Takahata: The Exhibition

July 13, 2019 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

The magnificent exhibition “Takahata Isao: A Legend in Japanese Animation” (the title puts Takahata’s family name first, Japanese style) runs at Tokyo’s National Museum of Modern Art until 6th October. Struggling to take in Takahata’s career of over 50 years, I was reminded of an immodest quip made by Orson Welles in the 1930s, even before he’d debuted as a filmmaker. Welles introduced himself to an audience as a writer, producer, stage director, actor and magician. Then he asked: “Why are there so many of me and so few of you?”

The magnificent exhibition “Takahata Isao: A Legend in Japanese Animation” (the title puts Takahata’s family name first, Japanese style) runs at Tokyo’s National Museum of Modern Art until 6th October. Struggling to take in Takahata’s career of over 50 years, I was reminded of an immodest quip made by Orson Welles in the 1930s, even before he’d debuted as a filmmaker. Welles introduced himself to an audience as a writer, producer, stage director, actor and magician. Then he asked: “Why are there so many of me and so few of you?”

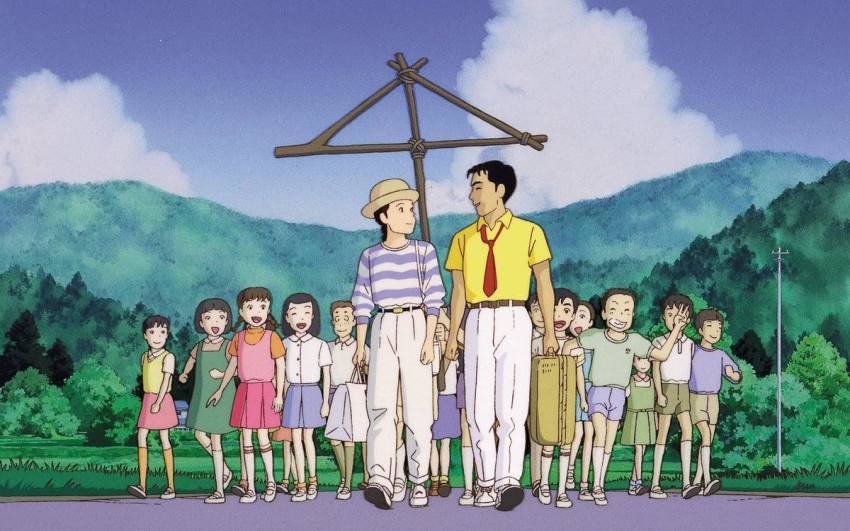

If Takahata had wished, he could have used Welles’ line on many artists more famous than himself, including his colleague Hayao Miyazaki. Takahata made tragedies and comedies; boys’ adventures and female introspections; cartoons for infants, and art films suitable for anyone looking outside the mainstream. He reinvented anime at least three times, or more. He directed Little Norse Prince and Heidi and Grave of the Fireflies, and also Chie the Brat and Only Yesterday and Princess Kaguya. He supported other directors’ animation, from Nausicaa to The Red Turtle. He translated French poetry, made an epic live-action documentary on Japanese canals, and wrote on the history of world art.

The exhibition covers nearly all that, though I was disappointed Red Turtle was missed. This is an extremely friendly exhibition for Anglophones; it offers an English-language audio guide for a small surcharge, with about 40 minutes of material, and the information captions on the walls have English translations. There are also a great many untranslated original Japanese documents, some translated on the spot by my friend Carlos Nakajima. They’re covered later in this review

Many of the displays speak for themselves, representing Takahata’s decades of anime through cels, layouts, animation drawings, backgrounds, paintings, storyboards and sketches. There are especially large sections devoted to the first Takahata-directed feature, the fantasy The Little Norse Prince; to Heidi, Takahata’s most beloved anime in Japan; and to Pom Poko, represented by hundreds of colourful sketches brimming with tanuki, yokai and furry testicles.

The exhibition starts with a large timeline display, while the museum text throughout stresses Takahata’s evolution. For instance, the section on Takahata’s 1979 series Anne of Green Gables highlights how he used the different viewpoints of young and old in the series. In particular, he set the fanciful, skittish Anne against her sternly serious foster guardian Marilla, to develop an objective, detached treatment of the characters. (However, I’d argue that Takahata’s objective characterisation was visible in other ways in Prince, made a decade earlier.)

Takahata’s devotion to detail is clear even if you don’t read Japanese. For Prince, he drew up charts which looked like heart monitors to show the characters’ levels of tension through the story, and diagrams depicting their relationships and suspicions. For Heidi, he filled notebooks with Alpine cheese-making and the lives and habits of mountain goats. For Anne, he drew up timelines about how the girl aged through the series, and perused Lucy Maud Montgomery’s book, picking out English words and phrases like “gingham,” “buttercups” and “the dog at his master’s grave.”

Takahata’s devotion to detail is clear even if you don’t read Japanese. For Prince, he drew up charts which looked like heart monitors to show the characters’ levels of tension through the story, and diagrams depicting their relationships and suspicions. For Heidi, he filled notebooks with Alpine cheese-making and the lives and habits of mountain goats. For Anne, he drew up timelines about how the girl aged through the series, and perused Lucy Maud Montgomery’s book, picking out English words and phrases like “gingham,” “buttercups” and “the dog at his master’s grave.”

Although Takahata is tagged as an animation director who didn’t draw, the exhibition highlights how involved he was in storyboards. He may not have done the pictures, but he busily annotated them with notes and instructions. He was doing this even in his mid-twenties on the 1961 animated film The Orphan Brother (aka The Littlest Warrior) on which Takahata was assistant director – newly discovered storyboards are displayed.

The exhibit also unearths storyboards drawn by Takahata himself for a 1978 TV series, The Story of Perrine. While the images are very simplified, they’re still technically precise. However, the museum text claims misleadingly that Takahata directed Perrine; according to other sources, his credits were limited to storyboarding two of its 53 episodes, between his TV directing marathons on Heidi, Marco, Anne and the series version of Chie the Brat.

More helpfully, the text explains how Takahata worked to develop better processes in anime, developing a full-fledged layout system in the early 1970s. Layouts are drawings which bridge storyboards and animation, containing the information the animators need (positions of characters, direction on action, and so on). In particular, layouts make it possible to standardise quality over an epic-length anime series. Many of the layouts on display are drawn by Miyazaki, going back to the cheery Panda! Go Panda films with their obvious foreshadowings of Totoro and Ponyo.

The Panda and Heidi anime seem linked to the warmest memories in the exhibition. We hear a lovely story from Yoichi Kotabe, a frequent Takahata collaborator, about seeing children sing along to the Panda song even the first time they heard it; he was enormously moved. There’s also a charming video photo-montage of Takahata’s team visiting Switzerland to research Heidi – the photos include a few background locals who seemingly turn up in the series. That the exhibit includes a huge model “georama” of Heidi’s sweeping mountain suggests how fondly the series is recalled in Japan, nearly fifty years on.

Takahata’s anime has a different kind of emotional power by Grave of the Fireflies. There’s a telling quote from the author Akiyuki Nosaka, who wrote the source Grave book, which fictionalised his war experiences. Nosaka says that seeing even the sketches for the Grave film “made me look a little more honestly at my past, something I had avoided doing for so long.” One layout drawing, showing the boy Seita leaning over his stricken sister, has a breath-catching power in sketch form, tangibly greater than the equivalent animation cel, which is also displayed.

Takahata came to think much the same. Late in the exhibition, there’s a section on his friendship with the Canadian animator Frederic Back. A drawing from Back’s 1978 film Tout rien bears the inscription, “Pour Isao Takahata-san, avec ma profonde gratitude et mon amitié.” The museum text notes that Back’s animated style gives the impression of only drawing what the artist wants to draw. There are signs of this aesthetic in Takahata’s Only Yesterday, in the childhood scenes with their copious white spaces. But the idea is truly developed in Takahata’s last two features, Yamadas and Kaguya.

It’s easy for artists to praise each other’s work, as Takahata and Back do fulsomely. In similar vein, the exhibition includes a picture given Takahata by the Russian animator Yuri Norstein, showing Norstein’s Hedgehog in the Fog. There’s also a sizeable display for one of Takahata’s formative influences, Paul Grimault’s French animation The Shepherdess and the Sweep (later revised as The King and the Mockingbird, which is available on British DVD). In a video clip, Takahata says how he was given chills by the evil king’s habit of eliminating people by dropping them through trapdoors. He says Shepherdess made him want to create films with a “profound sense of character and humanity.”

But Takahata’s own humanity has come under scrutiny, given blunt comments made recently by Ghibli’s producer Toshio Suzuki. Takahata may have been warm towards fellow auteurs, but his treatment of his own staff is another matter. Suzuki claims that Takahata’s work demands traumatised the brilliant young artist Yoshifumi Kondo (who directed Ghibli’s Whisper of the Heart). Suzuki claimed that Takahata himself acknowledged some responsibility for Kondo’s tragically early death in 1998, aged 47.

Unsurprisingly, there’s no mention of Suzuki’s claims in the exhibit, although Kondo’s name looms large. His contributions to Anne are celebrated; he was largely responsible for realising the skinny, bulge-eyed little girl who grows up into a beautiful woman. Kondo’s work for Only Yesterday is also highlighted, with his painstaking sketches of the adult characters, trying to capture even the crease-lines of their laughs.

It’s impossible to dismiss Suzuki’s comments glibly. It is possible to wonder, though, if Kondo was as driven by his own compulsion for perfection as he was by the slavedriving demands of Takahata. Remember, it was after his onerous time with Takahata that Kondo took on directing Whisper; his last credit before his early death was as an animation director on Princess Mononoke, under Miyazaki.

It’s impossible to dismiss Suzuki’s comments glibly. It is possible to wonder, though, if Kondo was as driven by his own compulsion for perfection as he was by the slavedriving demands of Takahata. Remember, it was after his onerous time with Takahata that Kondo took on directing Whisper; his last credit before his early death was as an animation director on Princess Mononoke, under Miyazaki.

Many of Takahata’s other staff are given their due in the exhibition, such as the legendary background painter Kazuo Oga, as open to experiments with detail and minimalism as Takahata himself. Just compare Oga’s safflower field in Only Yesterday with the woods in Kaguya; both radiant, yet one is like a documentary, the other is like a picture book. Kauya animator Shinji Hashimoto is honoured for his visual coups in the film, such as the heroine dissolving into a vibrant scribbling dash, and later spinning ecstatically under a cherry tree. Both moments are broken down in the exhibit while losing none of their awe, letting you see the original drawings which comprised such wonders.

For the rest of this review, I’ll summarise highlights of the Japanese-language documents, kindly translated by Carlos. Many of them are in the exhibition’s first rooms, including notes Takahata wrote as producer on Miyazaki’s Nausicaa, about the film’s music. He said an “image song” to promote Nausicaa should have a historical, folk flavor with the scent of legend. Anyone who’s heard Nausicaa’s actual image song will be amused by that. Having recently directed the classically-inflected music film Gauche the Cellist, Takahata also envisioned an in-film score inspired by Richard Strauss’ Der Rosenkavalier and the work of Maurice Ravel – though the most obvious lift in Hisaishi’s final Nausicaa score is from West Side Story.

There are reams of documents relating to Little Norse Prince, where Takahata famously fought the Toei studio, which was trying to rein in the film’s budget. One of the best documents – handwritten in a notebook, apparently a draft for a letter – has Takahata railing against Toei’s demand that a spectacular scene, showing wolves attacking a village, should be reduced to a sequence of still pictures. Takahata acknowledged that this might be acceptable in a limited-animation film, but Prince’s existing scenes had all been fully, lushly animated (and still look amazing today). He argued that the switch to still pictures would throw viewers fatally out of the film, giving them an impression of half-finished cheapness. That time, Takahata lost; the scene was indeed done as still pictures.

But the most startling document is another one from the 1960s, where Takahata first considered the prospect of a Kaguya film. Toei was considering adapting the story; though planned as an animation, it would have been helmed by a feted live-action director, Tomu Uchida. The film was never made. But in a memo, the young Takahata sets out his thoughts on Kaguya, starting with his admission that he didn’t find the tale interesting, and was perplexed by it. There’s a long series of what read like excuses, reasons why Takahata couldn’t adapt Kaguya. Toshio Suzuki describes Takahata taking a similar tack on their very first encounter, when Takahata took an hour explaining why he couldn’t give an interview.

But the most startling document is another one from the 1960s, where Takahata first considered the prospect of a Kaguya film. Toei was considering adapting the story; though planned as an animation, it would have been helmed by a feted live-action director, Tomu Uchida. The film was never made. But in a memo, the young Takahata sets out his thoughts on Kaguya, starting with his admission that he didn’t find the tale interesting, and was perplexed by it. There’s a long series of what read like excuses, reasons why Takahata couldn’t adapt Kaguya. Toshio Suzuki describes Takahata taking a similar tack on their very first encounter, when Takahata took an hour explaining why he couldn’t give an interview.

Then Takahata gets to business. He throws out radical suggestions for a Kaguya film; looking to shadow animation, using anti-real, abstract characters, and eschewing first-person viewpoints, only showing characters from the side. (Already Takahata was leaning towards objectivity.) Then he suggests three possible treatments for Kaguya. One would be a satire, focusing on men’s desire for Kaguya, who Takahata suggest may not even need to appear in the film. Takahata takes that further, suggesting Kaguya’s desirability comes from the fact she does not exist. “Men surround her, make a silly dance.” Such a non-existent object of desire, Takahata says, would be a fine comment on the modern world.

One of Takahata’s other versions is a true love story, subverting the original tale where Kaguya’s suitors all fail. But Takahata also suggests an eye-opening alternate version which feels like a dark twist on the Pygmalion legend. This idea centres on Kaguya’s “father”; that is, the bamboo-cutter who discovers the magic girl. Kaguya is the most beautiful woman in the world, and her artist father realises he can never create anything to match her beauty. The knowledge maddens him. Loving and hating Kaguya, he can find only one way to unite with her, to close the gap. He stabs Kaguya with his cutting-knife, scarring her to inscribe his art on her beauty.

As she dies, Kaguya thanks him. Her celestial family forced her to come to this world, and now she can go home, through her father’s agony, his hate, his sin, his fire of life. The father declares he has created something that will endure forever; and now he is so tired. Then the worn-out artist dies, under the light of the moon.

Beneath, Takahata writes, perhaps regretfully, “This is not for animation.”

Addendum: Many of the exhibit’s materials are also presented in a gorgeous softcover tie-in artbook, also called Takahata Isao: A Legend in Japanese Animation, which weighs in at 250 A4-sized pages and includes two English-language essays. I couldn’t resist buying a copy in the museum gift store, while Carlos purchased a soft panda (from Panda! Go Panda!) for his daughter.

The Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo is near the Imperial Palace; the closest station is the Takebashi metro station on the Tozai line. Standard entrance is 1,500 yen. The exhibition is closed on Mondays, except for 15th July, 12th August, 16th September and 23rd September. It is open on other days from 10 a.m. except for the following days: 16th July, 13th August, 17th September and 24th September. The exhibition closes at 5 p.m. on Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Sunday. On Friday and Saturday it is open late to 9 p.m.

Leave a Reply