The Case of Hana & Alice

January 7, 2017 · 0 comments

By Jasper Sharp.  There was a time in the late-1990s when director Shunji Iwai possessed near celebrity status among young movie fans in Japan, the poster boy for a new breed of filmmaker who emerged neither from the moribund studio system, nor the uncompromisingly raw-edged counterculture of the 1980s independent scene, but from the image factory of television, advertising and music videos. Films such as his breakthrough feature Love Letter (1995) and Swallowtail Butterfly (1996), an ambitious, sprawling portrait of the denizens of a makeshift immigrant community situated on the outskirts of Tokyo, proved cult hits, pulling off the impressive feat of being popular yet populist. They showed that independent film didn’t have to be austere, confrontational and stylistically stripped-back. It could be slick, escapist and entertaining.

There was a time in the late-1990s when director Shunji Iwai possessed near celebrity status among young movie fans in Japan, the poster boy for a new breed of filmmaker who emerged neither from the moribund studio system, nor the uncompromisingly raw-edged counterculture of the 1980s independent scene, but from the image factory of television, advertising and music videos. Films such as his breakthrough feature Love Letter (1995) and Swallowtail Butterfly (1996), an ambitious, sprawling portrait of the denizens of a makeshift immigrant community situated on the outskirts of Tokyo, proved cult hits, pulling off the impressive feat of being popular yet populist. They showed that independent film didn’t have to be austere, confrontational and stylistically stripped-back. It could be slick, escapist and entertaining.

Looking at how much the Japanese movie culture has changed over the past few decades, Iwai can now be seen as something of a game changer. Key to his impact was his stance that the national cinema did not have to exist within the bubble of its own traditions, but within the whole gamut of the country’s multimedia culture, be it music, manga, TV drama or idol ‘gravure’ photo books. The flipside was that despite his popularity, Iwai was considered an outsider by the more staid forces within the industry he hoped to revolutionise, while his brand of uber-stylized pop-culture-savvy hipness proved an anathema to the critics and curators entrusted with manning the gates that granted Japanese films access to foreign audiences. By the time DVD, the internet and the proliferating specialist festival circuit saw a fresh wave of knowledge and appreciation for Japanese cinema break on Western shores, Iwai was already considered something of a flagging force. Since All About Lily Chou-Chou (2001) and Hana & Alice (2004), he’s barely caused a blip on Western radars, despite two fairly recent steps into English-language filmmaking with a segment in the anthology New York, I Love You (2008) and the US-Canada co-production Vampire (2011).

The UK Blu-ray release of The Case of Hana & Alice (2015), Iwai’s first foray into the anime field and a prequel to his 2004 live-action film, provides a good opportunity to reassess his cross-media endeavours during this seemingly fallow period. Japanese documentaries rarely cause much of a stir outside their home country, of course, especially when they’re celebrations of the nation’s cinematic heritage such as The Kon Ichikawa Story (2006), while his friends after 3.11 (2011) was one of many worthy titles lost in the tsunami of similarly-themed non-fictional mediations on the Fukushima incident and its aftermath. Nor have his films as a producer and screenwriter (usually hiding behind the pseudonym of Aminosan) on such titles as Rainbow Song (Naoto Kumazawa, 2006), The Bandage Club (Yukihiko Tsutsumi, 2007), Halfway (Eriko Kitagawa, 2009) and Bandage (2010), directed by Takeshi Kobayashi (the composer-music producer who scored a number of Iwai’s films), gained much traction on the international festival circuit, despite performing respectably enough at the local box office.

More interesting were Iwai’s earlier dabblings within Japan’s multimedia landscape, specifically with regards to the “new media” of the internet that seemed to offer limitless potential for building extended narrative worlds, stretching beyond traditional notions of the screen at the time All About Lily Chou-Chou was conceived. Prior to its production, Iwai launched a fan site dedicated to its fabricated eponymous J-pop idol, through which he solicited its members’ input to shape the screenwriting process. Its tale of the growing pains of small-town teens who escape into the cosy shared space of the fabricated pop phenomenon’s ‘Lilyphilia’ chatroom saw him moving from the more gentile whimsy of his earlier work into darker territory, though its scenes of delinquency and classroom humiliation didn’t seem to harm its domestic earnings and it remains one of his best-known films overseas.

More interesting were Iwai’s earlier dabblings within Japan’s multimedia landscape, specifically with regards to the “new media” of the internet that seemed to offer limitless potential for building extended narrative worlds, stretching beyond traditional notions of the screen at the time All About Lily Chou-Chou was conceived. Prior to its production, Iwai launched a fan site dedicated to its fabricated eponymous J-pop idol, through which he solicited its members’ input to shape the screenwriting process. Its tale of the growing pains of small-town teens who escape into the cosy shared space of the fabricated pop phenomenon’s ‘Lilyphilia’ chatroom saw him moving from the more gentile whimsy of his earlier work into darker territory, though its scenes of delinquency and classroom humiliation didn’t seem to harm its domestic earnings and it remains one of his best-known films overseas.

Hana & Alice owes its genesis to the internet, too, beginning life in 2003 as a four-part series of short online films financed by Nestlé, essentially as an extended commercial for Kit-Kat (you can find the episodes at the bottom of this page on the company’s Japanese website), which established the characters of the two high-school chums. Alas, the World Wide Web (as we used to call it) never proved quite as worldwide in its reach as its name promised, at least for those communicating in languages other than English. While the 2004 feature-length consolidation of the girls’ exploits became a big hit in Japan, we can partly attribute its relatively modest overseas profile to a lack of familiarity with the source stories – unlike the more challenging watch of Lily Chou-Chou, Iwai’s last fictional feature of note was never to get a release in the UK.

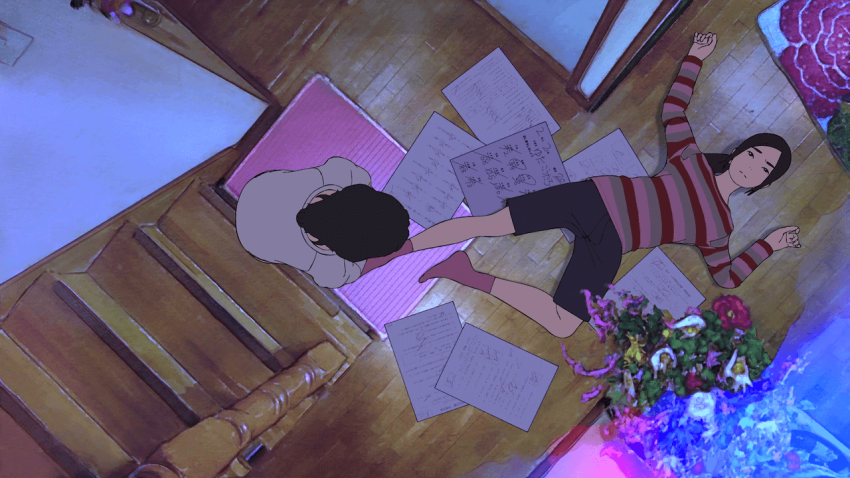

It makes sense that Iwai would choose anime as the medium through which to present this backstory behind the characters’ first encounter in The Case of Hana & Alice, its culture-crossing potential firmly established by the international successes of Studio Ghibli over the past 20 years. Indeed, Ghibli seems an apt yardstick by which to judge its wistful reverie of schoolyard nostalgia, with Iwai adhering closely to the studio’s classical 2D aesthetic. It also overcomes the problems inherent in bringing back the actresses cast as Hana and Alice a decade earlier, Anne Suzuki and Yu Aoi, both of have become major stars in Japan thanks to their role in the original (although Aoi actually made her debut in Lily Chou-Chou and Suzuki had been a child actor since the mid-1990s). Using rotoscoping, a technique whose potential Iwai became aware of while acting as the producer of Ryuhei Kitamura’s futuristic anime short Baton (2009), allowed the pair (now aged 29 and 31 respectively) to be recast as their 14-year-old incarnations. This method of drawing over live-action footage certainly has resulted in convincing stand-ins for their adolescent selves, retaining both their characteristic voices and body language, and doing a remarkable job of expressing the vulnerability and social awkwardness of young women exploring a new world of emotions.

While enjoyable as a self-contained work, for those not acquainted with the characters or their milieu, The Case of Hana & Alice comes across as a film of two tenuously related halves that opens with the arrival of bright young thing Tetsuko Arisugawa in a small-town backwater to start a new life with her recently separated mother. The early scenes detail Tetsuko’s struggles to settle into her new school, and into her new nickname of “Alice” ascribed to her by her classmates, abbreviated from the maiden name her mother has reverted to. Intrigues abound as she comes to terms with the pecking order of her peer group at Ishinomori Junior High, like what are the strange sigils chalked beneath the dusty desk she is assigned, and who is the strange hikikomori girl she first glimpses peering at her through her curtains of the “floral folly” of the house next door?

The latter aspect is a mystery easily solved by those who recognize the physiognomy or know the Japanese word for “flower” – hana. Less obvious is the background as to why Hana has withdrawn from school, a convoluted plot strand set in motion by a flashback from the school year prior to Alice’s arrival of one of the pupils leaping on to her chair mid-lesson and proclaiming “I am Judas of the Anaphylaxis!” as if in a state of demonic possession. Alice’s journey to the roots of the school’s self-created occult mythology, which saw the mysterious disappearance and rumoured death of two former students, eventually bring her face-to-face with her future soulmate, but there’s a lot going on this first half, possibly too much, and it is questionable how much in the expositional barrage is entirely relevant to the main thrust of the drama. Characters pop up provocatively at various points only to disappear with no further mention, like the girl called Fuko who recognises Alice from the ballet lessons they both attended at some earlier point in their childhood. Alice’s balletic prowess, realised as impressive line-drawn sketches of her exuberant pirouettes around the empty, unfurnished space of her new home, was a major component of her earlier live-action excursions, but plays little role here other than to showcase the convincing body language permitted by the rotoscoping method.

The latter aspect is a mystery easily solved by those who recognize the physiognomy or know the Japanese word for “flower” – hana. Less obvious is the background as to why Hana has withdrawn from school, a convoluted plot strand set in motion by a flashback from the school year prior to Alice’s arrival of one of the pupils leaping on to her chair mid-lesson and proclaiming “I am Judas of the Anaphylaxis!” as if in a state of demonic possession. Alice’s journey to the roots of the school’s self-created occult mythology, which saw the mysterious disappearance and rumoured death of two former students, eventually bring her face-to-face with her future soulmate, but there’s a lot going on this first half, possibly too much, and it is questionable how much in the expositional barrage is entirely relevant to the main thrust of the drama. Characters pop up provocatively at various points only to disappear with no further mention, like the girl called Fuko who recognises Alice from the ballet lessons they both attended at some earlier point in their childhood. Alice’s balletic prowess, realised as impressive line-drawn sketches of her exuberant pirouettes around the empty, unfurnished space of her new home, was a major component of her earlier live-action excursions, but plays little role here other than to showcase the convincing body language permitted by the rotoscoping method.

But about halfway through, The Case of Hana & Alice meshes into a more satisfactory narrative entirely, when it becomes clear that Hana knows the true story behind the mystery and attempts to steer her new friend towards its source (without giving too much away, it is worth pointing out that the original title translates as “The Murder Case of Hana & Alice”, and that the Judas is pronounced “Yuda”, a common enough surname in Japan). Mistaken identities, failing phone batteries and an escalating series of white lies inform the duos’ subsequent explorations across a series of vividly rendered urban locales, the background artwork recalling the hyper-realised backdrops of the Ghibli’s works more rooted in the real world, such as Ocean Waves (1993), Whisper of the Heart (1995) or From Up on Poppy Hill (2011), so rich in detail one can read the number plates of passing cars or the logos of cans stacked in vending machines (and indeed, Kit-Kat wrappers).

As a standalone piece, The Case of Hana & Alice possesses a similarly ambling, circumlocutory approach as much of Iwai’s live-action work, a shaggy-dog story which opens a window onto the same world of rite-of-passage girlhood as depicted ten years ago, but for a fresh generation. But its strengths are in its individual moments of charm, of tenderness, of humour, and of friendship, and with a manga serialisation published to coincided with the film’s release in Japan, one suspects the tales of Hana and Alice aren’t over yet. And with his critically-regarded return to live-action this year with The Bride of Rip Van Winkle, it seems like Iwai, too, is now firmly back on the map.

The Case of Hana & Alice is released in the UK by Anime Limited.

Leave a Reply