Penguin Highway

February 23, 2020 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

Suddenly, there are penguins everywhere. And then there aren’t. Aoyama and his fellow townsfolk are confused by the infestation, but it may have something to do with that big silver sphere out in a meadow near the woods. Shouldn’t someone be doing something about that?

Suddenly, there are penguins everywhere. And then there aren’t. Aoyama and his fellow townsfolk are confused by the infestation, but it may have something to do with that big silver sphere out in a meadow near the woods. Shouldn’t someone be doing something about that?

So begins Penguin Highway, animated by director Hiroyasu Ishida at the Colorido studio, adapted for the screen by Makoto Ueda, from the 2010 novel by the poster-boy of Japanese post-modern science fiction, author Tomihiko Morimi.

A master’s graduate in Agriculture from Kyoto University, Morimi was first published while still a student, and many of his works draw deeply on the experience of living in the city that was Japan’s capital for a thousand years, and which remains an icon of old-world tourism and genteel sophistication. Morimi’s Kyoto is a riot of pop-up bazaars and student happenings, the thinnest of veneers over the rich, vibrant colours and culture of antiquity, where the sight of a geisha in full finery waiting for a bus is no more or less surreal than the revelation that said geisha could be a shape-shifting fox-spirit or crow-demon from Japanese mythology. For Morimi, the city’s periodic festivals and carnivals over-write the modern world with bursts of the fantastic.

Parallels are inevitable with the best-selling Haruki Murakami, not the least for Morimi’s shared penchant for nameless, slacker protagonists and pixie-dreamgirl muses, but in Morimi’s work the city itself becomes a nest of tall tales. Several of his books have been adapted into anime, including his Eccentric Family series, in which a group of shape-shifting racoon-dogs contend to become the secret master of the town. Also animated for television was The Tatami Galaxy, a time-loop in which a freshman’s luck in love is revisited and retooled through the simple dilemma of which Kyoto University hobby-club he should join. In the original novel of his Night is Short, Walk on Girl, the protagonist pursued an indifferent love interest through an academic year, dimly aware that she is merely a catalyst not only for his adventures on the journey, but for the romantic imaginings that he projects upon her. The 2017 anime version, screened at last year’s Scotland Loves Anime, increases the sense of the surreal by compressing the entire story, seasonal changes and all, into a single crazy night.

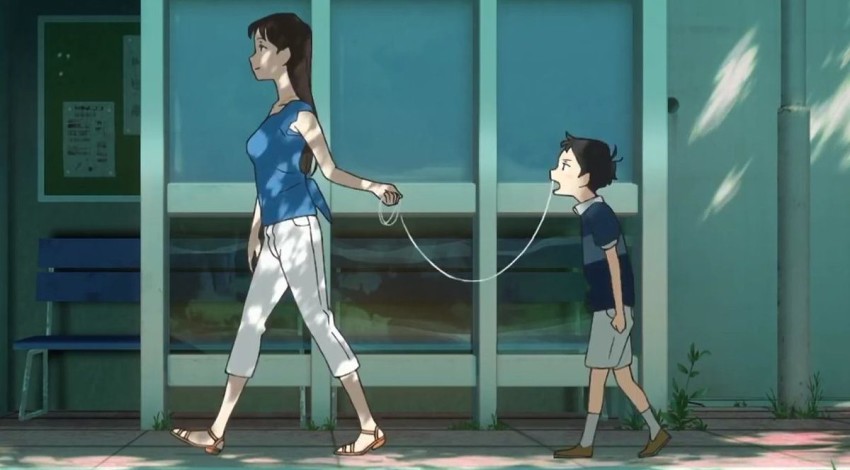

Penguin Highway represents a step away from Morimi’s usual stomping grounds. If it is set in Kyoto at all, it is in an anonymous suburb that might as well be anywhere, where Aoyama (voiced by Hana & Alice’s Yu Aoi), a self-assured boy-hero at a loose end during the long summer holidays, decides to probe a series of local mysteries.

Penguin Highway represents a step away from Morimi’s usual stomping grounds. If it is set in Kyoto at all, it is in an anonymous suburb that might as well be anywhere, where Aoyama (voiced by Hana & Alice’s Yu Aoi), a self-assured boy-hero at a loose end during the long summer holidays, decides to probe a series of local mysteries.

“The Penguin Highway novel came out just when Tatami Galaxy was on Japanese television,” admitted Morimi at a press conference. “The timing was very subtle, but they were two very different works, so it’s possible that people passing the shelves might not have noticed the Penguin Highway book. It’s been a long time now, but it will be a lot of help if the book sells more as a result of this film. My publishers will be happy at least!”

The original award-winning 2010 novel, reprinted multiple times in its native Japan, adds a single word to Arthur C. Clarke’s Third Law: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic-realism.” Since Aoyama is only ten, it barely seems to occur to him that penguin apparitions and a bizarre “silver moon” in the nearby forest are any weirder than any other puzzle to be solved. Aoyama is supremely confident in his dream world – he simply knows that he is destined for brilliant things, and is already preparing himself to disappoint all the women who will be heartbroken to discover that he has already chosen his future wife. He is a youth so callow that he fails to notice that his own self-belief is no stranger than the sight of penguins in the local meadow. The reason for their existence is simply a puzzle to be solved, a fustian riddle for him and his sidekick Uchida to investigate with the formation of a pompous “expedition team.”

The novel was praised in Japan for its artful capture of a ten-year-old’s mindset, an entirely unexpected protagonist for a complex story of inter-dimensional transport, gazing, baffled from the side lines as the adult investigators draw a series of blanks. Aoyama is supremely confident that he is destined for great things, even though his classmate Hamamoto can kick his arse at chess, and his Uchida is the one who puts in the legwork and makes the most crucial discoveries off-screen. All Aoyama really wants to do is impress The Lady – another of Morimi’s unattainable heroines – the dentist’s assistant and sometime babysitter who indulges his childish crush on her with minimal eye-rolling.

The novel was praised in Japan for its artful capture of a ten-year-old’s mindset, an entirely unexpected protagonist for a complex story of inter-dimensional transport, gazing, baffled from the side lines as the adult investigators draw a series of blanks. Aoyama is supremely confident that he is destined for great things, even though his classmate Hamamoto can kick his arse at chess, and his Uchida is the one who puts in the legwork and makes the most crucial discoveries off-screen. All Aoyama really wants to do is impress The Lady – another of Morimi’s unattainable heroines – the dentist’s assistant and sometime babysitter who indulges his childish crush on her with minimal eye-rolling.

If this were an adult science fiction tale, conceived in the mode of Arrival or Contact, then we would concentrate on the grown-ups as they experimented, posited, theorised and fell in love. But the science team tardily sent to investigate the town’s Fortean phenomena are barely glimpsed, while the camera stays instead with the summer-days camp-out of three children, exploring strange goings-on because it beats watching telly. Despite his lofty self-regard, Aoyama knows very little about the real world – growing up in a land-locked suburb, he’s never even been to the seaside, imparting the beach with the same mystical qualities alluded to in Alex Proyas’ Dark City. But if this makes the film sound overtly philosophical, it isn’t. Allusions to Plato’s cave, wherein the prisoners do not realise they are inmates, fly far over Aoyama’s head. The closest he comes to any deeper meaning is in the script’s repeated use of imagery from Lewis Carroll, particularly the “Jabberwock” creatures that seem to be in conflict with the penguins.

Japan’s national broadcaster, NHK, used to punt shows like this onto early-evening live-action telly all the time in the 1970s. I’m thinking of TV serials like Wipe Out the Town (1978), in which schoolchildren inadvertently phase into a fascist alternate reality, or Infrared Music (1975), in which telepathic schoolchildren are selected for preservation before the Earth’s imminent destruction. The most fondly remembered, of course, have already been remade as modern anime: Time Traveller (1972), which was animated as The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, and Challenge from the Future (1977), remade as Psychic School. One imagines producers at the new studio Colorido, thrashing around in search of rights to something similar – a kids’ classic that might bring in a multi-generational audience, only to realise that Morimi had written an all-new one, and that it was right under their noses.

Notably, such stories offered clear narrative closure and answers to the actual questions posed. It’s far more difficult to summarise the plot of Penguin Highway in print, because it is never fully resolved, which means that simply describing the mystery takes you all the way to the last fifteen minutes of the film. Like the two-dimensional square that narrates Edwin Abbott’s sci-fi classic Flatland, mere human beings like us have trouble getting our heads around the shape of creatures from another dimension, but that is part of Morimi’s artistic achievement – in using a pre-teen narrator, he turns us all into children, trying to make sense of wonders beyond our imagination.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History.

Penguin Highway is released in the UK by Anime Limited.

anime, Japan, Jonathan Clements, penguin highway, Scotland Loves Anime, tomihiko morimi

Leave a Reply