Animerama

June 17, 2018 · 0 comments

By Jasper Sharp.

The three titles in Mushi Pro’s short-lived “Animerama” series, A Thousand & One Nights (1969), Cleopatra (1970) and Belladonna of Sadness (1973), arrived at an interesting juncture in the history of Japanese animation and Osamu Tezuka’s Mushi Production.

The three titles in Mushi Pro’s short-lived “Animerama” series, A Thousand & One Nights (1969), Cleopatra (1970) and Belladonna of Sadness (1973), arrived at an interesting juncture in the history of Japanese animation and Osamu Tezuka’s Mushi Production.

Tezuka entered the world of animation at the beginning of the 1960s, working on several features by Toei Animation, beginning with Alakazam the Great (1960), a feature-length rendition of the Ming dynasty literary classic Journey to the West. His Mushi Production would enjoy a dual reputation for both art-house pieces like Tale of a Street Corner (1962) and Pictures at an Exhibition (1962), alongside populist children’s entertainment, often based on Tezuka’s own manga, such as Astro Boy (1963-66) and Jungle Emperor (1965).

But neither of these strands proved profitable, largely due to Tezuka’s habit of dramatically low-balling the prices of his productions in an attempt to hold off competitors. Tezuka might have been many things, but a businessman he certainly wasn’t. The Animerama series came about from the flawed logic that, difficult as it was to make money catering for the younger family TV audience, it might be more lucrative to use Tezuka’s name to target an untapped demographic for adult-themed animation at the cinema.

One assumes that Tezuka hadn’t taken time to look at how domestic box office attendance had plummeted across the decade. By this point, the major studios of Shochiku and Toho had already drastically cut back on production, while Daiei, the company that had brought the world Rashomon and Sansho the Bailiff, would file for bankruptcy in 1971. Just two years later, within months of Belladonna hitting the screens, Mushi Pro also went under.

Belladonna has heretofore been the best known of the three Animerama films, somewhat ironically given that its threadbare and inanimate approach reveals just how cash-strapped Mushi Pro had become. The German-language DVD release from Rapid Eye Movies in 2008 was followed by the much greater fanfare surrounding the Cinelicious theatrical reissue of its 4K restoration in 2016 and its UK home-viewing debut last year courtesy of Anime Ltd. It is also the least characteristic, with its patchwork of animation methods, peculiar psycho-sexual imagery and an eccentric choice of source material. As its director, Eiichi Yamamoto, points out in the interview included here, at the time of its production it was considered a stand-alone work, not as rounding off a trilogy.

A Thousand & One Nights is based on the same world-celebrated folk-tale sources as earlier Japanese animated features such as Iwao Ashida’s 48-minute monochrome work Princess of Baghdad (1948) and Toei Animation’s Arabian Nights: The Adventures of Sinbad (1962), directed by Taiji Yabushita from a script to which Tezuka himself contributed. The story of Cleopatra should similarly need little introduction, although the Mushi Pro rendition bizarrely wraps a superfluous metanarrative around it, in which intergalactic time travellers are whisked back from the distant future to intervene in an alien plot to subvert the course of human history.

A Thousand & One Nights is based on the same world-celebrated folk-tale sources as earlier Japanese animated features such as Iwao Ashida’s 48-minute monochrome work Princess of Baghdad (1948) and Toei Animation’s Arabian Nights: The Adventures of Sinbad (1962), directed by Taiji Yabushita from a script to which Tezuka himself contributed. The story of Cleopatra should similarly need little introduction, although the Mushi Pro rendition bizarrely wraps a superfluous metanarrative around it, in which intergalactic time travellers are whisked back from the distant future to intervene in an alien plot to subvert the course of human history.

The Animerama films as a whole have been often misrepresented by foreign critics. While the people at Third Window deserve a pat on the back for releasing these two films in such beautiful transfers, they also warrant a slap on the wrist for perpetuating the myth that these were “X-rated animation.” They certainly weren’t in Japan, where they evaded a classification from the censorship body Eirin as “adult films”. Nor did they get an X-rating in the United States, where a desperate Tezuka flogged off Cleopatra to the minor distributor Xanadu Productions in order to hold off his company’s insolvency.

Xanadu dubbed the film and retitled it Cleopatra: Queen of Sex, falsely advertising it as the first X-rated animation to be released in America. In fact, it was never submitted to the MPAA, and it is doubtful it would have gained an X-certificate anyway. Even if it had, it would have been pipped at the post by Ralph Bakshi’s Fritz the Cat (1972), which hit cinemas a week before it.

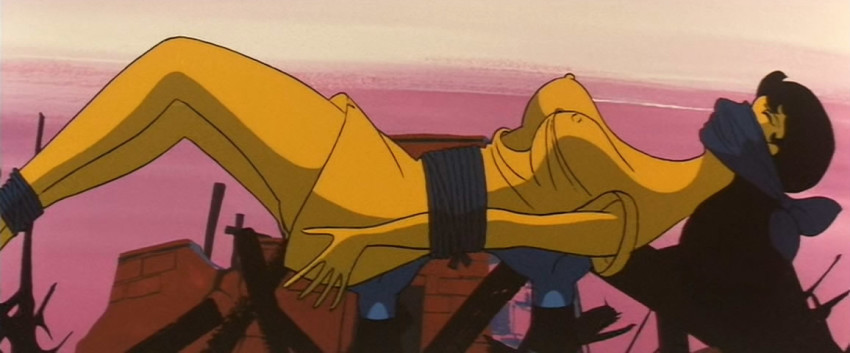

Still, by Western standards of the time, the Animerama films certainly stepped beyond the boundaries of the merely risqué, although unlike the more high-minded and straight-faced depictions of Pandora’s Box bursting asunder in Belladonna, they adopt a more Rabelaisian (some might say puerile) approach. The slave girl, Miriam bewitches our hero after her chador is whipped from her to expose her bare body in the opening slave market scene of A Thousand & One Nights, and remains largely unclothed throughout, as does the eponymous queen of Cleopatra, following her dramatic make-over by a mad Frankenstein-like scientist.

Toilet humour abounds, especially in the second film, with lots of peeing and pooing gags, notably in a scene in which Caesar is suddenly stricken with what might be euphemistically termed the Pharaoh’s revenge, and dashes frantically in search of a vacant toilet stall. Hints of bestiality also surface when one of the lustier time travellers, Rupa, winds up in the body of a leopard with the hots for the fabled beauty of the Nile.

While the cultural, racial and sexual politics undoubtedly belong to another age, the films certainly have their charms, and also considerable merits. The character designs and animation adhere much more closely to the conventions of their day rather than the more outré approach of Belladonna, although both feature love scenes abstracted into sinuous pulsating lines, anticipating the approach embraced more sensationally in this final title. The use of colour, light and texture really impresses, as do the facial expressions at times, and there are some beautiful background designs that really serve to remind you just how much modern animation has lost in its transition to 3D computer graphics.

Both films are a stylistic hotchpotch, especially Cleopatra, the framing device of which eccentrically features live performers with animated heads. A Thousand & One Nights hangs together a lot better than its follow-up, which was thrown together with a diminished budget and a far bigger workload for its animators, while Cleopatra also suffers in hindsight through a reliance on contemporary cultural references and in-jokes, such as an impromptu appearance of Astro Boy in one cutaway, and catchphrases from its voice actors that will sail over the heads of non-Japanese viewers.

Both films are a stylistic hotchpotch, especially Cleopatra, the framing device of which eccentrically features live performers with animated heads. A Thousand & One Nights hangs together a lot better than its follow-up, which was thrown together with a diminished budget and a far bigger workload for its animators, while Cleopatra also suffers in hindsight through a reliance on contemporary cultural references and in-jokes, such as an impromptu appearance of Astro Boy in one cutaway, and catchphrases from its voice actors that will sail over the heads of non-Japanese viewers.

Elsewhere the postmodern aspects are far more successfully integrated. There is a virtuoso parade scene following Caesar and Cleopatra’s return to Rome, referencing iconic works of a panoply of artists including Degas, Modigliani, Botticelli, Picasso and Bosch. Elsewhere, a fight scene unfolds using the slow-motion and action replays of television sports shows, while Caesar’s assassination is realised in the style of Kabuki.

Given that they were produced by Mushi Pro and were the brainchild of Tezuka, it seems reasonable enough to view the two titles as “Tezuka films”. Consequently, it would have been a natural choice to bring in the author of The Art of Osamu Tezuka: God of Manga, Helen McCarthy, for what is (surprisingly) her very first set of commentaries. McCarthy manages to fit in a lot of words into a cumulative three-hour running time, enthusiastically drawing attention to the more striking visual aspects of the films, while pointing out elements of Tezuka’s style and resonances of literary inspirations.

She also gives some background on other notable figures involved in the productions, like the pioneering avant-garde musician Isao Tomita, who composed the soundtracks for both. She also points out her reservations with Cleopatra during the opening credits, later mentioning that if the film seems a little slapdash, it may be because the hyperactive Tezuka, still at the relatively young age of 40, had his hands full with numerous other projects, including overseeing the TV animations of Vampire and Dororo, directing the two short films Misuke in The Land of Ice and One Short Time, and multiple manga.

But Eiichi Yamamoto, the man actually credited as directing A Thousand & One Nights and “co-directing” Cleopatra, is rather side-lined in these discussions. It takes half an hour in the second film for him to even get a mention, even though we can easily spot echoes of his previous experimental shorts. For example, the eye-catching frame-within-a-frame dialogue sequence in Cleopatra is carried over from Osu (1962), Yamamoto’s innovative portrayal of a marital murder through the eyes of the family cat.

But Eiichi Yamamoto, the man actually credited as directing A Thousand & One Nights and “co-directing” Cleopatra, is rather side-lined in these discussions. It takes half an hour in the second film for him to even get a mention, even though we can easily spot echoes of his previous experimental shorts. For example, the eye-catching frame-within-a-frame dialogue sequence in Cleopatra is carried over from Osu (1962), Yamamoto’s innovative portrayal of a marital murder through the eyes of the family cat.

Fortunately, Yamamoto himself is on hand to provide the real treat of this release, a lengthy and exhaustive interview in which he provides fascinating background on his changing relationship with Tezuka. Certainly one gets the impression from Yamamoto that the films were completed in spite of rather than because of Tezuka, who is presented as more an ideas man than an actual doer, spreading himself too thinly and taking a largely hands-off role on the films that bore his name.

Yamamoto also reveals that the hypnotic impressionistic “evocations” of love-making were inspired by the paintings of surrealist Hans Bellmer, and that the only problems with the censorship board Eirin was a single shot in Cleopatra of the Egyptian queen’s buttocks, reduced to half a dozen plain lines. My only critique is that Yamamoto’s recollections could have done with a bit of illustrating or livening-up in editing, rather than being delivered as a single 53-minute take in a fixed camera position. Nevertheless, it is fascinating stuff. The package also includes essays by Simon Abrams, who fills in a number of areas surrounding the production and release of the two films that neither McCarthy nor Yamamoto mention.

Two titles packaged together on Blu-ray for £24.99 (or £9.99 on DVD) already represents astonishing value for money, and for those interested in the history of Japanese animation, the interview with Yamamoto will be worth the admission price alone. The films themselves are likely to divide opinion, although they are certainly spirited, energetic works with a ribald character. But given their historical importance and lack of availability in any other format, this has to be an essential purchase.

Jasper Sharp is the author of The Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema. Cleopatra and A Thousand & One Nights are released on UK Blu-ray by Third Window Films.

1001 Nights, anime, Animerama, cinema, Cleopatra, Eiichi Yamamoto, Japan, Jasper Sharp, Osamu Tezuka

Leave a Reply