Of Flesh and Blood

August 12, 2019 · 0 comments

By Jeremy Clarke.

In the West, Hirokazu Koreeda remains Japan’s highest-profile, living, live-action film director. Shoplifters (2018) picked up over eighty awards nominations this year including the Best Foreign-Language Picture Golden Globe and Oscar. A Blu-ray box set of four key films, each with a new commentary, plus some excellent extras and a useful book of critical essays, follows London’s recent BFI Southbank retrospective.

In the West, Hirokazu Koreeda remains Japan’s highest-profile, living, live-action film director. Shoplifters (2018) picked up over eighty awards nominations this year including the Best Foreign-Language Picture Golden Globe and Oscar. A Blu-ray box set of four key films, each with a new commentary, plus some excellent extras and a useful book of critical essays, follows London’s recent BFI Southbank retrospective.

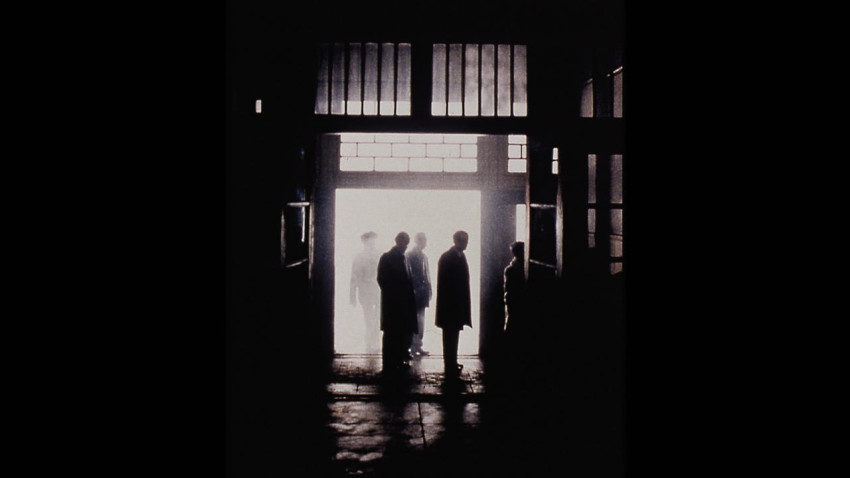

His cinema directorial debut Maborosi (1995) is the only feature Koreeda didn’t also write or edit. Seemingly contented Ikuo (a pre-stardom Asano Tadanobu) goes out one night and is run over by a train. After his young wife Yumiko (Makiko Esumi in her debut role) moves to the North coast to remarry, Ikuo’s suicide continues to trouble her.

Jasper Sharp’s informative commentary explores Maborosi’s specific and Koreeda’s general themes including memory, bereavement, locations, subjectivity, the spirit of place, light and shadow, the passing of time and, perhaps most significantly, family. The films are contextualised within both Japan’s film industry and its wider culture locating this director alongside others who emerged in the mid-nineties such as the young and hip Shunji Iwai, “V-Cinema” (straight-to-video) practitioners Shinji Aoyama, Kiyoshi Kurosawa and Hideo Nakata and fellow former documentarian Naomi Kawase. Their films conveyed a sense of loss, sometimes for a family member. Kicking off the Heisei era (1989-2019) under Emperor Akihito, they signalled the rejuvenation of Japanese cinema when it was on its last legs.

The half-hour extra Birthplace (2003) sees Esumi revisit several locations from the film eight years later. She heads for the film’s waterside house, now abandoned and filled with junk. Her own father died at age 36 some 13 years before the shoot and in some scenes she was thinking about him rather than acting. You suspect some of that found its way into her performance.

After being rebuked by his idol Taiwanese director Hou Hsiao-Hsien for planning Maborosi so meticulously that the shooting process left him no room for discovery, Koreeda fell back on his TV documentary roots, interviewing 500 ordinary people about their most important memory if they could take only one with them to heaven. He incorporated ten into After Life (1998), playing recently deceased clients in the care of petty bureaucrats played by professional actors. They are given one week to choose and recreate that memory on film before being sent off to the next place.

After being rebuked by his idol Taiwanese director Hou Hsiao-Hsien for planning Maborosi so meticulously that the shooting process left him no room for discovery, Koreeda fell back on his TV documentary roots, interviewing 500 ordinary people about their most important memory if they could take only one with them to heaven. He incorporated ten into After Life (1998), playing recently deceased clients in the care of petty bureaucrats played by professional actors. They are given one week to choose and recreate that memory on film before being sent off to the next place.

One extra sees bureaucrat cast member Arata ruminate on watching meteor showers from rooftops. Another extra comprises sixteen minutes’ worth of deleted scenes run together in chronological order like an alternative version of the movie. It’s instructive to see what Koreeda cut out: chiefly much of Mr. Shoda’s (Toru Yuri) interview material detailing sexual experiences.

Bristol Watershed programmer and sometime critic Tara Judah’s commentary positions the film in ‘liminal space’, as a work about a threshold between worlds or states. The influence of Koreeda’s documentary work in particular Without Memory (1996) is discussed. Noting that his grandfather suffered from Alzheimer’s disease, she cites the blow-up doll protagonist of Air Doll (2009 who starts out with no memory but subsequently learns about humanity from a video store. After Life’s Japanese title, Wonderful Life, invokes the classic James Stewart vehicle It’s A Wonderful Life (1946), wherein his suicidal character revisits his own history to see the positive difference he’s made to other people’s lives. Mochizuki (Arata) has a similar experience.

Jasper Sharp’s onstage 2013 BFI Southbank interview about Like Father Like Son (2013) contrasts it with the earlier Nobody Knows (2004) as two sides of the same coin, too much parental control versus none at all. Koreeda discusses his process for working with children. They get no script, rather an explanation of the coming scene which he builds up via improvisation and the children’s own words. Nobody Knows covers four pre-teenage children abandoned by their mother and left to fend for themselves in their Tokyo apartment. This work of fiction is based on 1988’s real-life Sugamo child abandonment case. Koreeda’s first film with kids is also his first family drama. Twelve year old lead Yagira Yuya won best actor at Cannes and would go on to a career including Destruction Babies (2016).

Extras include an insubstantial seven-minute behind-the-scenes featurette and a fascinating commentary by Japanese-Australian film-maker, writer and academic Kenta McGrath, who commendably focuses on what you’re seeing on screen. McGrath discusses Koreeda’s uncharacteristic use of close-ups and significant objects such as a jar of red nail varnish indelibly staining the floor, linking the eldest daughter to her initially present and later absent mother. Japan’s answer to a corner shop, the combini, also proves significant. McGrath really gets to the nitty-gritty of Koreeda’s film-making process.

Still Walking (2008) is a more conventional if highly personal family drama taking place within 24 hours as Ryota (Abe Hiroshi), his wife and stepson visit his ageing parents Toshiko and Kyohei (Kirin Kiki and Yoshio Harada). Ryota is their second son, placed in the role of the first following the death of his older sibling Junpei many years before, something with which his parents have never fully come to terms.

A fascinating half-hour Making Of shows the director constantly vanishing off-set to explore and find elements to add such as a crepe myrtle in bloom in a nearby garden (coincidentally, the same flower was a major feature of Keiichi Hara’s Miss Hokusai). Koreeda explains the film is shot through with personal details of his mother. He and his crew painstakingly reconstruct her home cooking in the form of corn tempura (corn as in corn-on-the-cob) while Kirin Kiki tries to make the dresses his mother wore work on the screen by adding simple lace ruffs to the necks.

There’s more about Koreeda’s mother in the 2019 BFI Southbank interview with Michael Leader. As a child Koreeda used to watch Japanese-dubbed Vivien Leigh and Joan Fontaine movies with her, which she would ruin with spoilers. He also talks about his friendship with the late Kirin Kiki, for whom he wrote six films, not to mention many others which she turned down or for which she even recommended other actors. A fairly sparse commentary by Alexander Jacoby explores stylistic similarities with the work of classic director Yasujiro Ozu as well as the onscreen use of food and the stable of actors common to many Koreeda films. A nice little stills gallery completes the package.

Note: The romanised form of his name is sometimes spelled with a hyphen as in Kore-eda and sometimes spelled without. The recent BFI season and the current Blu-ray release have opted for the non-hyphenated spelling, so that one has been used here.

Of Flesh And Blood – The Cinema Of Hirokazu Koreeda is released on BFI Blu-ray on 12th August 2019.

Leave a Reply