Ping Pong

October 16, 2015 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

“I want to see more relaxed animation coming from Japan,” Ping Pong director Masaaki Yuasa told twitch.com. “Animation where everything is not so perfectly drawn. The strict way it looks now, it sometimes seems like working on anime is more pain than pleasure! I prefer to have joy in making animation.”

“I want to see more relaxed animation coming from Japan,” Ping Pong director Masaaki Yuasa told twitch.com. “Animation where everything is not so perfectly drawn. The strict way it looks now, it sometimes seems like working on anime is more pain than pleasure! I prefer to have joy in making animation.”

Ping Pong features a maverick, joyous table tennis player, as depicted by a maverick, joyous anime director. Masaaki Yuasa has had followers for the last decade now, though many fans don’t know his name. But even in mainstream animation, you may have seen his hyper-inventive work. Recently, he directed an episode of Space Dandy’s second season (“Slow and Steady Wins the Race, Baby”) in which the title character meets a lovelorn talking fish… and you have no idea how odd that looks till you see it animated.

Last year, Yuasa guest-directed an episode of the American cartoon Adventure Time (“Food Chain”); he also got attention as director of the twelve-minute Kick-Heart, the first crowdfunded studio anime. But these gigs came from a reputation that Yuasa had built with his earlier anime, despite their patchy distribution. You might have caught a cinema screening of his extraordinary feature Mind Game (2004), in which the protagonist is killed by yakuza, swallowed by a whale… and that’s the start of his adventures. In my book 100 Animated Feature Films, I called Mind Game “spectacular, spontaneous, confusing, kooky and hilarious… an anti-realist bricolage.”

A freelancer, Yuasa has moved around. Mind Game was made at Studio 4 Degrees C (for which Yuasa also directed a segment of the anthology Genius Party). His first three TV shows were made at Madhouse; only one, The Tatami Galaxy, has been released in Britain. It’s a comedy of university life, with a science-fiction twist that gets very Douglas Adams. Kick-Heart was made with Production I.G, while Ping Pong is with Tatsunoko, which is moving in trippy ways; witness Gatchaman Crowds, or “G-Force in the Sky with Diamonds.”

A freelancer, Yuasa has moved around. Mind Game was made at Studio 4 Degrees C (for which Yuasa also directed a segment of the anthology Genius Party). His first three TV shows were made at Madhouse; only one, The Tatami Galaxy, has been released in Britain. It’s a comedy of university life, with a science-fiction twist that gets very Douglas Adams. Kick-Heart was made with Production I.G, while Ping Pong is with Tatsunoko, which is moving in trippy ways; witness Gatchaman Crowds, or “G-Force in the Sky with Diamonds.”

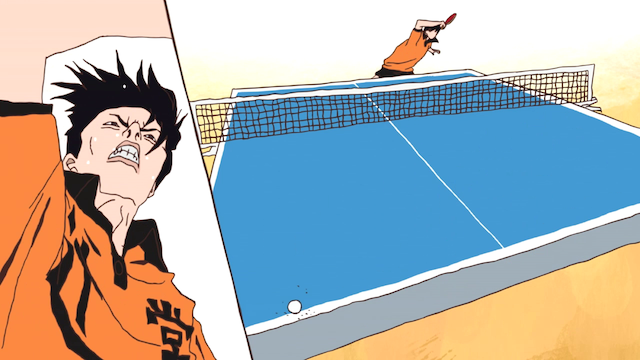

But wherever Yuasa goes, he’s as distinctive as any of the great indy world animators, like Britain’s Nick Park (Yuasa loves The Wrong Trousers) or America’s Bill Plympton (who called Mind Game, “the Citizen Kane of animation). Yuasa loves interesting-looking, non-generic graphics, freed of the tyranny of Cute and stripped to a few infirm lines for easy use. Perhaps even more, he loves moving those graphics in idiosyncratic ways to suggest the artist’s hand as strongly as King Kong’s bristling in stop-motion. To the non-animator, Ping Pong looks very hand-drawn; like Ghibli’s Ponyo, it’s averse to smoothness and straightness. In fact, a promo video for Ping Pong showed how the series was made with Flash Animation, developing its own digital techniques “to get slow movements, turning and big zooms.”

It’s always tempting to write about such animators as if they’re one-man bands. Yuasa’s team deserves recognition, including his ever-present female collaborator Eunyoung Choi, who directed the spectacular penultimate episode of Ping Pong (Yuasa did the crazily dense finale himself). Choi also directed a Space Dandy episode, a Fantastic Planet-esque story with sentient plants, “Plants are Living Things Too, Baby.” Yuasa’s other regular collaborators include Nobuta Ito, who has character design and animation director credits on Ping Pong and Yuasa’s other anime. There’s a celeb guest appearance from mad animator Shinya Ohira, who has credits on many anime (we mentioned him in connection with A Letter to Momo). His free-hand sensibility is such an obvious match for Yuasa’s that it’s strange they don’t seem to have collaborated before Ping Pong (they’ve since worked together on the Space Dandy fish episode). Ohira served up Ping Pong’s opening credits.

“In Japanese animation there are a lot of technical professions… Specialists with great technical skills in their own area,” Yuasa told twitch.com. “That can be both a good thing and a bad thing. Because often when someone is really good at what he’s doing, he keeps being asked to do the same again and again. And in Japanese animation I see so many people now doing similar things… I hope they will do new things. So much animation is mainstream, while I’d like more to be interesting.”

“In Japanese animation there are a lot of technical professions… Specialists with great technical skills in their own area,” Yuasa told twitch.com. “That can be both a good thing and a bad thing. Because often when someone is really good at what he’s doing, he keeps being asked to do the same again and again. And in Japanese animation I see so many people now doing similar things… I hope they will do new things. So much animation is mainstream, while I’d like more to be interesting.”

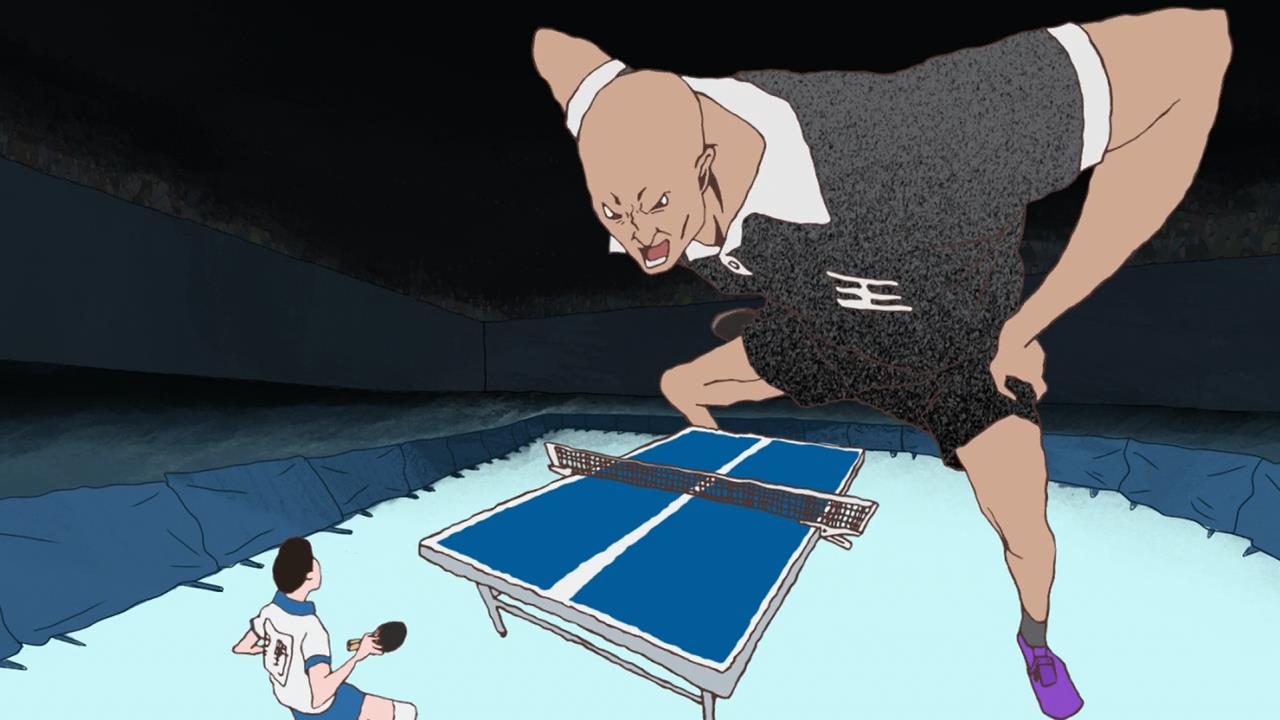

On a formal level, Ping Pong is full of multiple split screens, often turning the image into crazy pavings of comic-strip panels opening one by one; it’s another illusion of motion that doesn’t hide its trick. Ang Lee tried a similar effect in his live-action Hulk, but audiences didn’t go for it; more broadly, Ping Pong echoes the aggressively stylised visuals in the 1979 anime classic Rose of Versailles. And there’s a long tradition of manga and anime transforming sports through outrageous visual metaphors and distortions to make Matrix look tame.

It goes back to the first anime sports saga, the 1968 baseball show Star of the Giants, when one throw of the ball took a whole episode. As the Anime Encyclopedia puts it, the episode in question “darts from participant to participant, zooming in on their physical states and the internal monologues, freeze-framing moments of stellar action, and digressing into flashbacks and internal representations of their states of mind.” All these tricks are upheld by Ping Pong, Yuasa’s indie sensibilities meshing with a decades-old genre.

The story is equally traditional, and very good. Ping Pong may reflect a significant development for Yuasa simply in being a solid genre story, with none of the other-worldly gandering of Mind Game or his other works. Ping Pong is based on a manga (quite short by sports standards) by Taiyo Matsumoto, best-known for Tekkonkinkreet. Before the anime, Ping Pong was already turned into an entertaining live-action film by Fumihiko Sori, using extensive Matrix digital effects. Sori later directed the CG animated Vexille.

In all its versions, Ping Pong is set in a hyper-exaggerated world; as in many sports anime, its cosmos revolves round the sport. For instance, there’s a vision of an academy that devotes more effort into creating ping pong stars than governments spend on waging war. And yet, it’s also a hugely engaging, touching drama, revolving round two boys and a great many support players, any of whom could have been highlighted as the hero – and effectively they all are.

In all its versions, Ping Pong is set in a hyper-exaggerated world; as in many sports anime, its cosmos revolves round the sport. For instance, there’s a vision of an academy that devotes more effort into creating ping pong stars than governments spend on waging war. And yet, it’s also a hugely engaging, touching drama, revolving round two boys and a great many support players, any of whom could have been highlighted as the hero – and effectively they all are.

The pint-sized Peco is the most naturally joyous player, a ping pong idiot savant whose bragging and swaggering – not to mention his gourmet obsession with sweets – haven’t changed since elementary school. He forms an odd couple with the taciturn, sombre boy Tsukimoto, whose nickname “Smile” seems ironic – he never does. (Yuasa seems drawn to such hollow male protagonists; there are others in Mind Game and Tatami Galaxy.) The nature of their friendship is explored through the story, starting when Peco is taken down a clothes-line of pegs; he plays a game with Kong, an exiled Chinese champion, and is demolished.

From then on, it seems that Tsukimoto, not Peco is destined for greatness, if he can only start caring about winning. An untrained spirit and a spiritless technique; can either prevail in the fierce world of Ping Pong? Meanwhile, the boy’s foes prepare to fight for their own reasons, some bound up traumatically with parents living or dead. Midway through the series (part 6), there’s an exquisite downtime sequence at Christmas, showing what the players are doing or failing to do, accompanied by a plaintive karaoke song by Kong. It rivals Tokyo Godfathers for Yuletide tenderness.

Most of the characters are male, but special mention should go to the old woman at a ping-pong dojo, part of an elaborate backstory of a past generation of champion. Her wonderful rasp-edged voice is by septuagenarian voice-actress Masako Nozawa, who’s just reprised her decades-old roles as Son Goku and Son Gohan in Dragon Ball Z: Resurrection ‘F’: indeed, she’s voiced father and son through the whole Dragon Ball franchise. As with another of her characters, Doctor Kureha in One Piece, Ping Pong gives her the chance to act her age. Another note; both Kong and his coach, who speak mostly in subtitled Mandarin, are voiced in the Japanese version by ethnic Chinese actors, Yosei Bun and Tei Ha.

Ping Pong often enters Zen dimensions of higher consciousness that open only to sports champions; the last episodes suggest 2001’s Stargate or the graphically frenzied exertions of the final race in Mind Game. But the show is also grounded by real-world scenery. Most of it is set on or around Enoshima, a beautiful offshore island not far from Tokyo – Peco and Tsukimoto use the coastal “Enoden railway.” The same setting was used in the oddball anime Tsuritama, about aliens and fish. In one episode, Tsukimoto and his brutal-genial coach visit an amusement park; this is Yomiuriland near Tokyo, with a bone-rattling rollercoaster. But from the way Yuasa presents ping-pong, all you need for a rush is a bat, a ball and a table…

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films. Ping Pong will be released in the UK by Anime Ltd.

Leave a Reply