Books: Nightmares in the Dream Sanctuary

April 11, 2020 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

Donna Kornhaber’s new book on animation and war begins with an electrifying account of an afternoon in 1899, when the Ladies Welfare Committee for Soldiers and Sailors staged the premiere of Arthur Melbourne-Cooper’s one-minute “Matches Appeal.” The Empire, in Leicester Square, was the venue at which the world’s first recorded screening of an animated film took place, with an animated advert in which the Bryant & May company promised to send a personalised box of matches to every British soldier fighting in the Boer War.

Donna Kornhaber’s new book on animation and war begins with an electrifying account of an afternoon in 1899, when the Ladies Welfare Committee for Soldiers and Sailors staged the premiere of Arthur Melbourne-Cooper’s one-minute “Matches Appeal.” The Empire, in Leicester Square, was the venue at which the world’s first recorded screening of an animated film took place, with an animated advert in which the Bryant & May company promised to send a personalised box of matches to every British soldier fighting in the Boer War.

But then she leaps into the future, to a winter’s day in Moscow in 1983, when a very different film received its premiere. Garri Bardin’s “Conflict” also features animated matchsticks, but was a very different presentation with a severe anti-war message.

These two moments in cinema history mark the broad parameters of Kornhaber’s just-published Nightmares in the Dream Sanctuary, in which she investigates the relationship of animation and war, not merely as propaganda, but as protest, resistance and memorial. She is intrigued by the ways in which film can be used to tell outrageous lies about the acceptability of war, or to confront viewers with unwelcome truths about its costs, but also in which animation, in its plastic relation to reality, can prove ideally suited for depicting a world turned upside-down.

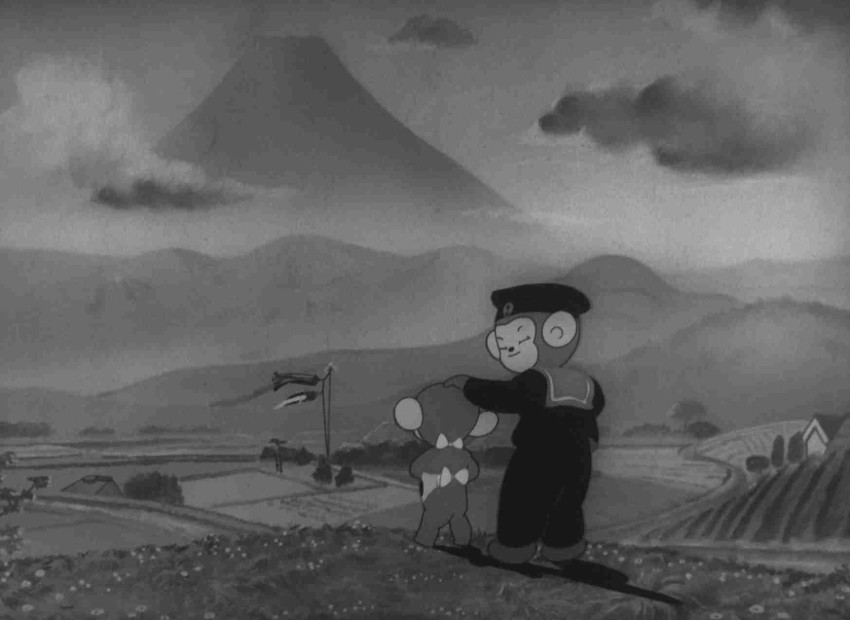

She observes, for example, the ridiculous conceit of Momotaro, Sacred Sailors (1945, pictured above), that a Japan that was actually on the edge of starvation could have seriously considered a paratrooper invasion of the United States. And she considers the contradiction in the widespread assumption that animation is a children’s medium, versus the idea that “the medium of Mickey Mouse” might have something to say about napalm and the Holocaust. Inevitably, this is a journey that takes her to Barefoot Gen and Grave of the Fireflies.

She observes, for example, the ridiculous conceit of Momotaro, Sacred Sailors (1945, pictured above), that a Japan that was actually on the edge of starvation could have seriously considered a paratrooper invasion of the United States. And she considers the contradiction in the widespread assumption that animation is a children’s medium, versus the idea that “the medium of Mickey Mouse” might have something to say about napalm and the Holocaust. Inevitably, this is a journey that takes her to Barefoot Gen and Grave of the Fireflies.

Although Kornhaber does name-check Japanese animation in her account, her work is more valuable for the non-Japanese obscurities it unearths, beginning with the In the Jungle There is Much to Do (1974), made in Uruguay by Walter Tournier during a period of national unrest, and Raymond Jeannin’s Nimbus Liberated (1944), in which the family of a much-loved French cartoon character is murdered by Mickey Mouse and sundry other Allied icons, flying a squadron of B-17s against Vichy France. Nor does she limit her study to overt propaganda and “war” animation, since she is also fascinated by the use of animation as a means of protest – Czech animators standing up to Stalin in the Cold War, for example, or the unknown creators whose The Extremists’ Game Destroys the Innocent (2015) imagined sectarian conflict within Islam as a savage game of human chess.

Kornhaber trains a sophisticated eye on the subtexts in wartime animation, such as the anti-Japanese message that remained buried in the Wan brothers’ Chinese feature Princess Iron Fan (1943), even though by the time they finished it, they were living under Japanese occupation. She also has an interesting approach to Kenzo Masaoka’s Cherry Blossoms (1945), a film that was banned by the US Occupation forces for evoking too many icons of WW2. Kornhaber ponders whether Masaoka was deliberately revisiting such imagery – including Mount Fuji as well as the titular sakura, now indelibly associated with kamikaze pilots – or if his animators were just so steeped in it after 15 years of war that it was second nature to them.

Later chapters include many similarly incisive considerations of everything from that time an unlicensed Mickey Mouse invaded Vietnam, to the wonderfully titled Pink Panzer, to animated works from Israel, India, the former Yugoslavia, and Africa. Persepolis and Waltz with Bashir both get a look-in, as does The Sinking of the Lusitania, in a provocative final chapter that considers the uses of “memorials” within the world of animation and war. It’s here, of course, that both Barefoot Gen and Grave of the Fireflies, two stand-out works in an otherwise mediocre sub-genre of commemorative WW2 anime, get their due.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Sacred Sailors: The Life and Work of Seo Mitsuyo. Nightmares in the Dream Sanctuary: War and the Animated Film by Donna Kornhaber is published by the University of Chicago Press.

Leave a Reply