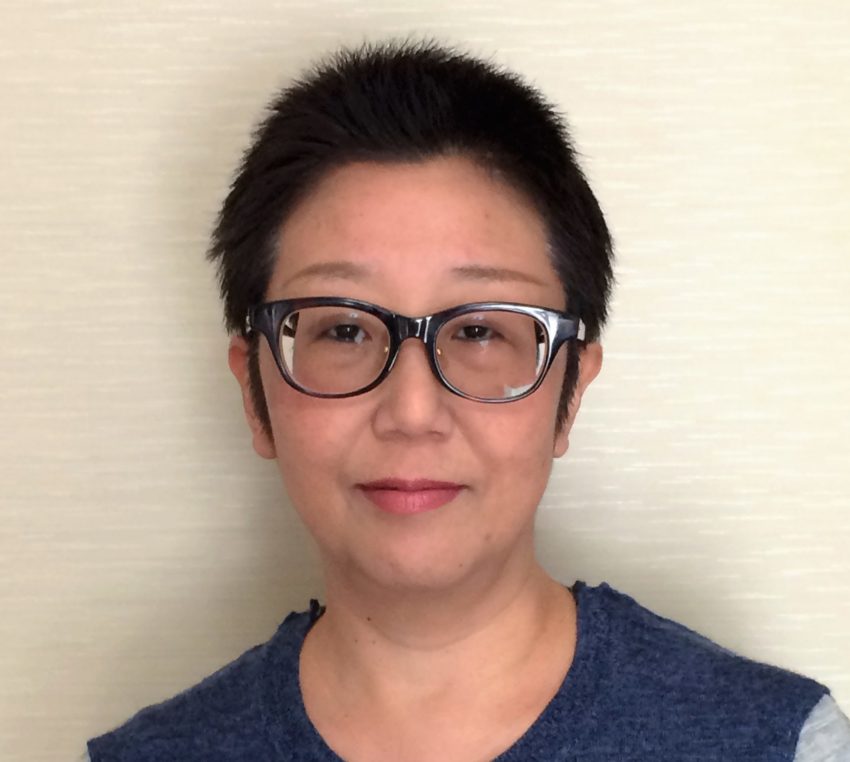

Interview: Yukari Takeuchi

May 30, 2021 · 0 comments

By Gianni Simone.

Yukari Takeuchi, CEO of Seven Seas, LLC. Takeuchi is an entertainment industry veteran who for more than 30 years has been involved in many aspects of the animation business, from production and distribution to licensing and merchandising.

An early participant in indie mega-fair Comiket during her college years, Takeuchi joined TMS Entertainment after graduation. TMS is one of the oldest and most famous animation studios in Japan, best known for the Lupin III and Anpanman franchises and such cult movies as Akira. Takeuchi initially worked in the production department before moving to the business side of operations.

“I started as a production assistant,” she says. “At that time, TMS, like Toei and Tezuka Productions, used to do a lot of work for American projects, and they needed someone who could speak English. Companies like Disney, Warner Bros and Fox would do the pre-production in-house before sub-contracting the actual production work to Japanese studios because they were much cheaper. A couple of supervisors would be sent to Japan, and part of my work was to assist them as a translator and interpreter.”

According to Takeuchi, this was a well-paid but rather frustrating experience for the animators who worked on those projects, because their names never appeared on the movie titles. Eventually, when the yen rose up in value against the dollar, American companies began to look for even cheaper animators in Taiwan, Korea and even China.

“Now we have reached a point in which Chinese productions have become so good and their budget so high that they have started hiring Japanese animators for their projects,” Takeuchi says laughing. “Even Korea has caught up with Japan in terms of the production budget.”

As TMS’s operations were growing, Takeuchi was assigned to manage all the distribution contracts, in both the domestic and overseas market. “An important change occurred with the home video entertainment boom of the 1990s,” she says. “Lots of otaku fans started to buy special video and DVD editions featuring commentary from the director and the animators, digital remasters, etc. bringing a lot of money to the studios. This, in turn, attracted the attention of many record labels like Avex and King Records that began to sponsor or support the shows as they saw animation as an ideal medium to reach more music fans.”

The new attention generated by anime’s growing success both at home and abroad attracted partners from everywhere, eventually leading to the consolidation of the so-called media mix business model, a strategy where multiple platforms (television, cinema, games, toys and merchandise, cell phones, etc.) work together to maximize market penetration and generate more profits. “This model has the advantage that investment risks are shared among several companies,” Takeuchi says. “Even now, the only companies that have enough financial muscle to fund a project all by themselves are NHK (Japan’s national TV broadcaster) and Netflix.” [e.g. Yasuke, pictured]

However, the media mix has its downside too, and already at the turn of the century, many people were saying that it was not working well. “For example, some consortiums consist of up to ten or 12 companies,” Takeuchi says, “and you always have to check each of them before reaching a decision. That makes things quite complicated. Unfortunately, for the time being, this is the only way new works can be produced.”

After working for 20 years at TMS, Takeuchi joined the video game company Sega, where she worked on the licensing of consumer products (plushies, figures, stationery), before opening her own agency. “Seven Seas is actually a one-person company, so basically I’ve become a freelance,” she says. “This gives me more independence and the chance to work for different studios and projects at the same time. For example, I’m currently handling character and brand licensing, and I’m in charge of overseas contract management for Netflix and Toho, the major film company that is famous for producing Godzilla, My Hero Academia, Your Name and Weathering with You.”

Regarding the foreign market for Japanese animation, Takeuchi says that anime for kids can sometimes be a hard sell because of content issues. “Crayon Shin-chan,” Takeuchi says, “is a typical title that though hugely popular in Japan, has had problems cracking the Asian market.” The main problem is that Shin-chan’s behavior, his disrespectful attitude toward elders and some of his antics, like the “butt-shaking” dance, are seen – even in Japan – as a negative influence on children. As a consequence, when shown abroad, this anime can only be aired in the kids’ time slot after being heavily censored.

Takeuchi says that the anime industry has experienced many changes during the last thirty years. “For one thing, studios have become more cautious when launching a new title,” she says. “In the 1970s and 1980s, they used to produce a year-worth of stories (i.e. 52 episodes) of such anime as Heidi and Mazinger Z. Even Gundam, the original run of which in 1979 was only mildly popular, ran for 43 episodes. Now, on the contrary, they only produce 12 or 13 installments, and then see what happens.”

Being more cautious also means that original stories are now considered too risky because one cannot predict whether fans are going to like them or not. “It’s much easier to base new anime series on successful manga or game titles,” Takeuchi says, “as they already offer a built-in fan base. Some 80% of new anime fall under this category.”

Another recent trend has been an increase in anime that pander to adult viewers and hardcore otaku tastes at the expense of family-friendly titles. They typically air after midnight and feature comparatively more erotic scenes, violence and gambling. “On the other hand,” Takeuchi points out, “the overseas market has grown so much that the studios now create new titles with an eye to foreign fans. Foreign influence is also being felt on the production level, with more investment coming in from the US, China and Korea.”

Last but not least, there are now stronger ties with musicians and the record industry. “For example, Sony Music Entertainment is part of the consortium behind Demon Slayer,” Takeuchi says, “so it’s only natural that the anime theme song was performed by LiSA who belongs to Aniplex, a Sony sub-label.”

2020 was obviously a difficult year for animation. Because of COVID-19, many productions ended up running behind schedule, while in other cases, completed works could not be released because of problems with theater bookings. One such case is the 31st Anpanman movie, delayed to 2021. “The problem with Anpanman,” Takeuchi says, “is that its target audience are small kids, so they must be very careful about when and how the film is released.”

Coronavirus-related problems aside, Japanese animation seems to do very well, especially abroad. According to the 2019 Anime Industry Report, the overseas market now exceeds one trillion yen, with North America accounting for almost half of the international market, followed by Asia (31.5%) and Europe (11.4%). The United States, of course, is the biggest client, with 467 contracts, followed by Canada (417) and China (281).

However, the same report shows that the overseas market is slowing down. “This is mostly due to problems with the Chinese market,” Takeuchi says. “China is currently one of the biggest markets for Japanese animation (30-40% or even more of the streaming-related profits come from this country), but the Chinese government decided to impose stricter regulations on the Internet due to its growing impact. In addition, it decided to apply to Internet content the same kind of censorship it had previously used to regulate conventional media content. As a result, Chinese buyers have become reluctant to import Japanese titles.”

While the anime industry as a whole seems to do well, the media are full of stories about animators being paid poorly. According to Takeuchi, this is a consequence of the way the industry works. “Let’s suppose that Toei is making a new TV anime,” she says. “Now, a typical series consists of 12 episodes, and Toei must deliver a new episode every week, but they probably can’t do everything themselves. Though digital animation is becoming more common, many parts are still hand-drawn. This is a very time-consuming process, so they subcontract part of the project to a few smaller studios. Now, the original production budget may be fairly big, but every partner takes a piece of the cake, including Toei that in turn uses part of that money to pay the smaller studios. But that’s not the end of the story. Even the subcontractors may not be big enough to handle the work they were assigned, so they ask even smaller studios to help. These studios are constantly in danger of going bankrupt and are the ones who suffer the most because the money trickling down to them is just a tiny fraction of the original budget.”

Asked if making anime has become easier, Takeuchi says she is not so sure. For instance, Crunchyroll and Netflix have been huge game-changers in the way anime is now consumed, and online streaming has brought a lot of money to the industry. However, this new distribution model poses unforeseen problems for the producers. “Before, people would watch anime on TV – either commercial channels or pay-TV– at an established hour,” she says. “This gave the media mix consortiums a chance to check the ratings and see how popular a title was. This way, they could come up with good estimates of how many people would buy related merchandise or a manga or game based on that work. But now that Crunchyroll and Amazon Prime have become the main distributors, people can watch a certain show any time they want. That doesn’t pose a particular problem for music or game companies because even their products are often sold online. However, if you sell physical products like figures or stationery, you have to make a big investment up-front without being guaranteed a return.

“Another problem related to the new distribution model is that in the past, the studios could earn money from two sources: through home entertainment (videos, DVDs, etc.) and by selling their rights to TV channels. But now, most people watch anime through streaming and video-on-demand, so the money comes from only one source.”

Though Takeuchi is not particularly pessimistic about the future of Japanese animation, she says that too many anime works are being made right now. “When I started my career,” she says, “I believe they were making about 30-40 shows in one year; now the annual output is probably more than 100, meaning that many more animators are required. At the same time, a lot of studios can’t support the late-night slot, which is not as lucrative as before anyway.

“Last but not least, Netflix and Amazon are currently investing lots of money in animation, but in a few years they will probably start focusing on a small number of good properties that sell well. So my impression is that the anime industry is going toward a contraction in the number of new works actually created.”

Gianni Simone is the author of Otaku Japan.

Leave a Reply