Books: Studio Ghibli

February 26, 2023 · 2 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

Producer Toshio Suzuki was entertainingly underwhelmed when he was approached by agents for the pop stars Chage and Aska, who asked if Studio Ghibli would do the video for their new single “On Your Mark.” Fact is, he said, he’d never heard of them.

Later versions of the story have tried to be a bit more upbeat. No; Ghibli was enthusiastic about working with those great artistes. Oh yes, everybody was super-stoked about it. What an honour it was. Then again, while Chage and Aska sold millions of records in Japan, if a foreigner has heard of them today, it’s usually because of Hayao Miyazaki’s “On Your Mark” video, which played in cinemas as a short accompaniment to Ghibli’s Whisper of the Heart movie. Well, at least until Aska (real name: Shigeaki Miyazaki, but no relation!) got busted for drugs possession, at which point Disney got cold feet about including the video in their “complete Miyazaki” collection, and withdrew it for a couple of years.

As Rayna Denison‘s new book, Studio Ghibli: An Industrial History, outlines, there are all sorts of assumptions made by commentators on Studio Ghibli’s work, including the one that Hayao Miyazaki is the be-all and end-all of its output. A cynic might even argue that “On Your Mark” was only on the bill in Japanese cinemas in the first place so that advertisers could throw around the word Miyazaki with impunity, even though it was a mere amuse-bouche for the main feature Whisper of the Heart, directed by Miyazaki’s protégé, Yoshifumi Kondo. The belief that Ghibli=Miyazaki, while it certainly has its semantic uses, is also an idea imposed in hindsight, because of how famous Miyazaki would become.

In a counterpoint to the media’s understandable obsession with the blockbusting Ghibli, the scholar Minori Ishida has argued for a consideration of the “diversity of anime production.” She points out that picking over the works of a single company can lead many researchers to assume that one particular studio’s practices and attitudes represent those of the entire Japanese animation medium. But as Denison ably demonstrates here, even the Ghibli archive contains multitudes, many of which have been shunted into the shadows by the overwhelming narrative of one Oscar-winning movie auteur.

Denison devotes entire sections to Ghibli’s short films and advertising contracts, many of which will be completely new to some self-proclaimed fans, despite a cumulative running-time equivalent to that of a whole other movie. These include, for example, Hayao Miyazaki’s nostalgic advert for House Foods (pictured), made in 2003 and unseen abroad.

There is a whole chapter on Ghibli’s position in the evolution of computer graphics, and another that draws on the rich and varied material by women working at Ghibli, noting that some female voices have been celebrated and promoted, while others have been roundly ignored. These include the colour designer Michiyo Yasuda (1939-2016), who is hardly unknown to Ghibli aficionados, but who was once regarded as so crucial to the look and feel of Ghibli films that Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata, up against it on the twin productions of My Neighbour Totoro and Grave of the the Fireflies, got into a tug-of-war about who could have her. Refashioning some her academic journal work, Denison also dedicates an entire chapter to the Ghibli Museum, which has successfully generated a modest movie’s worth of revenue every year for the last decade.

Some of Denison’s most crucial material is in her opening chapter, an account of the founding of Ghibli that questions many of the most popular myths spread by fandom and in the company’s own publicity. Denison indicates several figures who loomed in the studio’s early publicity even larger than Miyazaki and Takahata themselves. These include Yasuyoshi Tokuma (1925-2000), the company chief who was so colourfully celebrated in Steve Alpert‘s Ghibli memoir, Hideo Ogata (1935-2007), the founding editor of Animage, and Toru Hara (1935-2021), once Toei’s head of foreign subcontracting jobs, later the show-runner at Top Craft, the studio that formed the seed base not only for Ghibli, but for Pacific Animation Corp, later known as Walt Disney Studios Japan.

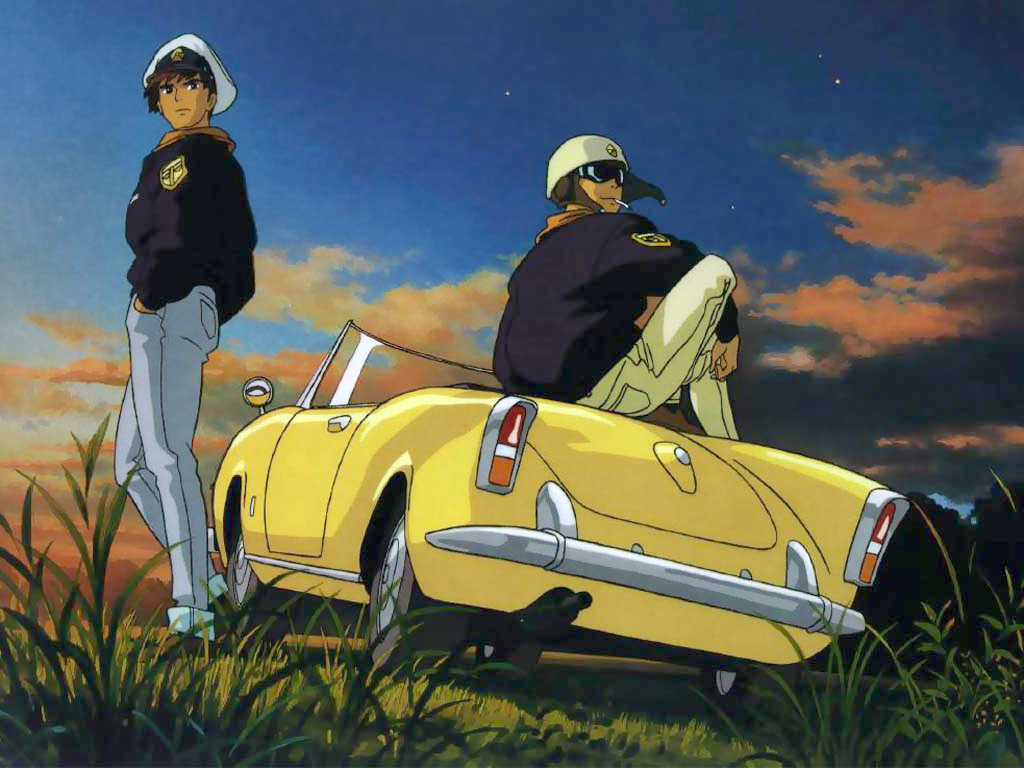

Denison’s closing chapters chronicle the studio’s management of its own legacy, particularly the revolving door of potential successors who were dragged in, put to work and booted out as the Ghibli top brass struggled to replicate Miyazaki’s world-beating success. She delves into what happens when the legacy of a creative artist is left in the hands of a committee of business interests, and the bizarre nepo-baby jiggery-pokery that propelled Goro Miyazaki, a landscape gardener who happened to be Hayao Miyazaki’s son, into a directorial position on Tales From Earthsea. She also devotes a section to the career of Hiromasa Yonebayashi, the unsung hero who carried the can for Ghibli during the early 2010s, and ends with a chapter about Ghibli’s influence on Ni no Kuni (pictured), a computer game franchise with Ghibli connections overlooked by many a film critic.

Less obviously, she also establishes the parameters and methodologies that other researchers might like to try for similar investigations of other studios – Tatsunoko, or OLM, or Madhouse, or Production I.G… Marie Pruvost-Delaspre has already done something similar with her excellent history of early Toei, but anime studies is crying out for industrial accounts of other players in the field, and while Ghibli might be the obvious starting point for publishers, authors and readers, Denison’s book will set a standard for many years to come.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History. Rayna Denison’s Studio Ghibli: An Industrial History is published by Palgrave Macmillan.

James Spearing

March 7, 2023 7:35 pm

Great review ( as always ). Is there a reason for the relatively high price? Looks great though.

Jonathan Clements

March 8, 2023 4:32 am

The matter of academic pricing is something that I have moaned about on several occasions in this blog, most notably here: http://blog.alltheanime.com/books-animation-in-china/ It can be very frustrating, not only to readers, but also to authors, that academic publishers assume that their books will only find an audience of a few hundred librarians, and must be priced accordingly. Usually, of course, they are right, but it's a career-risking gamble for an editor to buck that system on behalf of any one book. With any luck, the price point of Denison's book will drop both on Kindle and on a notional paperback in the future, but plainly someone at Palgrave Macmillan thinks it needs to earn its keep from the libraries first. It is all the more baffling when you realise that Palgrave Macmillan were the original publishers of my own Anime: History, which was priced at a very affordable £25, and consequently sold very well, not only libraries but to students. I wouldn't expect them to use that knowledge as carte blanche to rush every anime-related book into paperback, but something about Ghibli will surely find a larger market than, say, something about Mitsuyo Seo.