Isao Tomita 1932-2016

May 8, 2016 · 0 comments

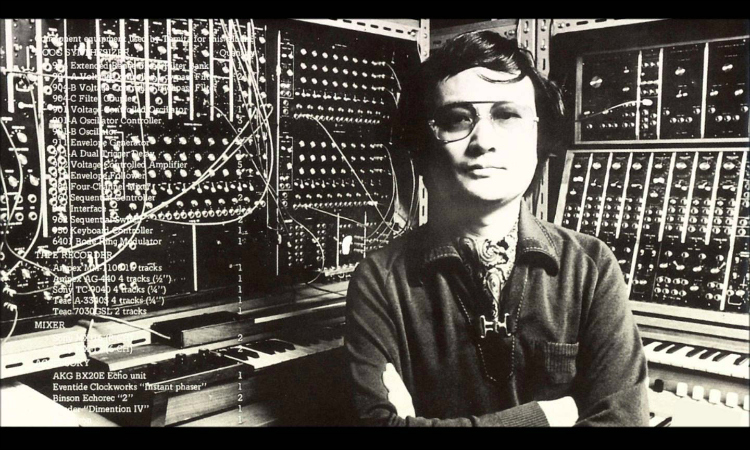

Isao Tomita, who died on 5th May, was not just a composer, but also a performer and a pioneer in electronic music. Born in what is now Suginami ward in Tokyo, he spent much of his childhood in China, where his father Kiyoshi was a physician at the Kanebo textile mill in Qingdao. It was during this time that he visited Beijing’s Temple of Heaven, a site renowned for the unique sound-qualities of its Triple-Echo Stones and Circular Echo Wall. The experience inspired a life-long obsession with acoustics and the production of sound.

Isao Tomita, who died on 5th May, was not just a composer, but also a performer and a pioneer in electronic music. Born in what is now Suginami ward in Tokyo, he spent much of his childhood in China, where his father Kiyoshi was a physician at the Kanebo textile mill in Qingdao. It was during this time that he visited Beijing’s Temple of Heaven, a site renowned for the unique sound-qualities of its Triple-Echo Stones and Circular Echo Wall. The experience inspired a life-long obsession with acoustics and the production of sound.

“When I was a child, Japan was closed to western music,” he told Tokyo Weekender. “This was during the Second World War. At the end of the war, a lot of western music started to be broadcast on the radio. Jazz, pop songs, and classical music was filling the airwaves of Japan. To me, that music sounded like it was coming from aliens in outer space.”

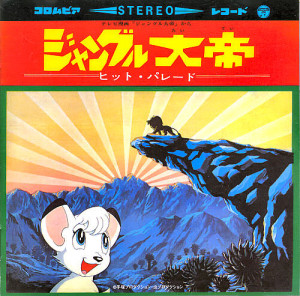

Tomita studied art history at Tokyo’s prestigious Keio University, taking private lessons after hours in composition and orchestration. Fresh out of college, he seized the opportunity to take work in the burgeoning world of new media, composing radio jingles, TV theme songs and soundtracks. He composed the score for the first of Japan’s Sunday-night historical taiga dramas, Life of a Flower, but achieved his most recognisable success in 1965 with the music to Osamu Tezuka’s Jungle Emperor (known in the US as Kimba the White Lion).

Notorious for his attempts to industrialise cartoons, Tezuka applied his “image bank” philosophy to the music itself, asking Tomita to rustle up a series of generic mood pieces that could be slotted in where relevant, but also reused. Tomita duly provided a melancholy theme, a happy theme, an action theme and several others. He also inadvertently started a fight among Tezuka’s staff, by asking someone to provide choral lyrics for a moment when Leo the lion sees the spirit of his late father outlined in stars in the sky. Someone at Mushi Production dashed something off in the midst of a busy lunch-hour, and thought no more of it until Tomita’s music, repurposed as a symphony, became a runaway hit in album form.

Notorious for his attempts to industrialise cartoons, Tezuka applied his “image bank” philosophy to the music itself, asking Tomita to rustle up a series of generic mood pieces that could be slotted in where relevant, but also reused. Tomita duly provided a melancholy theme, a happy theme, an action theme and several others. He also inadvertently started a fight among Tezuka’s staff, by asking someone to provide choral lyrics for a moment when Leo the lion sees the spirit of his late father outlined in stars in the sky. Someone at Mushi Production dashed something off in the midst of a busy lunch-hour, and thought no more of it until Tomita’s music, repurposed as a symphony, became a runaway hit in album form.

The 15-track Jungle Emperor album would become the first anime-themed LP, selling 100,000 copies – generating lucrative royalties for Tomita, but also for the unknown lyricist. The main suspect was animation director Eiichi Yamamoto, leading to further arguments about whether he had written the words during a working day, thereby forfeiting his royalties to the company, or during one of the 250 hours of unpaid overtime he had clocked. Eventually, Mushi’s managers ruled in favour of themselves, fearful of setting a precedent. It was not the only copyright dispute over Jungle Emperor. As the commercial break rolled around, Tomita was surprised to discover a pastiche of his theme song, now adapted by the programme’s sponsor to underscore an advert for Sanyo Electrics.

Tomita’s work remained a regular feature of Mushi Production’s cartoons, including Princess Knight and Cleopatra. As Tezuka’s company stalled in the late 1960s, Tomita started his own, becoming one of the founders of Group TAC. There he might have slipped into the shadows composing jingles and background music, were it not for his involvement in the early days of electronica. “I arrived to the conclusion that everything that could be achieved in orchestration has already been done in Wagner’s time,” he said in an interview, “and, eventually, I realised that I wanted to make my own music using my own sounds.”

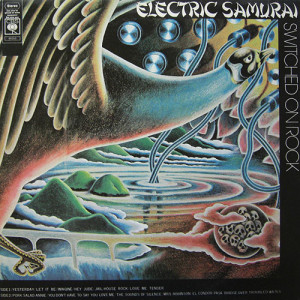

Intrigued by the work of Wendy Carlos with Switched-On Bach, Tomita flew to Buffalo, New York, in 1970 to buy a Moog III-P synthesiser direct from the maker. Stopped at Japanese customs with an unidentifiable machine, he pleaded with officials that it was a musical instrument, but was unable to prove it by playing it for them. A month later, when his expensive toy finally cleared customs, he was left with a pile of machinery and a 15-page manual that explained almost nothing. “I felt like I just paid loads of money for a big chunk of metal. If I can’t make proper sounds, it’s just junk! Also, since Moog was a new kind of instrument, I didn’t have a clue how it was supposed to sound because there wasn’t anything to compare it to. So I started emulating existing sounds, such as a bell or a whistle, and went from there.” His first effort, Switched-On Rock, released under the chop-socky monicker of “The Electric Samurai” included synthesiser versions of Beatles songs and Simon & Garfunkel.

Intrigued by the work of Wendy Carlos with Switched-On Bach, Tomita flew to Buffalo, New York, in 1970 to buy a Moog III-P synthesiser direct from the maker. Stopped at Japanese customs with an unidentifiable machine, he pleaded with officials that it was a musical instrument, but was unable to prove it by playing it for them. A month later, when his expensive toy finally cleared customs, he was left with a pile of machinery and a 15-page manual that explained almost nothing. “I felt like I just paid loads of money for a big chunk of metal. If I can’t make proper sounds, it’s just junk! Also, since Moog was a new kind of instrument, I didn’t have a clue how it was supposed to sound because there wasn’t anything to compare it to. So I started emulating existing sounds, such as a bell or a whistle, and went from there.” His first effort, Switched-On Rock, released under the chop-socky monicker of “The Electric Samurai” included synthesiser versions of Beatles songs and Simon & Garfunkel.

Tomita’s investment in the Moog synthesiser paid off behind the scenes – he was soon responsible for many of the short but ubiquitous theme tunes for shows like NHK’s News Bridge, News Centre and News Wide – even members of the public with no interest in music would hear his work for several hours a year, in daily thirty-second bursts. He hired an assistant to deal with much of the dog-work, Hideki Matsutake, who would eventually put his experience to work as the music programmer and “fourth member” of the famous Yellow Magic Orchestra.

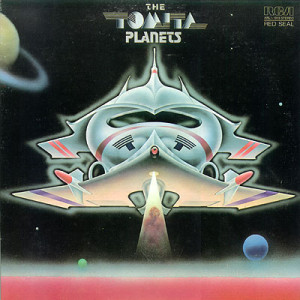

Tomita began experimenting with classical music on the synthesiser, hitting tough resistance in his native Japan, where record stores were unsure where to file him. He initially enjoyed greater success in America, with his reworking of Debussy in Snowflakes Are Dancing, and Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition. Not everybody liked his experiments – Gustav Holst’s daughter protested at his treatment of The Planets, and the album was withdrawn for a while from sale. Holst is now safely out of copyright, allowing the album that Tomita himself claims to be the centrepiece of his life’s work back into record stores. Its outer-space themes encouraged Tomita to pivot into what he called “space music”, riding the 1970s zeitgeist into a series of albums with sci-fi sensibilities and covers to match, most notably Kosmos (1978), which included a jaunty, whistling version of the Star Wars theme that is… something of an acquired taste. He achieved longer-lasting appreciation, and an entire new fanbase, when the same album’s Bach-derived A Sea Named Solaris appeared on the soundtrack to Carl Sagan’s Cosmos.

Tomita began experimenting with classical music on the synthesiser, hitting tough resistance in his native Japan, where record stores were unsure where to file him. He initially enjoyed greater success in America, with his reworking of Debussy in Snowflakes Are Dancing, and Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition. Not everybody liked his experiments – Gustav Holst’s daughter protested at his treatment of The Planets, and the album was withdrawn for a while from sale. Holst is now safely out of copyright, allowing the album that Tomita himself claims to be the centrepiece of his life’s work back into record stores. Its outer-space themes encouraged Tomita to pivot into what he called “space music”, riding the 1970s zeitgeist into a series of albums with sci-fi sensibilities and covers to match, most notably Kosmos (1978), which included a jaunty, whistling version of the Star Wars theme that is… something of an acquired taste. He achieved longer-lasting appreciation, and an entire new fanbase, when the same album’s Bach-derived A Sea Named Solaris appeared on the soundtrack to Carl Sagan’s Cosmos.

Critics of Tomita’s work often focus solely on the production of his electronic sounds, and not on his equally innovative attention to its placement. Tomita’s albums were key ingredients in hipster hi-fi, making clever use of stereo, quadrophonics and sub-woofers. His sales enjoyed new spikes every time a new format promised higher fidelity, right up to Blu-ray audio, which he embraced with ever more lavish concerts. Shortly before his death, he even created a concert for the Vocaloid virtual idol Hatsune Miku. “I had no idea that she was so popular,” he joked. “So, I was very pleased that she agreed to work with me.”

The more expensive your sound system, the more mileage you could expect to get from his performances. Listen to them today on the best of headphones, and his sonic spaceships still whoosh from ear to ear and over your head. In later life, Tomita did not limit himself solely to the acoustics of the lounge or headphones, conducting increasingly grandiose “Sound Cloud” experiments with concert halls and other venues, such as an outdoor rendition of the Blue Danube in Linz, Austria, in 1984 that bounced Johan Strauss’s waltz off the river itself. Such performances reached their peak in 2006 with his outdoor Symphony to Buddha, using a holy mountain as both a backdrop and a sounding board.

“I was often criticised for using an electronic instrument,” he once said, “but the sound of thunder has been around since the dawn of time, and that’s electricity.”

anime, Eiichi Yamamoto, Electric Samurai, Isao Tomita, Jonathan Clements, Jungle Emperor, Kimba the White Lion, Moog, Mushi Pro, music, obits, Osamu Tezuka, Princess Knight

Leave a Reply