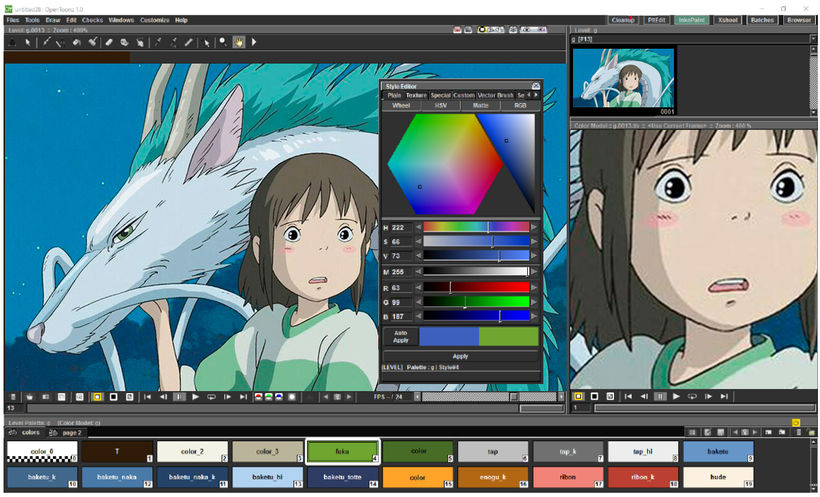

By contrast, TOONZ was developed to streamline the production process of hand-drawn animation and is much more generic in its application. Given his proximity to the production of Princess Mononoke, also the production for which this 2D package was first adopted, I asked Arias for some insight into how it was used by the studio and what we should expect from the new availability of the Studio Ghibli Version of TOONZ.

It is no great revelation to say that computers have featured prominently in the production process of commercial animation since long before the TOONZ software was first used for the production of Balto (1995) by Steven Spielberg’s Amblimation studio (it was subsequently employed on Fox Animation Studios’ Anastasia, released in 1997). Even in the most traditional-looking productions, computers play a vital role in the processes of compositing, colouring and cleaning up the hand-drawn layers of the finished images, even when the original sources are purely hand-drawn.

As Arias explains, “Nowadays all (or very nearly all) ‘traditional’ animation ends up being finished digitally — though the initial drawings may still originate on pencil and paper as they are in most Japanese anime studios, this artwork is ultimately scanned and then cleaned up (‘inked’) and coloured (‘painted’) in software.”

In the pre-digital age, pencil artwork would be transferred to acetate cels and colour would be applied by brush to the backs of these. The completed individual cels would be photographed frame-by-frame onto film using a rostrum camera.

The key strength of TOONZ, according to Arias, is that it “streamlines the path from scanning to final output, and brings with it ease of adjustment and various quality enhancements that come with a digital workflow and user interface.” The process begins with in-between pencil line drawings on punched animation paper, which are scanned using a dedicated scanning rig that lines them up according to the punch hole positions. The software then cleans up and converts these to a sequence of anti-aliased line artwork files. The final part of the process is the digital addition of colour using a palette typically specified by the colourist or art director.

In other words, rather than providing a new way of doing animation, Arias sees TOONZ and similar packages as “a digital replacement for a previously analog photo-mechanical/optical process… a modern tool, perhaps as digital sound mixing consoles are compared to old analog desks.”

The free availability of OpenToonz does offer one obvious major advantage in that previously it has been prohibitively expensive for all but the most major studios. Studio 4C, with whom Arias worked on The Animatrix, Mind Game and Tekkonkinkreet, found “there were cheaper alternatives that worked well enough for the scanning/cleanup/colouring part of the process”, although Arias acknowledges “TOONZ may well have been the best all-around solution for the task.”

The free availability of OpenToonz does offer one obvious major advantage in that previously it has been prohibitively expensive for all but the most major studios. Studio 4C, with whom Arias worked on The Animatrix, Mind Game and Tekkonkinkreet, found “there were cheaper alternatives that worked well enough for the scanning/cleanup/colouring part of the process”, although Arias acknowledges “TOONZ may well have been the best all-around solution for the task.”

As he elaborates, when Ghibli first start using digital tools and techniques the “production environment was much more homogenous than it is now”, dominated by a couple monolithic packages like Softimage 3D (and later XSI) and Alias Animator (and subsequently Maya). It was “a much simpler landscape back in the 90’s, whereas now it is a big collection of specialised software tools (now everyone uses many packages and a lot of “glue” code to go-between).”

One might therefore question the extent to which OpenToonz provides possibilities for the independent animator that weren’t there before. In this respect, it is worth zeroing in on the part of the original press release that states that while Dwango is “allowing the animators’ community to use a state of the art technology at no cost”, it will still be “offering to the industry commissioning, installation & configuration, training, support and customization services” (presumably not for free!) and will “also continue to develop and market a Toonz Premium version at a very competitive price for those companies willing to invest in the customization of Toonz for their projects.”

As to the specifics of the Studio Ghibli Version, Arias can only speculate: “I’d guess these features are customisations local to Ghibli’s pipeline, presumably a dedicated palette format and maybe some improved scanning/cleanup features.” In any measure, TOONZ has been just one of a number of software packages used by the studio, and to what extent it alone contributed to Ghibli’s developing in-house aesthetic from Mononoke onwards compared with other digital tools and packages is a moot point.

As Arias surmises, “I’d say most of the innovation at Ghibli was in interesting application of existing software plus first rate art direction. Either way, any traditional animation house relying on digital animation (2D or 3D) in those days had to have a technical director or digital animation person who evangelized the capabilities of the tool to the ‘traditional’ creative staff. Part of being a ‘traditional’ craft is a certain conservative outlook on tools and technology (as witnessed by Ghibli’s back-to-basics approach of late).”

In a nutshell, it seems the revolutionary potential of OpenToonz has been rather overstated: imagination, artistry, rich storytelling, technical expertise and perhaps most crucially a gargantuan amount of person-hours will continue to remain key factors when it comes to creating state-of-the-art animation. Ultimately these are things that will never be freely available online.

Jasper Sharp is the author of the Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema. Michael Arias will be appearing at MCM Expo in the last weekend of May.

Leave a Reply