Early Korean Cinema

February 4, 2019 · 0 comments

by Jeremy Clarke.

This month, BFI Southbank and the Korean Cultural Centre UK are mounting a season of films from Korea made up to and including 1946 under the moniker Early Korean Cinema: Lost Films From The Japanese Occupation Period. The season is curated by KCCUK’s Hyun Jin Cho and University of Sheffield’s Kate Taylor-Jones.

This month, BFI Southbank and the Korean Cultural Centre UK are mounting a season of films from Korea made up to and including 1946 under the moniker Early Korean Cinema: Lost Films From The Japanese Occupation Period. The season is curated by KCCUK’s Hyun Jin Cho and University of Sheffield’s Kate Taylor-Jones.

A decade or so ago, such a programme would have been unthinkable: as Darcy Paquet wrote in 2007, at that time it was believed that no prints of complete Korean feature films from before 1945 had survived to the present day. However a number of prints have since come to light and are all being shown in the current season. They include romances and propaganda films.

Korea was a Japanese protectorate from 1905. It came under direct Japanese control from 1910 until Japan’s defeat by the Allies in 1945. For the first decade Korea was under repressive Japanese military rule in marked contrast to the liberalisation happening in Japan itself in the Taisho era (1912-26). This is not to say that there was no Korean resistance movement against the Japanese authorities in that period as is evident from comparatively recent South Korean blockbusters like The Age Of Shadows (2016). However with Japan’s increasing militarism from the 1920s, and its incursions into China from the 1930s, repression reasserted itself in Korea.

Just as Japan had pursued an intense period of modernisation since the 1868 Meiji Restoration, so its period of rule in Korea was marked by industrialisation and improvements in infrastructure. However, Japan’s relationship to Korea was not a particularly benevolent one, largely benefiting the Japanese at the expense of the indigenous population.

By the early 1930s, more than half of Korea’s arable land was in Japanese hands. Many Korean men were conscripted either into the Imperial Army to fight Japan’s wars or from 1939 as involuntary labour on the Japanese mainland, while women ostensibly taken for labour were actually used as “comfort women” (sexual slaves to service Japanese troops). But you wouldn’t find out much of the above from looking at Korean films from the period. Most of these issues are conspicuous by their absence.

Korea became a test-bed for the new-fangled technology of animation in Japan, when the director Sanae Yamamoto made The Mail’s Journey (1924), a public information cartoon for the Governor-General’s office. But the earliest known surviving Korean film is the silent Crossroads of Youth (Ahn Jong-hwa, 1934) described in the season’s press blurb as “a tale of love, desire, betrayal and revenge on the streets of Seoul.” Notably, it is being screened at the BFI Southbank this Thursday in “an experience comparable to what Korean audiences saw and heard when it first premiered,” not “silent” at all, but with live musical accompaniment, a narrator and onstage actors providing the voices. Sound film arrived in Korea in 1935, eight years behind Hollywood’s first ‘talkie’ The Jazz Singer (1927) and only a couple of years ahead of the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937.

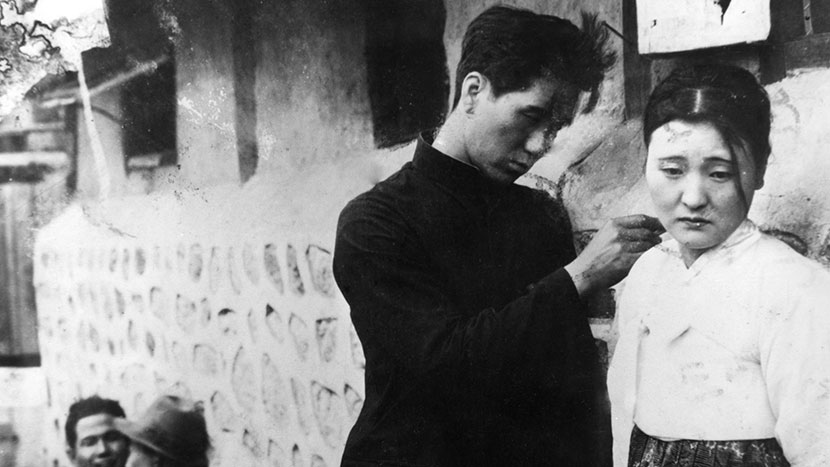

The vast majority of surviving films come from the subsequent period between that year and Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, which brought America into the war in 1941, although a couple of ten-minute, Japanese language newsreels survive from 1943. So too does the post-war feature Hurrah! For Freedom (pictured, Choi In-gyu, 1946) made after the Japanese were thrown out of Korea by the Allies and detailing the resistance against the former during World War 2. Director Choi previously made propaganda films like Tuition (1940).

The vast majority of surviving films come from the subsequent period between that year and Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, which brought America into the war in 1941, although a couple of ten-minute, Japanese language newsreels survive from 1943. So too does the post-war feature Hurrah! For Freedom (pictured, Choi In-gyu, 1946) made after the Japanese were thrown out of Korea by the Allies and detailing the resistance against the former during World War 2. Director Choi previously made propaganda films like Tuition (1940).

Starting off with an image of a caged pet bird, Sweet Dream (pictured below, Yang Ju-nam, 1936) casts Moon Ye-bong as neglectful wife and mother Ae-soon who goes to Seoul on a shopping spree and gets picked up by a man with whom she embarks on an affair. Much is made of the effect on her distressed daughter of her mother’s absence and the increasing tension between Ae-soon and her cuckolded husband. This film is just as interested in showcasing Seoul’s developing and thriving metropolis, with its department stores, theatre shows, hotel rooms and taxis, as it is in delivering its narrative.

That fascination is not shared by another story about women going to the capital Fisherman’s Fire (Ahn Chul-yeong, 1938). Ok-boon (Jeon Hyo-bong) the friend of the innocent In-soon (Park Rho-kyeong) has left their fishing village for Seoul and a job. In-soon’s father’s fishing business is deeply in debt, so In-soon wants to join Ok-boon in Seoul as soon as possible to earn some money. Her parents forbid her, not least because of local rumours that girls who go there end up in prostitution. When In-soon overhears in a conversation that she herself could be used as repayment for her father’s debt, she takes off for Seoul anyway. There she immediately falls into the hands of sexual predator Cheol-soo (Na Woong). When she later escapes his clutches, her parents’ previously expressed fears are realised.

Aside from the word ‘geisha’ being misused in the restoration’s English subtitles to describe the heroine’s eventual fate, any reference to Japan is as conspicuously absent from Fisherman’s Fire as it was from Sweet Dream. This may be down to both pressures of state censorship and a desire to portray a fantasy Korea free of the Japanese, in much the same way that numerous Hong Kong movies from the 1970s onwards largely airbrushed the British colonial presence out as if it had simply never been there.

Aside from the word ‘geisha’ being misused in the restoration’s English subtitles to describe the heroine’s eventual fate, any reference to Japan is as conspicuously absent from Fisherman’s Fire as it was from Sweet Dream. This may be down to both pressures of state censorship and a desire to portray a fantasy Korea free of the Japanese, in much the same way that numerous Hong Kong movies from the 1970s onwards largely airbrushed the British colonial presence out as if it had simply never been there.

Tuition (Choi In-gyu and Bang Han-joon,1940) sees eleven-year-old student Young-dal (Jeong Chang-jo) attend a school where his teacher Mr Tashiro (Kenji Susukida) is Japanese and speaks no Korean. This element at least is historically accurate in terms of Koreans being required to speak and write Japanese for official and bureaucratic purposes. Young-dal lives at home with his grandmother (Bok Hae-suk) expecting any day the arrival of a letter containing money for his school tuition fees from his parents.

The day of payment arrives, however, without any money appearing in the post. Grandma’s illness cuts back her earning ability as a rag gatherer, collecting and selling people’s cast-offs. Embarrassed at not having money to pay his fees, Young-dal stops attending school. Rent arrears and an unsympathetic landlord exacerbate the situation. The eventual happy ending features Han Kim and Moon Ye-bon as the returning parents. Yet the sole Japanese character being cast as a model of kindness and virtue under the occupation really doesn’t ring true.

In Military Train (Suh Kwang-je, 1938) Young-sim (Moon Ye-bong again) has been sold into prostitution. Her concerned boyfriend Won-jin (Dok Eun-ki) thinks he’s found a way to extricate her from her plight via enemy spy Jang (Moon Dong-il) who wants to obtain secret troop train transport timetables. Won-jin’s best friend is Young-sim’s engine driver brother Jum Yong (Wang Pyoung) who is assigned to troop transport trains. So Won-jin tries to extract/steal the information from him.

In Military Train (Suh Kwang-je, 1938) Young-sim (Moon Ye-bong again) has been sold into prostitution. Her concerned boyfriend Won-jin (Dok Eun-ki) thinks he’s found a way to extricate her from her plight via enemy spy Jang (Moon Dong-il) who wants to obtain secret troop train transport timetables. Won-jin’s best friend is Young-sim’s engine driver brother Jum Yong (Wang Pyoung) who is assigned to troop transport trains. So Won-jin tries to extract/steal the information from him.

The combination of a focus on Won-jin’s existential dilemma between betraying his friend and saving his girl, combined with the considerable onscreen presence of period steam locomotives and rolling stock would make this a great first half of a double bill with Jean Renoir’s French classic La Bête Humaine (1938). The surprisingly gripping whole rattles along at a good pace although lines like “my soul will guard the railroad for the Japanese Army” have the whiff of propaganda about them.

Early Korean Cinema: Lost Films From The Japanese Occupation Period runs 7th-28th February at BFI Southbank and the Korean Cultural Centre UK (KCCUK).

Leave a Reply