The Deer King

July 17, 2022 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

Supposedly, life has returned to normal in the lands of Aquafa, but there are still unwelcome echoes of the past. The Empire of Zol maintains garrisons of soldiers on Aquafan territory, and plunders the nation’s riches for its own ends. But a new threat arises, fighting the Zolians on an unexpected front. Long believed dormant, the dreaded mittsual plague is about to resurge in another wave.

Mittsual, or Black Wolf Fever, is a deadly affliction passed on by canines. In Masashi Ando and Masayuki Miyaji’s anime feature The Deer King, it is presented as something that is both magical and physical, a rising storm of black vapours that cloaks an onrush of rabid dogs. For two generations, it has broken out in repeated waves, leading to swift but largely palliative advances in medical knowledge among Zolian doctors. We see them at work, masked up and socially distanced, among the mass funeral pyres of a salt mine, where a mittsual outbreak has killed workers and guards alike.

Entirely? No, not entirely. Someone has made it out alive, and in an impressive series of deductions like something out of Black Death CSI, Sae the tracker works out that it was a prisoner, who broke out of his cell and somehow clambered to freedom, despite suffering from an animal bite. A man is on the run, and if he is asymptomatic, his blood might form the basis for the long-hoped-for mittsual vaccine… all they have to do is find him.

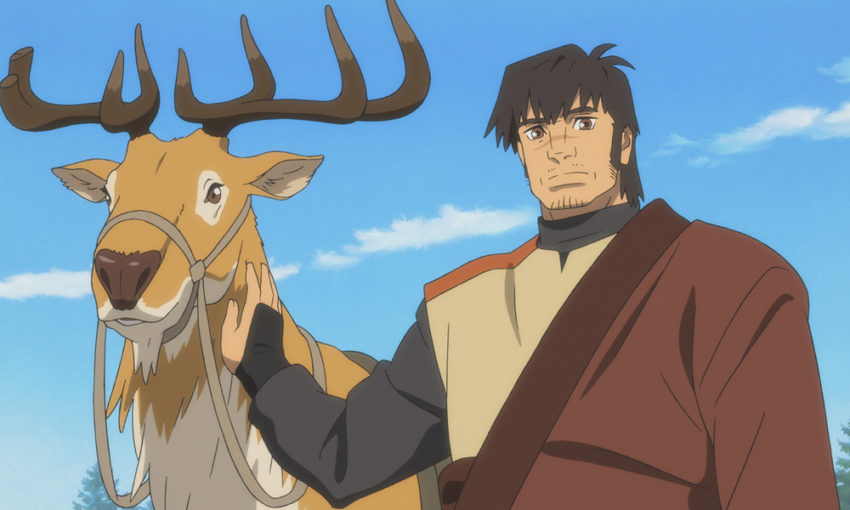

The fugitive is ultimately revealed as Van Gamsa, a celebrated war hero who has spent the last few years as a nameless slave in the salt mines. Unaware that he is a marked man, hunted by both sides in an as-yet undeclared resumption of hostilities, he drifts among the reindeer herders on Aquafa’s borderlands. His sojourn there is a remarkable change of place – a slice-of-life glimpse of a yurt-dwelling tribe that mixes elements of the real-world Mongols and the Siberian Evenki, bewitching the viewer with an interlude that waves away the plot awhile, until Van’s hunters catch up with him.

To say that Production I.G’s anime has caught the spirit of the age is something of an understatement. It mixes a milieu like something out of Game of Thrones, with a woke sensibility that mirrors Mari Okada’s Maquia, and, of course, a pandemic. Nahoko Uehashi’s original 2014 fantasy novel won a Japanese prize for medical fiction, and this film adaptation retains much of her interests in the way a pre-modern culture faces a disease it doesn’t understand. In her original, mittsual was not the only disease faced by the characters, who struggled with medieval solutions to medical problems. Made during the COVID-19 outbreak that did for the 2020 Olympics and turned everybody into lockdown loonies, this adaptation is thick with imagery and ideas that have taken on a new resonance during our own plague years, including fantasy-era PPE, religious anti-vaxxers, herd immunity (at least the people of Aquafa have something to smile about), and pandemic-derived racism.

The story is loaded with moments of grim, visual gallows humour, including a lovingly delivered bowl of prison gruel that is upended before Van can reach it, or a dead body plummeting down from above when Van experimentally tugs at a rope ladder. A wild boar, thought to be dead, gives one last death-rattle sigh, spooking the hunters around it. Taking a hint from George R. R. Martin, Deer King also has a sardonic attitude towards some of the tropes of high fantasy, such as the gruff bodyguard Makokan, whose shouty temper has to be repeatedly reined in by his soft-spoken master Hohsalle.

The credits include a thank-you to the Seurasaari Open-Air Museum in Helsinki, Finland, a rustic recreation of old-time Nordic living that has informed much of the depiction of the Aquafa villages and farms. This, it seems, was a production decision that went above and beyond the world-building choices in Uehashi’s original novel — I checked with Mikko Teräsvirta, the intendant at the museum, and he recalled that the production team’s visit was long, long ago, in 2016 pre-COVID times. However, not every aspect of the design has relied quite so much on real-world materials. The nomads’ tents are revealed to be tent-like structures draped over stone, evoking the way they look today in modern Chinese theme parks, where such perma-yurts are commonplace. But Ando reports this as a deliberate design decision, to demonstrate how the former nomads have adapted to a more sedentary existence, retaining the tents as symbols of their old wandering lifestyle, but now as coverings over immovable stone.

Scenes also come dripping with symbols of oppression and enslavement, including a memorable moment when Van is caught between a rock and a hard place, his arm locked in the jaws of a savage wolf, but still chained to the wall by an iron collar that threatens to strangle him. Such moments reflect recurring concerns in many of the books of novelist Uehashi, a professor of ethnology, who wrote her doctoral thesis on the integration, or lack thereof, of Australian Yamatji aborigines. From her early novels such as Moribito: Guardian of the Spirit and The Sacred Tree, Uehashi has returned time and again to the idea of the lost knowledge of a conquered people, and of the tensions between colonisers and colonised. In both her fiction and her academic work, she also shows an incredible enthusiasm for unusual, tribal-influenced forms of story-telling, and a respect for pre-modern beliefs. For Uehashi, “magic” and “superstition” are not laughable delusions, but earnest attempts by our ancestors to impose some sort of system on the world, sometimes imperfectly, sometimes with inspiring results.

Throughout Deer King there are subtle hints of a nation under occupation, hand signals and glances between people who secretly share religious beliefs or memories of military service. The people of Aquafa struggle to keep their smiles pasted on, while their Zol masters pretend they’re all friends again. The turbanned Zol occupiers are breezy and off-hand about how great it is the war is over, but still sneeringly resentful of the “Curse of Aquafa”, an epidemic that Zol unleashed on itself by invading in the first place! Just to make power relationships abundantly clear, the Zolian viceroy Utalu orders the Aquafan vizier Tohlim to literally lick his wounds, proffering a gangrenous leg in need of a wash. The fact that Tohlim is ready to do so points to a crucial, game-changing issue that the Zolians are perpetually jumpy about: mittsual doesn’t seem to affect them.

But the Aquafans are up to something. Despite his proclamations of loyalty and surrender, the collaborating King of Aquafa is also the leader of the resistance. He is secretly behind both of the recent mittsual outbreaks – a dog attack on a falconry expedition that has left the viceroy Utalu gravely wounded, and the catastrophe at the salt mine. Confident that mittsual will only afflict Zolians, he is ready to attempt a low-tech form of bacteriological warfare… except now his most decorated war-hero risks ruining his plan by becoming the one-man cure-all. A chess-player through-and-through, the King is ready to sacrifice a single knight for the greater good of his kingdom.

Meanwhile, Van fights demons of his own, haunted by memories of the wife and son he left behind to fight the Zolians, who died while he was away – shades here of the hallucinatory flashbacks of Ridley Scott’s Gladiator. He has also acquired a surrogate daughter, Yuna, a girl he rescued from the salt mines, a gap-toothed infant who fixates on Van as her new father. In a mirror of the legendary “deer king”, a stag that Van once saw defending a fawn from wolves, Van similarly bonds with Yuna, his instinct to protect her both bringing him not only purpose but also fresh nightmares of failing once more. When Yuna is inevitably taken from him, his dogged pursuit of her is heroic and tragic. Badly wounded and barely conscious, he struggles to put one step in front of the other, limping hopelessly after her sprinting kidnappers.

That takes us to the end of the first volume of Uehashi’s original books, and the mid-point of the film. Van has acquired two unlikely travelling companions, each of them after his blood in their own way. Hohsalle is a doctor who has worked out that today’s mittsual is a new strain (the COVID-delta of its day) that might also prove deathly to the people of Aquafa. His mission is to find a cure for everyone, for which he needs to keep Van alive. But the two men are stuck on the road with Sae, the tough Aquafa huntress whose mission is to kill Van before his blood can be used to defeat the disease. With religious fanaticism, she clings to the idea that the plague is a divine punishment that can only affect Zolians, which means Hohsalle has to somehow persuade her not to stab Van in the back.

It’s a beautiful stand-off. Van needs Sae to track the missing Yuna, and Hohsalle to keep him alive, both Hohsalle and Sae need Van for mutually exclusive ends. The fate of two kingdoms hangs in the balance, as if all the King’s chess pieces are in play, and each threatens the other. And in a metaphor that will play out at a much more magical level later in the story, Van is a “chosen one” for two rival powers, who must decide which side best deserves his service and his loyalty.

I would also recommend that you stay for the post-credits sequence, although that is something of a misnomer here, because the animation continues, unbroken, throughout the credits in a prolonged Ghibli-style coda, showing the fates of numerous characters over the next few years.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History. The Deer King is released in UK cinemas on 27th July.

cinema, Deer King, Japan, Jonathan Clements, Masashi Ando, Masayuki Miyaji, Production I.G

Leave a Reply